Hospitals and other health care providers need flexibility to respond rapidly to a looming health crisis. The spread of the COVID-19 virus could cause a shortage of beds in Illinois hospitals if projections of the infection rate come true.

But antiquated state regulations could get in the way.

Before expanding bed capacity, Illinois hospitals normally require approval from the state by obtaining a “certificate of need,” or CON, after completing a lengthy process to demonstrate that new beds are necessary.

Fortunately, the Illinois Emergency Management Agency Act grants Gov. J.B. Pritzker emergency powers to suspend any provisions of a regulatory statute that would prevent, hinder, or delay necessary action by the state or state agencies. Pritzker has the power under the act to suspend the CON law in the event of a public health emergency. The governor already announced plans to convert Chicago’s McCormick Place convention center into a 3,000-bed field hospital for COVID-19 patients by April 24. But suspending CON laws formally would give hospitals around the state the flexibility to expand capacity without waiting for government approval.

By suspending the CON law to give hospitals throughout the state the ability to immediately add bed capacity and other necessary infrastructure, Pritzker would be following the lead of North Carolina, which temporarily lifted one of the more restrictive CON laws to meet the pandemic.

Illinois should suspend its law, then make a full repeal.

CON laws could stand in the way of smart responses to future health crises. And they fail to achieve their basic objectives – lowering health care costs while simultaneously improving the quality of health care. In fact, researchers in 2011 found Illinois would have had 87 additional hospitals and 20 additional ambulatory care centers if not for this antiquated system.

COVID-19 patients are projected to overwhelm Illinois hospitals

According to the Harvard Global Health Institute, or HGHI, a best-case scenario based on mathematical models would see 20% of Illinois’ adult population, or almost 2 million people, becoming infected with the novel coronavirus, which would overwhelm the state’s hospitals.

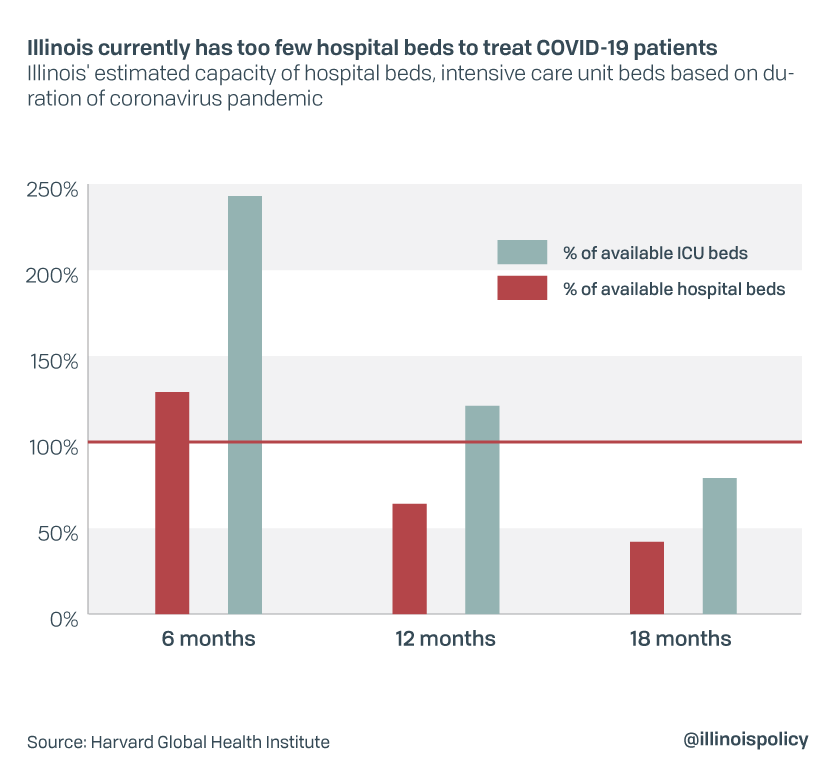

According to HGHI, if close to 2 million people become infected, 400,000, or 20%, could require hospitalization and over 88,000, or 4%, could require treatment in an intensive care unit, or ICU. As of March 24, 16% of infected patients had required hospitalization and 4% required ICU care, according to the Chicago Tribune. The HGHI study does not include the newly announced 3,000 new beds planned for the McCormick Place field hospital, but it demonstrates how severely a rush of coronavirus cases would stress Illinois’ hospital capacity if this number of infections occurred within six months or were spread out over 12 months or 18 months.

Illinois has 30,006 total hospital beds, according to HGHI, exclusive of the 3,000 new beds planned for the McCormick Place field hospital. If all COVID-19 infections occurred within six months, the state would need 27,409 beds to adequately treat all patients. Comparing HGHI projections to Illinois Department of Public Health, or IDPH, statistics as of March 23, the state would have the following needs.

Non-ICU bed needs:

- Illinois has 12,588 non-ICU beds available as of March 23, according to IDPH.

- HGHI estimates that Illinois could potentially have 21,293 beds available, but only if the occupancy rate for non-COVID-19 patients was reduced by 50%.

- If all COVID-19 infections occur within six months, the number of non-ICU beds needed, according to HGHI, is 129% of beds potentially available.

- If COVID-19 hospitalizations are spread over 18 months they would require 42% of Illinois’ potential bed capacity.

- Illinois has 1,106 ICU beds available as of March 23, according to IDPH.

- HGHI estimates that Illinois could only have 2,418 ICU beds potentially available but would need 5,875, or 243% of potential ICU bed capacity, if all COVID-19 infections occur within six months.

- If infections occur over 18 months, they would still require 79% of potential ICU capacity.

If an Illinois hospital wants to increase its bed capacity by 20 beds or 10%, whichever is less, over a two-year period, Illinois’ CON law requires approval from the Health Facilities and Services Review Board. This law is scheduled for repeal on Dec. 31, 2029.

Based on the potential number of COVID-19 patients, any sufficient increase in bed capacity would require board approval. The restrictions on bed capacity also apply to recategorizing beds for a different purpose and relocating of beds from one location to another, even if there is no net increase in total bed capacity. That deprives hospitals of much-needed flexibility to respond to rapidly changing needs of patients and the community at large.

The CON law also requires approval from the board before the construction or modification of any health care facility, including hospitals. This applies to capital expenditures, including diagnostic and therapeutic equipment, that meet the following cost thresholds:

- $13,743,450 for hospitals

- $7,768,030 for long-term care facilities

- $3,585,250 for all other facilities

History of Certificate of Need

CON laws became popular in the 1970s as a way to simultaneously improve quality of care, by limiting the number of providers available to perform certain procedures and allowing providers to specialize and improve service quality, and limit the growth in health care spending.

Illinois’ CON law was enacted in 1974 after the federal government passed the National Health Planning and Resources Act that encouraged the adoption of CON laws nationwide, according to the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. The federal government withheld funding from states that failed to adopt CON laws.

According to Mercatus, the goals of the federal legislation were to ensure or encourage an adequate supply of health care services at lower cost and higher quality, to increase access in rural areas, provide more charity care, and encourage use of low-cost alternatives such as ambulatory care.

However, research showed CON laws were failing to achieve these goals, and Congress repealed the federal law in the mid-1980s. Subsequently, 15 states representing 40% of the U.S. population repealed their own CON laws, but not Illinois.

CON laws have failed to achieve their objectives and may have done more harm than good

CON laws like those in Illinois have failed to serve their purpose. They were supposed to increase the quality of health care by limiting the number of providers of certain procedures, according to a 2017 Mercatus Centerpaper, thereby allowing practitioners to specialize and improve service quality. Mercatus found instead that:

- CON programs restrict the supply of health care services they regulate, which can lead to an increase in per unit costs and a reduction in quality, according to economic theory.

- The weight of evidence suggests that CON laws are associated with higher levels of spending.

The Mercatus Center concluded that:

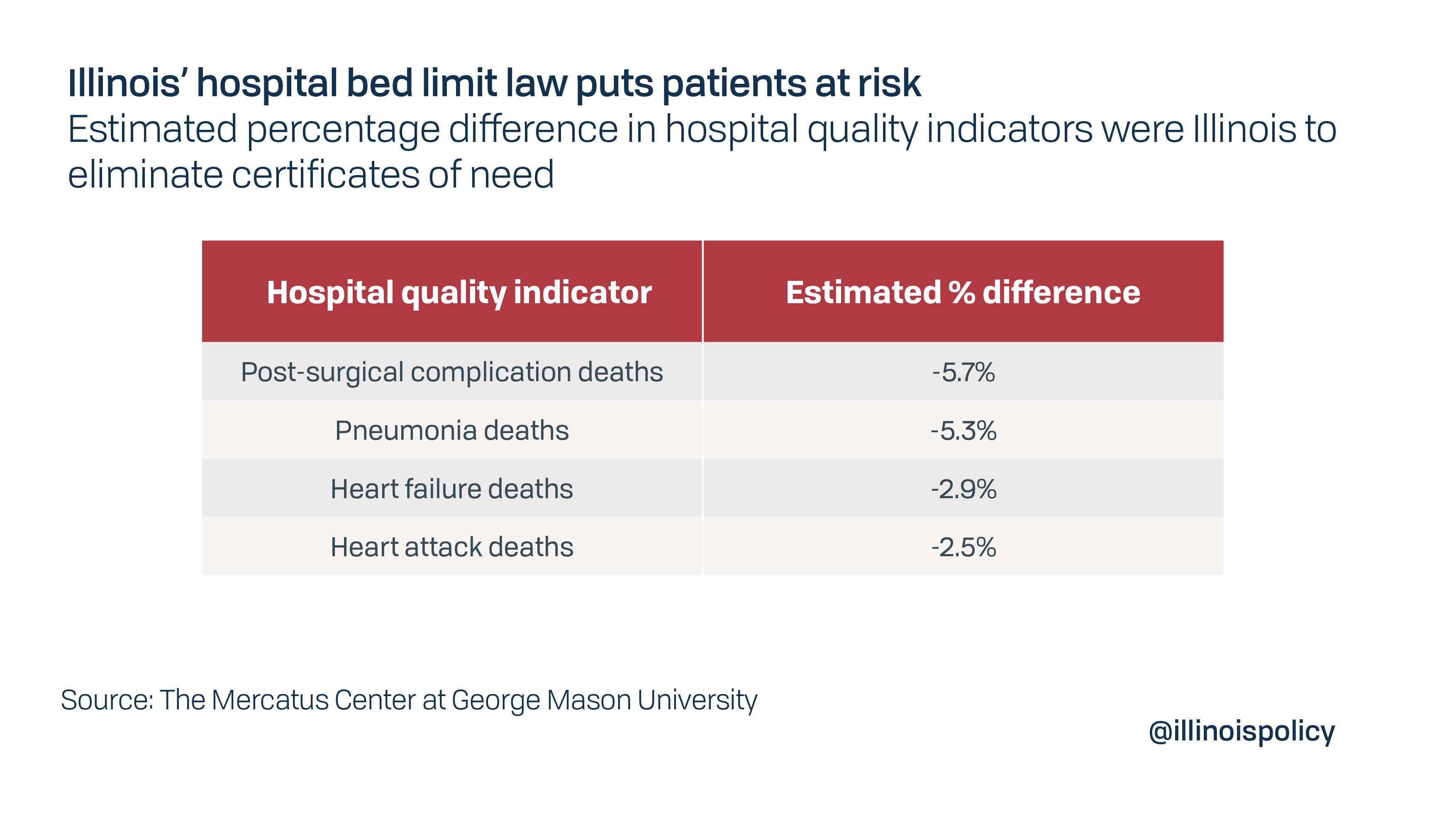

- There is no evidence that quality of care at hospitals in CON states is better than in non-CON states.

- Hospitals in CON states performed worse than those in non-CON states on eight of nine indicators in the study.

- The average 30-day mortality rate for patients discharged with pneumonia, heart failure and heart attack in CON states was 2.5 to 5% higher than hospitals in non-CON states.

In September 2008, representatives of the Federal Trade Commission and the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice delivered a joint statement to the Illinois Task Force on Health Planning Reform. The statement summarized the agencies’ experience investigating and litigating antitrust cases in health care markets across the country, plus the results of numerous hearings on competition and policy concerns in the health care industry. Among their key findings:

- Certificate of need laws impede efficient performance of health care markets.

- The methodologies used to pay health care providers in the 1970s that may have justified CON laws have significantly changed.

- On balance, CON requirements have no effect or can actually increase per capita spending, including hospital spending.

The CON process is also susceptible to corruption. In 2004, a member of the Illinois Health Facilities Planning Board was convicted for accepting a kickback from a construction company in exchange for approving a CON application.

Nonetheless, Illinois failed to repeal its CON law.

Illinois should repeal its CON law

CON laws were supposed to improve the quality of health care while controlling the growth of health care costs. Studies have shown that they accomplished neither and have had the opposite effect.

The COVID-19 crisis threatens to overwhelm Illinois hospitals that have an insufficient number of regular and ICU beds available to treat patients. The inability of hospitals to respond rapidly could put patients at risk.

Illinois’ CON law has not worked as planned. The COVID-19 crisis mandates suspending it, and the need for a more flexible, better-functioning health care system demands a permanent repeal.