What will Illinois look like when the state’s controversial criminal justice reform bill called the SAFE-T Act is fully implemented January 1?

Look to Cook County, which has already crippled its criminal justice system with changes similar to those in the SAFE-T Act.

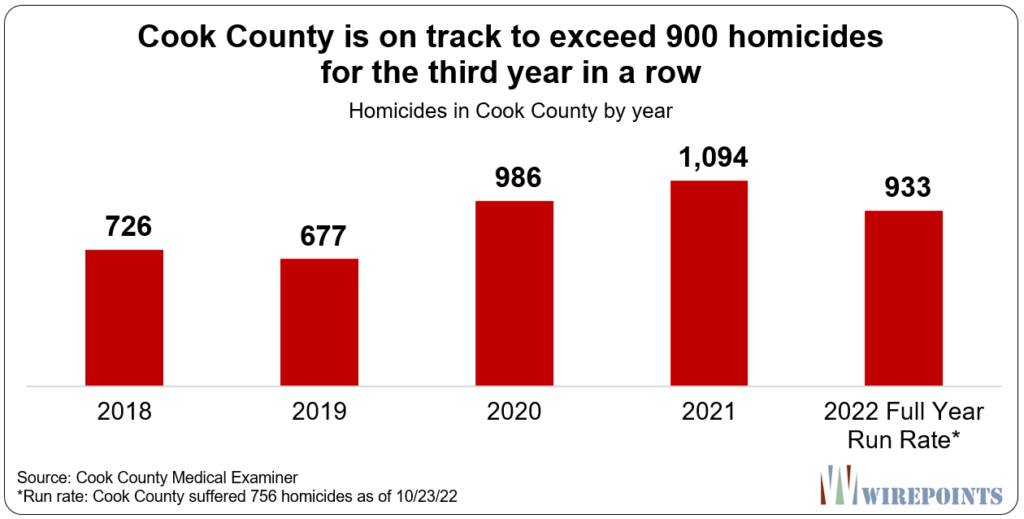

Too often there, dangerous pretrial detainees set free on low-cash or no-cash bail roam the county and shoot, kill, carjack, rob, burgle, and commit sundry other crimes. Meanwhile the county is on track to exceed 900 homicides for the third year in a row.

Three big mistakes have degraded public safety in Cook County: misuse of bail reform, over-reliance on electronic monitoring, and defining down crime. Now thanks to specific provisions of the SAFE-T Act, the State of Illinois is poised to replicate much of what has gone wrong in Cook County.

The bad results of bail “reform”

Cook County Chief Judge Timothy Evans instituted bail reform in September 2017 to reduce pretrial detention of low-income defendants who couldn’t afford cash bail. His goal was for bail to be used only when completely necessary, and even then in the least possible amount.

The harm done by that approach is clear. There’s been a growing parade of pretrial defendants out on bond but then charged with new crimes. Add to that: far fewer defendants are showing up for court, and even fewer defendants are being detained before trial.

Quarterly reports from Evans’ office show that by halfway through 2020 nearly 9,500 defendants released before trial had been charged with new offenses. By mid-2022 that number had grown to 15,086. That was 18 percent of defendants set loose before trial.

Of those 15,000-plus alleged crimes by pretrial defendants freed from late 2017 through mid-2022, 2,841 were classified as violent offenses, or “person offenses” such as battery, assault, or child neglect. Another 1,594 crimes were weapons offenses.

Other outcomes are also alarming. Evans’ data shows that by mid-2022, 20 percent of bond court defendants who were granted pretrial freedom from detention failed to appear at subsequent court dates. That rate was much worse than the 9 percent court appearance failure rate after bail reform’s first quarter in late 2017.

Additionally, the percentage of defendants ordered held without cash bail shrank to 4.4 percent of the total by mid-2022 from 8.5 percent in mid-2019.

The bottom line: the Cook County revolving door let too many risky pretrial suspects pass through before facing justice and they went on to earn new charges 4,435 times for violent, “person” or weapons offenses. Including shootings, murders, attempted murders, and criminal sexual assault.

Horror stories tied to the failure of bail reform in Cook County are common.

- A man was released by Cook County courts to electronic monitoring for a gun store burglary and then released from monitoring before being charged with fatally stabbing a drugstore clerk.

- A defendant out on bond before trial for attempted murder was then charged with killing two at a video shoot party.

- A five-time felon out on bond for two weapons charges was then charged with killing two at a house party on the West Side.

- Members of a carjacking crew, including charged suspects out on bond for repeated offenses, were then charged in the killing of a retired firefighter in a South Side carjacking attempt.

- A serial carjacker free on bond killed a young father in Chinatown in a failed carjacking attempt.

- A 17-year-old out on bond before trial on felony gun charges then allegedly carjacked an SUV and slammed into another vehicle, killing 55-year-old Dominga Flores.

- Another defendant out on bail on a felony gun charge was arrested for murdering a man in a gang-related shooting.

- An 18-year-old out on bond for three weapons charges, plus theft and carjacking, was charged with first-degree murder and armed robbery after shooting a Hyde Park bartender walking home after work.

The numbers are lowballed

Yet it’s worse than all that, because the full scope of the bail reform problem is actually unknown.

The 15,000 total crimes – and almost 3,000 violent or “person” crimes – charged to defendants released before trial under Cook County bail reform since late 2017 are likely lowballed. There are two reasons.

First, Evans was found to have jimmied the numbers down dramatically in 2020 by not counting certain types of important new crimes by defendants out on bail.

Second, arrest rates in Chicago are paltry, 12 percent for all crimes last year and 6 percent for major “Index” crimes. Most offenders aren’t even getting caught. The count of Cook County defendants free on bail, but committing new crimes before trial, can’t be accurately known if the vast majority of reported crimes never even result in arrest.

Former 43rd Ward Chicago Alderman Michelle Smith accented the key role of both uncounted crimes by bond court defendants and miniscule arrest rates in a recent letter. Smith – who was a Democratic Committeeman in her ward – urged supporters to reject claims that bail reform works, and to vote against retaining Evans as a circuit court judge.

But the movement is in the opposite direction. Illinois will soon follow the lead of Cook County. Come January 1, pretrial detention of new defendants will be sharply limited and cash bail will be abolished statewide under the Illinois SAFE-T Act.

What’s alarming is how much further the SAFE-T Act goes. Even Cook County officials admit they’ll have to let more defendants out on January 1 and are scrambling to petition judges to keep some of them behind bars.

Imposing electronic monitoring worst-practices

As fewer defendants were being detained because of Cook County’s reduced use of cash bail, judges began to add to the ranks of the county’s electronic monitoring (EM) programs. The pretense of requiring electronic monitoring provided political cover as more and more emphasis was put on turning defendants loose before trial. As a result, defendants on EM charged with violent or weapons crimes grew from 49 percent of the total Cook County EM population in mid-2018 to 76 percent by mid-2022.

Dissent to this risky practice came even from within Cook County’s government. Cook County Sheriff Thomas Dart earlier this year and in 2020 warned other officials that too many charged murderers were being released before trial to electronic monitoring. He also voiced concern this year that three quarters of EM defendants let go before trial were charged with violent or weapons crimes.

The resulting mayhem has been too extensive to fully catalog here, but consider these telling failures of electronic monitoring in Cook County.

- A scofflaw EM defendant recently tried to steal a vehicle in Chicago that had been left running. The owner latched onto the roof and hung on a wild ride until the driver was seen fleeing while still wearing his ankle bracelet.

- A man at large on bond for three pending weapons charges and for escaping electronic monitoring, was finally taken into custody on a new weapons charge and put by a Cook County judge on…..electronic monitoring. Again. Of course he should have been home-bound on EM but – imagine this – was instead charged with fatally shooting a woman at a block party.

- A man with four prior felony convictions and a new charge for a shooting was out on bond and on electronic monitoring, and then was charged with killing a relative’s boyfriend.

- A woman out on bond for attempted murder of a police officer was charged with escaping from electronic monitoring last year – and then again last week. The ankle bracelet died this last time around so that’s not indicative of ill intent. But the question arises: how is she even out on bond to begin with, considering the charge?

- Then there was the EM defendant out on bond before trial in a felony weapons case who admitted to threatening a judge via Zoom chat during a hearing. He was charged with threatening a public official and finally held without bond.

Once again, state lawmakers seem intent on taking the worst practices of Cook County one step further, through the SAFE-T Act. It gives EM defendants 48 hours to be missing before authorities can declare them noncompliant and pursue them. Plenty of time to intimidate or harm a victim or other witness. Plenty of time to flee. No matter.

SAFE-T also gives EM defendants eight-hour breaks from monitoring twice weekly for personal business known as “essential movement.” By April of this year, some two dozen EM defendants in Cook County had been arrested for alleged crimes committed while on those special breaks. Charges included weapons and drug offenses, serial shoplifting, and armed robbery.

State law mandating 48 hours free roaming for EM scofflaws and 16 hours of free time-off weekly for EM defendants – most of them already facing weapons or violent crime charges – cannot possibly be in the public interest. Or the interests of witnesses who may be intimidated or harmed by them while defendants are unmonitored.

Defining crime down

Cook County has lost its focus on public safety not just because bail reform and electronic monitoring have gone wrong. The sweeping dysfunction in criminal justice also results from mismanagement by Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx. She has defined crime down.

State law sets the bar for felony theft at $300. But in Cook County, Foxx raised it to $1,000. This has emboldened retail thieves who now operate in teams so each member can steal just under the limit. Several busts have shown that the retail theft rings plaguing downtown Chicago and suburban mall retailers are part of organized criminal enterprises.

And consistent with a 2011 ordinance approved by Cook County Board members and Board President Toni Preckwinkle, Foxx has not prosecuted immigration scofflaws. Millions of Chicagoland immigrants have played by the rules but Cook County welcomes those who don’t with no consequences.

In addition, Foxx has increasingly sidestepped prosecution of violent criminals. It is couched in the language of protecting defendants from ill-supported prosecutions. That’s a worthy goal but many of the cases give pause.

Some examples: After Chicago Police arrested a man for a barbershop murder and presented strong evidence, Foxx’s office declined to prosecute until the same man was charged anew in an October 2022 triple shooting.

Her office declined to prosecute any of the three men charged by police for starting a Near West Side shootout in August despite supporting statements from a witness and video evidence. And Foxx’s office also declined to prosecute charged suspects in a fatal Schaumburg stabbing and a Chicago West Side shootout.

The message: crime pays.

The SAFE-T Act also finds ways to cut breaks to alleged criminals charged with serious crimes, again taking a page from Cook County’s botched experiment in criminal justice. For example, it has defined down what constitutes first-degree murder. Previously, if you started a shootout that directly led to fatalities, you could have been charged with murder. Not anymore. At least twice now in Chicago men who started shootouts that ended with people dead – in December of last year and again on January 1 of this year – have escaped murder charges as a result.

The Act also cuts slack to court-date no-shows. Previously, an arrest warrant would be issued for a no-show’s arrest after missing an initial court date. Now, they just get a toothless “notice to appear.”

In addition, under SAFE-T, pretrial detention requires proof by prosecutors of “willful intent to flee,” but a past failure to appear for another court date cannot be used as evidence of that risk.

It’s as if defense attorneys rewrote the statewide rules for prosecution – Cook County defense attorneys.

Bad policy hastens prosecutors, cops to quit

Cook County’s Chief Judge and State’s Attorney together have presided over sharp growth in crimes by defendants released before trial, an increasingly high-risk population on electronic monitoring and a stark defining down of crime. One result is increasingly demoralized prosecutors who are quitting in droves.

But it’s not just Cook County prosecutors who are voting with their feet against bad policy that undercuts those charged with enforcing public safety. It’s also police statewide, reacting to the Illinois SAFE-T Act.

The legislation makes state decertification complaints against cops anonymous and deep-sixes required sworn affidavits for local misconduct complaints. It creates a statewide database to promote decertification probes of police but requires no disclosure of sentencing decisions by judges and prosecutors which may erode public safety badly.

The Illinois Association of the Chiefs of Police reports that based on surveys completed by 239 Illinois departments, officer resignations jumped 65 percent in 2021 versus 2020. The SAFE-T Act was finalized in early 2021.

You can’t fool prosecutors and you can’t fool cops. Since the passage of the SAFE-T Act, the traditional criminal justice ethos has been flipped upside down.

A crime-filled future

As the statewide abolition of cash bail takes effect January 1, what will be the net effect of the SAFE-T Act? It won’t just be the harm from provisions reflecting misguided policies already unfolding in Cook County. It will also be a growing sense of public disorder, unease, and lawlessness.

More and more in Chicagoland come reports of targeted victims engaging in armed self-defense. Chicago neighborhoods continue to hire unarmed private security forces. How far a step is it for those who are more well-off to employ legally-armed guards like politicians do, while the rest of us are left to fend for ourselves? Where exactly it will all end isn’t clear.

Yet if Illinois does not get a firmer grip on criminal justice, the state may be irreparably damaged. The responsibility will sit squarely on the shoulders of state legislators – and the engineers of chaos in Cook County.