An indictment of Illinois’ education system

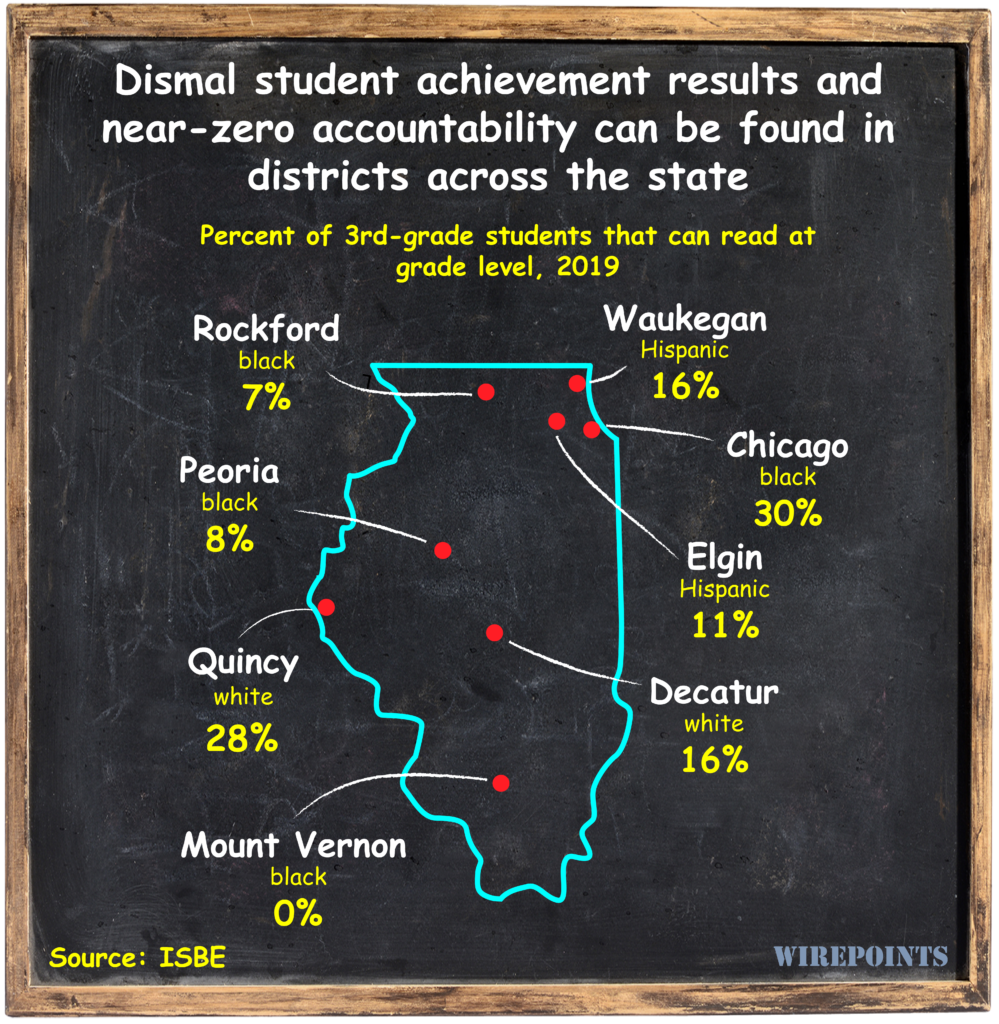

If what follows isn’t an indictment of Illinois’ education establishment, we don’t know what is. Of Decatur’s public school 3rd-graders in 2019, just 2 percent of black and 16 percent of white students could read at grade level. In Rockford, it was 7 percent of black students. In Peoria, 8 percent of blacks. And in Elgin, just 11 percent of Hispanic 3rd-graders could read at grade level. Similar results can be found across the state.

The data Wirepoints presents in this report represents an absolute dereliction of duty by those who run Illinois’ public schools. It’s not about money, it’s not about race, it’s not about curriculum and it’s not about critical race theory. It’s about a system that fails at its most basic function: to prepare Illinois children for their future.

Our assessment is harsh because student outcomes are beyond dismal and no one, it seems, takes any responsibility for them. Social promotion, hyper-inflated teacher evaluations and misleading “accountability” designations from the Illinois State Board of Education all help to deflect blame.

We’re also harsh because nobody in the system wants to upset the apple cart. The rewards are just too lucrative. The Illinois Constitution and multi-year labor contracts guarantee job security, big salaries and even bigger pensions for those in education. The sprawling district bureaucracy provides thousands of administrative jobs. Not to mention the back-scratching relationship between unions and lawmakers that protects the status quo.

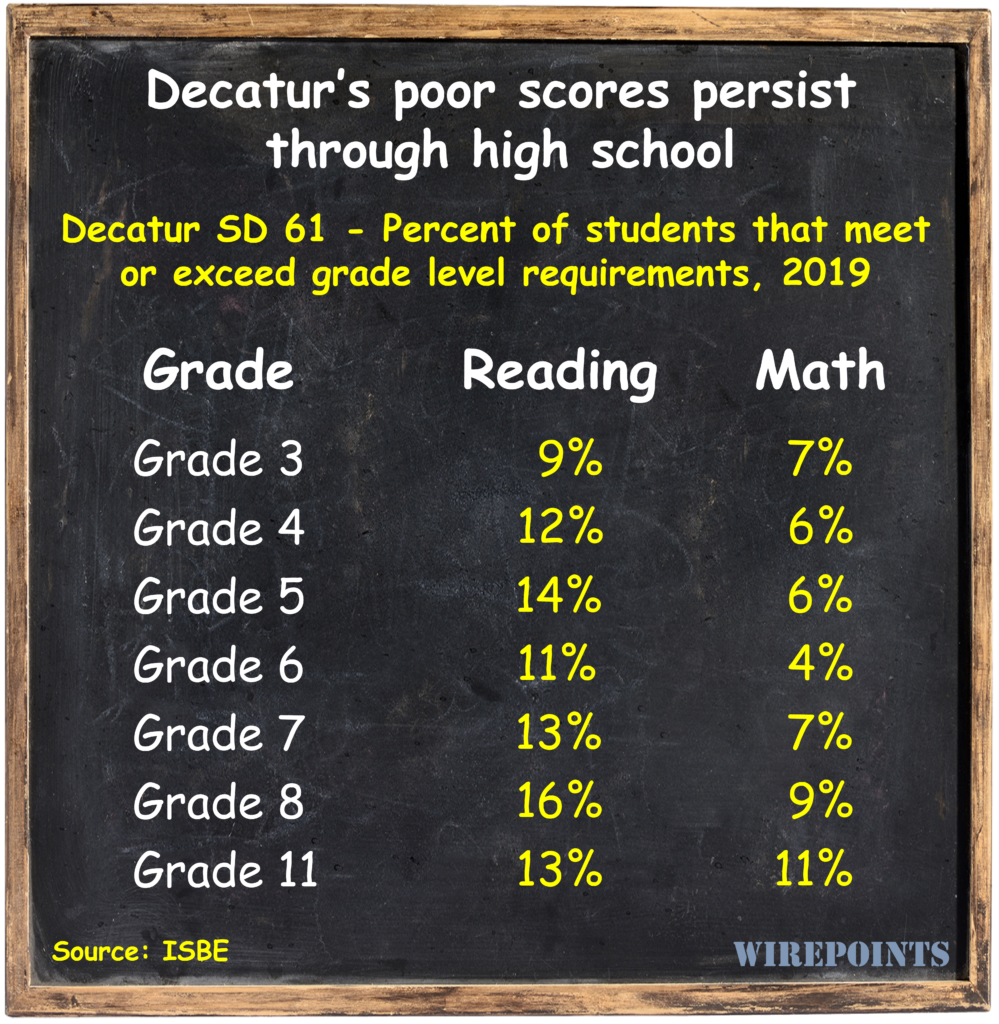

This report focuses on Decatur School District 61 because it’s arguably the poster child for the education system’s failures. Just 9 percent of Decatur’s 3rd-grade students can read at grade level. And every year the district graduates hundreds of students who are grossly unprepared for either college or a career.

The same story could be written about the students of Rockford, Waukegan, Peoria, Quincy, Chicago or any one of a hundred Illinois cities. The only difference is in the degree of failure.

The same story could be written about the students of Rockford, Waukegan, Peoria, Quincy, Chicago or any one of a hundred Illinois cities. The only difference is in the degree of failure.

For sure, plenty of Illinois’ 860 school districts achieved better student outcomes in 2019. But a cursory glance at state report card data shows higher performers were the minority. Just 89 districts had at least 60 percent of students who could read at grade level. In 168 districts, by comparison, less than 25 percent of students could read at grade level.

Overall, less than 40 percent of all students in Illinois were proficient in either reading or math (see Appendix for details).

Who is it that’s allowing such bad outcomes to persist without intervention? Administrators? School boards? The Illinois State Board of Education? State lawmakers? And where are the parents in all this? Does anybody care?

Below we look at Decatur’s failed results and how parents are misled by district and state statistics. We also highlight the poor results of other major districts across the state. Last, we examine the “underfunding” myth and how Illinois’ education system perpetuates itself despite its failures. It’s important to note that Wirepoints focused on 2019 achievement data to avoid the noise the pandemic had on student outcomes in 2020 and 2021. School closures, remote learning, masks and more have had a significant negative impact on outcomes that will take years to unpack.

The failures of Decatur SD 61

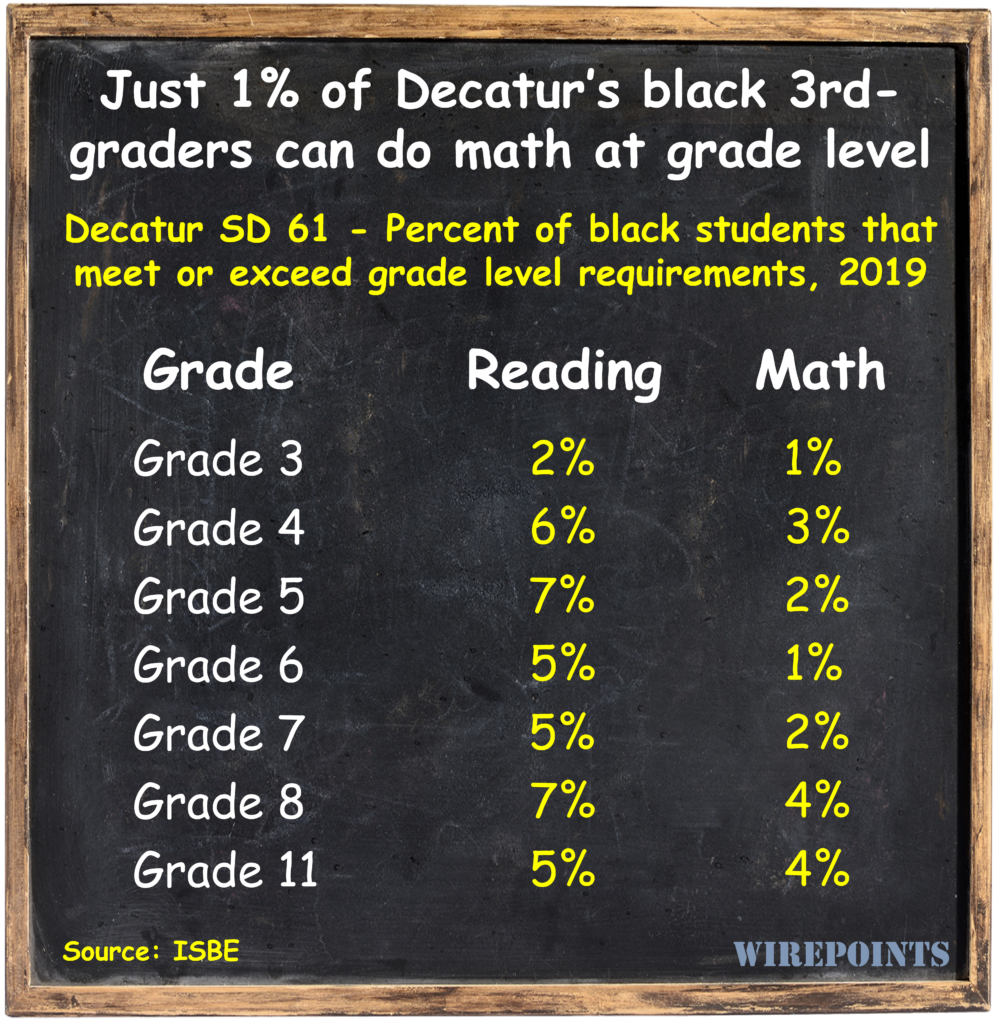

When Wirepoints first came across the pre-pandemic 3rd-grade reading scores of Decatur Public Schools last year, we thought they’d been misreported. The State Board of Education’s Report Card said just 2 percent of Decatur’s black 3rd-graders met or exceeded reading requirements in 2019. Just 2 percent?

When we clicked over to the math results, they were worse. Only 1 percent of Decatur’s black 3rd-graders could do math at grade level. We didn’t believe the results could be so dire, but the bad numbers persisted all the way through high school, where only 5 percent of black 11th-graders met reading standards.

About 8,400 kids go to Decatur Public Schools and half of them are black, so if there’s no change in the next decade more than 3,000 black students will enter the workforce ill-prepared – or worse. And before anyone lays the blame on “white supremacy” and “systemic racism,” know that it’s not much better for Decatur’s white kids, who make up more than a third of the district’s enrollment.

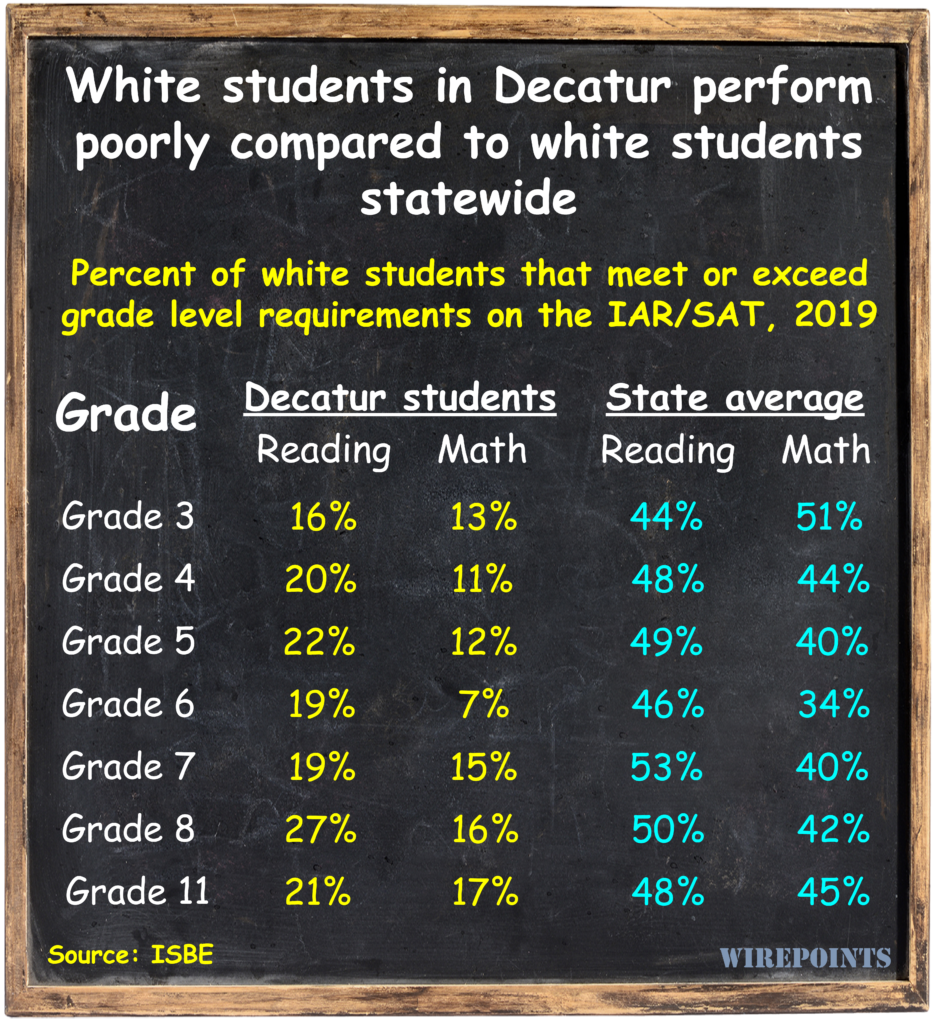

Just 16 percent of white 3rd-graders were reading at grade level in 2019. That outcome is far lower than the 44 percent statewide average for whites.

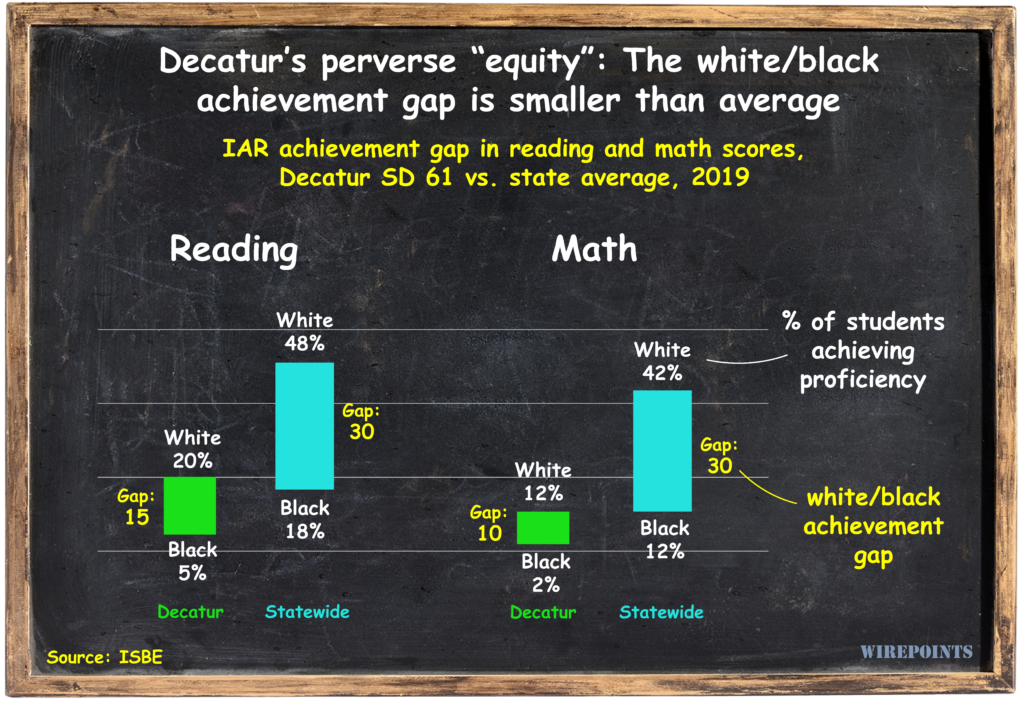

The white scores in Decatur are so low that the district has achieved a perverse form of “equity:” all students, regardless of color, are failing.

The district’s black/white reading achievement gap is only 15 percentage points, half the statewide gap of 30 percentage points. Decatur’s achievement gap for math is even smaller: 10 percentage points versus 30 statewide. Normally, a narrow gap would be cause for celebration. Not so here.

Excuses

Wirepoints went down to Decatur in November 2021 to hear what district officials had to say about their student results. There we met with Jeff Dase, Assistant Superintendent for Teaching and Learning, the district’s new accountability manager, and Denise Swarthout, Chief Communications Officer.

The discussion at first focused on the pandemic and how difficult things had become over the past months. Certainly Decatur, with its large low-income population, was struggling. But Wirepoints’ primary interest lay in understanding why the district’s pre-COVID outcomes were so bad.

Yes, they verified, Decatur’s reading and math numbers were “alarmingly low.”

Many of the district’s problems, we were told, were due to a lack of an established district-wide curriculum in previous years. Individual teachers managed their own lesson plans.

High turnover in the district’s administration was also to blame. Every new administrator instituted their own processes and plans, so no initiative was ever maintained for long.

More skilled teachers are needed, they said. More black teachers, too. Students need more robust incentives. And, of course, the district said it needs more money for higher salaries and more programs.

However, even if all of that were true, it can’t explain why only 2 percent of black students could do math at grade level.

Wirepoints uses the phrase “cannot read or do math at grade level” to describe students who do not meet Illinois Assessment of Readiness (IAR) “proficiency” standards. This is consistent with the Illinois School Board of Education’s definition of proficient: “Students performing at levels 4 and 5 met or exceeded expectations, have demonstrated readiness for the next grade level/course and, ultimately, are likely on track for college and careers. ”We also use the “grade level” definition as shorthand for the 11th-grade Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) proficiency standards.

It’s all a facade

In a system with this much failure it’s easy to fault everyone involved with the

city’s education system, including Decatur’s parents. But before we assign parents their share of the blame, let’s first look at what the education system is selling to the public.

Take a spin through the Illinois Report Card data for Decatur and you’ll find lots of statistics that say children are performing well, along with evaluations that grossly inflate the competence of Decatur’s teachers and schools.

You’ll also find that Decatur students are pushed through elementary and middle school even though no more than 16 percent in any given grade can read or do math at grade level.

“Social promotion” – pushing kids into the next grade regardless of ability – leaves unsuspecting Illinois parents believing their kids are being educated simply because they’re advancing. But it actually leads to higher dropout rates and lower rates of graduation, according to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, crippling students’ future chances for success.

In contrast, states like Florida outlaw social promotion. They require students to stay in 3rd grade until they absolutely have the skills they need to move on to the next grade. (Credit to State Rep. Rita Mayfield for trying to pass a similar bill in Illinois.)

Social promotion in Illinois continues into high school. That’s when district officials tell parents what they want to hear – that their children have what they need to graduate.

In 2019, 70 percent of all Decatur 9th-graders were shown on the state report card to be “on track” to graduate. Never mind that only 9 percent could do math at grade level the year before.

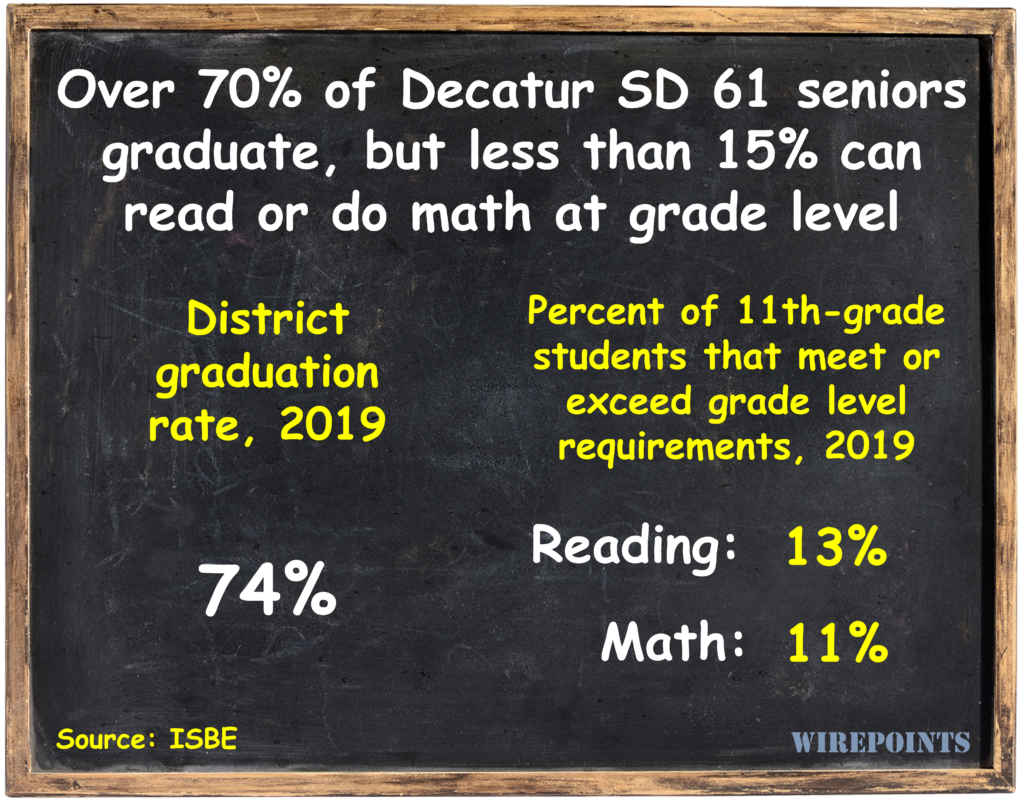

Most Decatur parents also see their children get a diploma, something they’re sure to be proud of. In 2019, 74 percent of Decatur seniors graduated. But that graduation rate is a facade. The district’s 2019 SAT scores show that only 11 percent of 11th-graders were proficient in math and only 13 percent were proficient in reading. Students are being pushed out of the system with no regard for their college or career readiness.

The Illinois State Board of Education is also complicit by selling feel-good numbers on teacher and school quality.

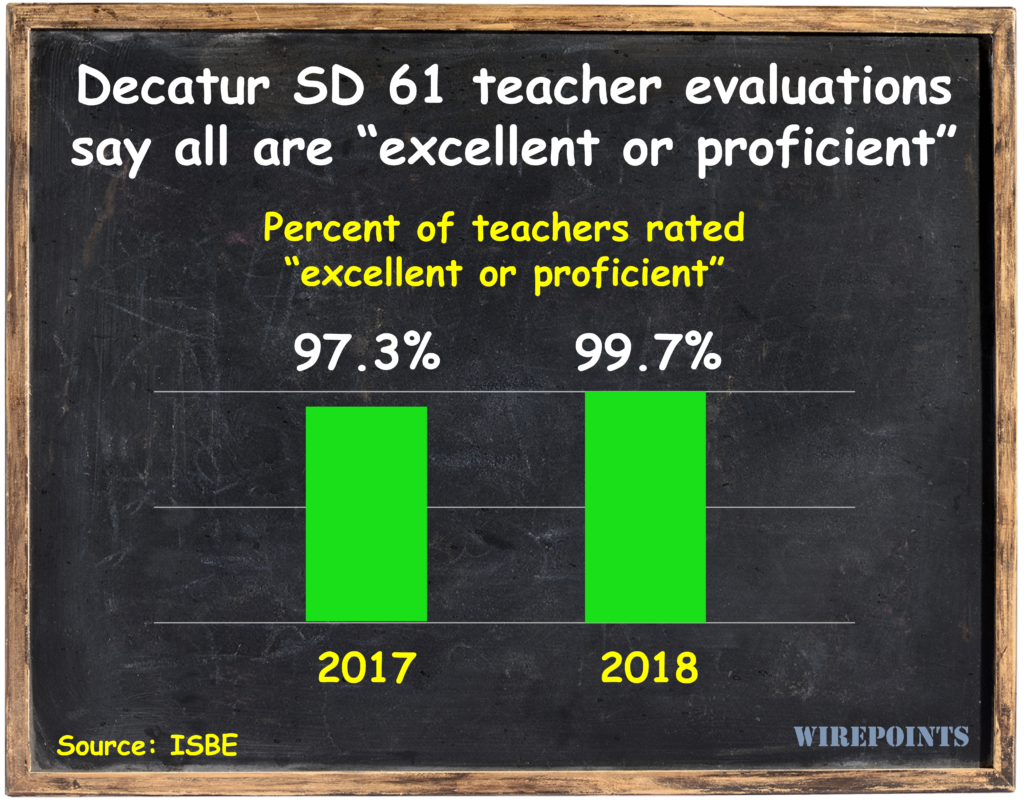

Decatur parents are being told their teachers are great based on what the state report card says. Over 97 percent of Decatur educators were evaluated as “excellent or proficient” in 2017. In 2018, 99.7 percent were rated “excellent or proficient.” So, Decatur has virtually no teachers that need improvement?

And that’s not just true of Decatur. ISBE’s report card says that 97 percent of teachers statewide were rated “excellent or proficient” in 2019. Illinois’ teacher evaluation process is broken.

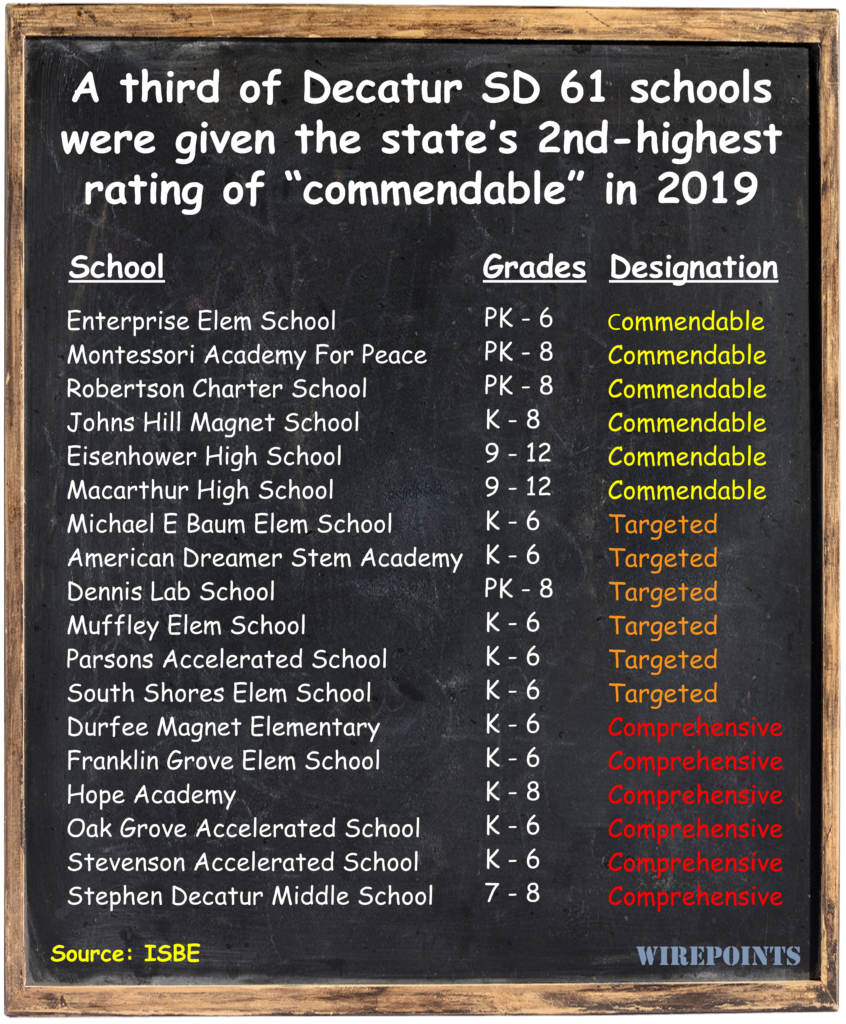

Then there are the state’s four “Summative Designations” for schools. Despite their dismal student outcomes, a third of Decatur schools were given the state’s 2nd-highest rating of “commendable” in 2019.

Take Decatur’s Montessori Academy for Peace, for example. There, only 6 percent of black students can do math and only 15 percent can read at grade level. And in Robertson Charter School, only 2 percent of all students can do math and only 7 percent can read at grade level. Yet ISBE labels both those schools as “commendable.”

It’s the same story everywhere

Decatur may be the poster child for the education system’s failures, but it’s far from the only example. The same story of poor student achievement and near-zero accountability can be seen across the state.

Take, for example, reading proficiency for black 3rd-graders in 2019. In Rockford, just 7 percent were proficient. In Dolton SD 149, 7 percent. In Cahokia, 5 percent. In Peoria, 8 percent.

Same for Hispanic 3rd-graders. In Elgin, just 11 percent could read at grade level. In Waukegan, 16 percent. In Aurora East, 13 percent. Harvard SD 50, 9 percent. And it’s not just minorities who are failing. Just 15 percent of white 3rd-graders in East Alton could read at grade level. In Quincy, 28 percent. In Mount Vernon, 25 percent. And in Plano, 11 percent.

Chicago Public Schools outcomes, while higher, still leave only a quarter of the district’s 330,000 kids able to read or do math at grade level.

Yet the parents in districts like these are told their children are performing well. A majority of students are listed as “on track” to graduate, ranging from 56 percent “on track” in Waukegan to more than 87 percent in Mount Vernon HSD 201. Parents are also told their student’s teachers are top-notch. The share of “excellent or proficient” teachers ranges from 91 percent in Chicago to 100 percent in Decatur and Mount Vernon.

And while a majority of students in these districts do end up graduating, ranging from a low of 66 percent of students in Rockford to 84 percent in Quincy, most are not graduating college or career ready. Less than a quarter of 11th-grade students can read or do math at grade level in most of those districts.

That represents tens of thousands of students pushed up and out of Illinois’ education system every year without the basic skills they need.

Illinois’ educational-industrial complex

How does Illinois’ education system remain intact given its many failures? The answer is simple: it’s designed to self-perpetuate.

A weave of labor laws, hundreds of districts, generous salaries, constitutionally protected pensions, powerful superintendents and even more powerful unions ensure the system is protected against criticism from parents and taxpayers. The entire $38 billion system – propped up by the symbiotic relationship between unions and lawmakers – can be described as an entrenched educational-industrial complex.

Here’s how it’s kept intact:

The labor contracts

At the heart of Illinois’ educational system are some of the most union-friendly collective bargaining laws in the country. Those laws compel – force – school district officials to negotiate with Illinois teachers unions.

What results are multi-year labor contracts that guarantee all types of protections and benefits for union members: job security, automatic raises and automatic inflation bumps, sick leave perks, pension pickups, end-of-career salary spiking, employment protections and more.

Decatur’s current contract is four years long, which is typical, but sometimes contracts are even longer. Palatine, for example, signed a 10-year long agreement in 2016.

Nobody in the private sector gets protections and guarantees like that. On top of that, the state’s labor laws allow administrators and the unions to keep contract negotiations secret from the public. Taxpayers don’t get a seat at the table and they don’t know the details until after the contracts are already agreed to.

And if the unions don’t like what a district offers during contract negotiations, they can strike. Striking is the most powerful tool at their disposal. Often just the threat of a strike is enough for school boards to give in to union demands.

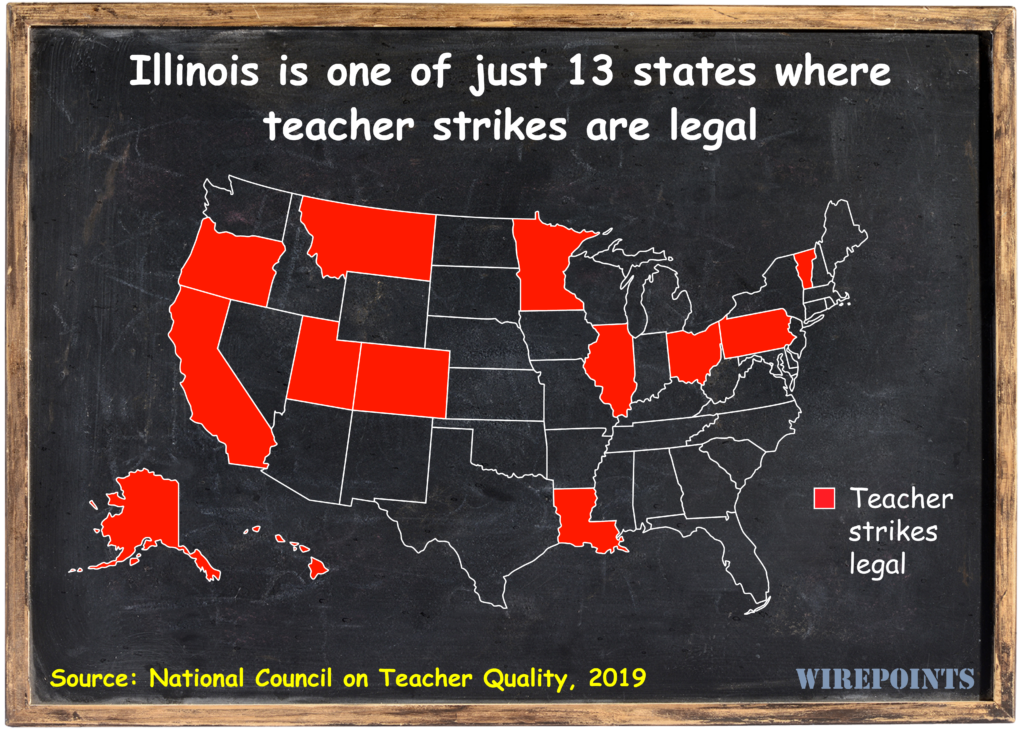

Most states aren’t reckless enough to give teachers unions that much power. Illinois is one of only 13 states Illinois’ educational-industrial complex – and the only one of its neighbors – to legally allow strikes, according to the National Council on Teacher Quality.

Contrast Illinois’ pro-union stance to that of states like Texas, Georgia and North Carolina, which prohibit their local school districts from bargaining with teachers unions. Those states prioritize parents over public sector unions.

The big money

Illinois’ big salaries and even bigger pensions ensure that few teachers and administrators want to upend the system.

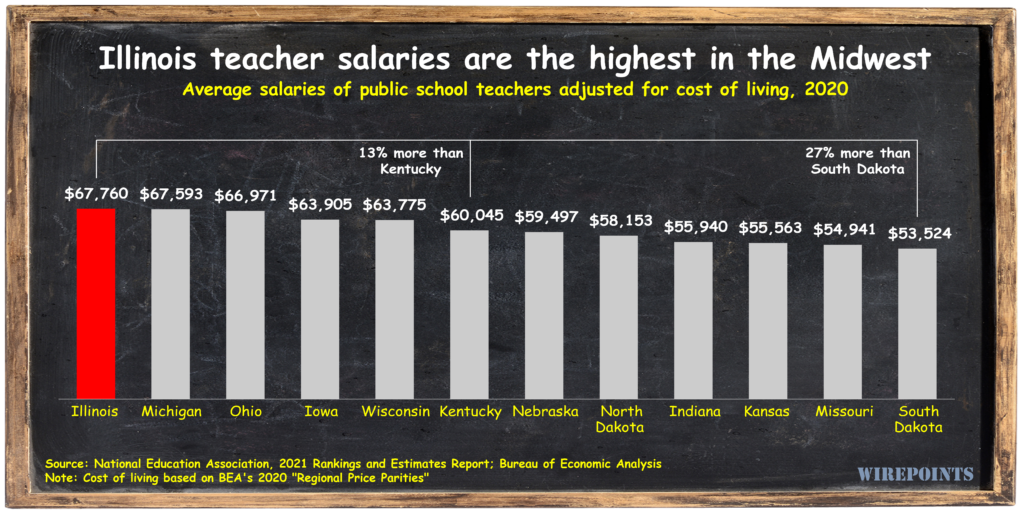

Average Illinois teacher salaries, at $67,760 for nine months of work, are the highest in the Midwest, according to the National Education Association. They are also the nation’s 11th-highest after adjusting for cost of living.

Those salaries, combined with generous pension rules, result in some of the biggest teacher pensions in the country. A 2019 study by Teacherpensions.org shows the median pension benefit for newly-retired Illinois teachers is the highest in the nation overall.

And a separate analysis by Wirepoints found Illinois’ pension formula is so generous that career teachers with 30 years or more of service retire today at an average age of 59 with starting pensions of more than $73,000.

Add up their expected years in retirement plus Illinois’ 3 percent compounded cost-of-living adjustment – one of the most generous COLAs in the country – and those career teachers will receive, on average, about $2.6 million over the course of their retirements.

Illinois’ education administrators have even more stake in the system. They earn an average of $114,000 a year, according to 2021 ISBE report card data, with 60 percent of Illinois’ 12,000-plus school and district administrators getting more than $100,000 a year.

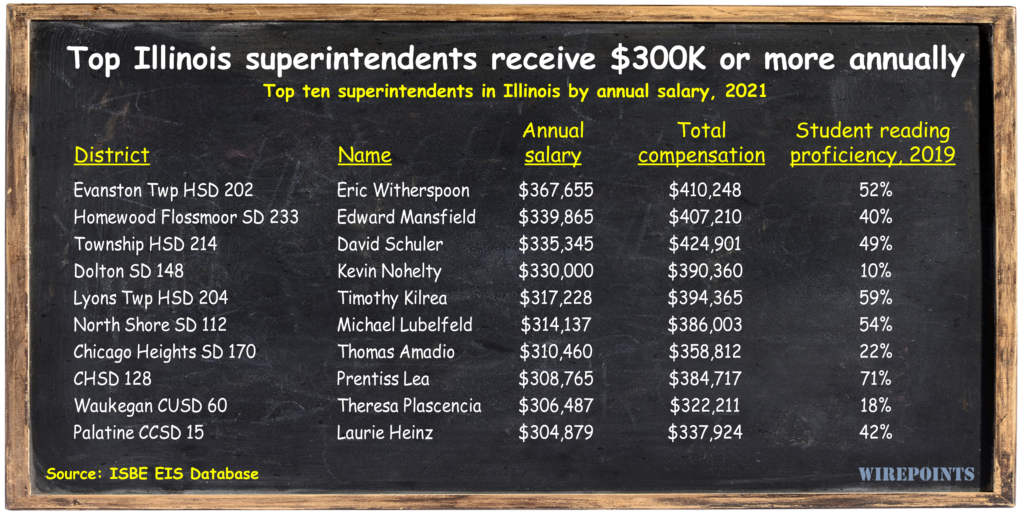

Illinois’ highest-paid administrators are state’s hundreds of district superintendents. They receive an average salary of $165,000 a year.

Take a look at the top ten. All are paid more than $300,000 a year. Kevin Nohelty of Dolton SD 148 is paid a salary of $330,000 to manage a district where only 10 percent of students can read at grade level. Theresa Placencia gets $306,000 in Waukegan where just 18 percent of students are proficient in reading.

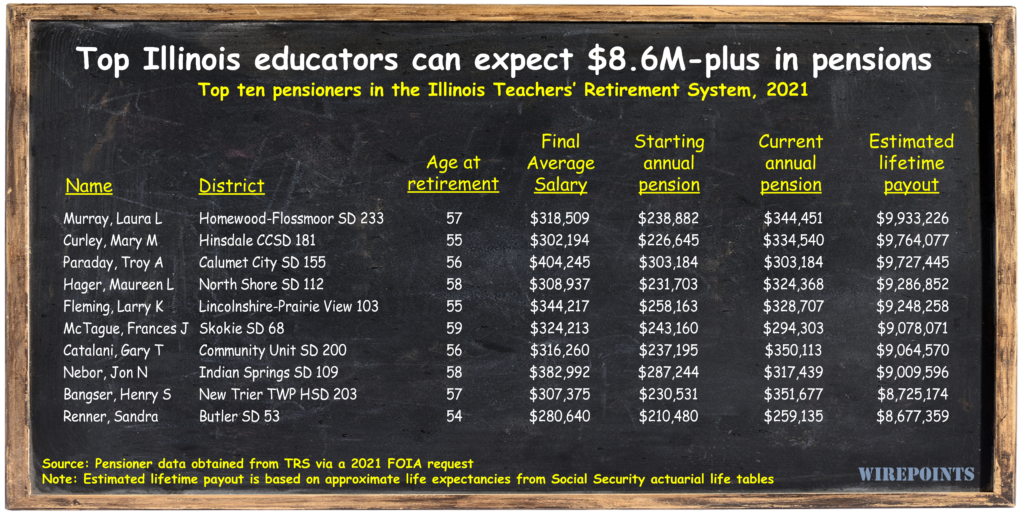

The numbers jump even higher when we look at superintendent pensions. The top retiree in the Teachers’ Retirement System is Laura Murray, a former superintendent of Homewood-Flossmoor.

She retired in 2008 at age 57 and received a starting annual pension of nearly $240,000. Today, thanks to Illinois’ automatic 3 percent yearly COLA, her annual pension is more than $344,000 a year. She can expect to collect about $10 million in benefits during retirement.

The entrenched bureaucracy

Superintendents entrench their power and influence through one of the most extensive education bureaucracies in the nation. Illinois has over 850 school districts – the nation’s 4th-most. Compare that to other large states with student populations with one million or more students and you’ll see what an outlier Illinois is. Florida has only 75 school districts, North Carolina, 115, Virginia, 132 and Georgia, 215.

And before you disparage the southern states for their “poor” education, know that Florida, with just as many low income and minority students as Illinois, has equal or better educational outcomes than Illinois. That’s even though Illinois spends 70 percent more per

student than Florida does.

At Wirepoints, we’re major proponents of local control and for pushing decision making to the lowest levels of government possible, but any analysis of Illinois’ school district structure reveals rampant overlap, duplication and bloat. Over a third of Illinois districts serve 600 students or less. Nearly 45 percent of districts serve only one to two schools. And over half the districts in Illinois are separate elementary and high school districts, rather than combined unit districts.

Take New Trier Township. There, six New Trier High School feeder districts all lie within the same border as the high school district. All seven districts could easily be a 12,000-student unit structure that consolidates multiple bookkeepers, superintendents, curriculum heads, etc.

Instead, taxpayers must support about 140 total district bureaucrats – including seven superintendents – earning big salaries and eventually even bigger pension benefits. (Remember that the state, and not local school districts, pays teachers’ pension costs.)

The back scratching

All those laws, staffing, money and bureaucratic organization make Illinois’ education system a political powerhouse.

Teachers unions give political contributions and votes to lawmakers. In return, lawmakers and local officials pass union-friendly laws, generous pay and even more generous benefits.

That’s another key part of the system’s resilience: nobody involved wants to stop the

gravy train. So much so that Illinois politicians are more than willing to enshrine union power in the state’s constitution. Lawmakers voted to include an amendment that would vastly expand union powers on the November 2022 ballot.

If voters approve the referendum, any chance of passing structural collective bargaining reforms will be blocked.

The “underfunding” myth

Despite the big money spent in Illinois, claims of an “underfunded” education system persist. Illinois state superintendents have in the past gone so far as to demand a $7 billion increase in state education funding in a single year.

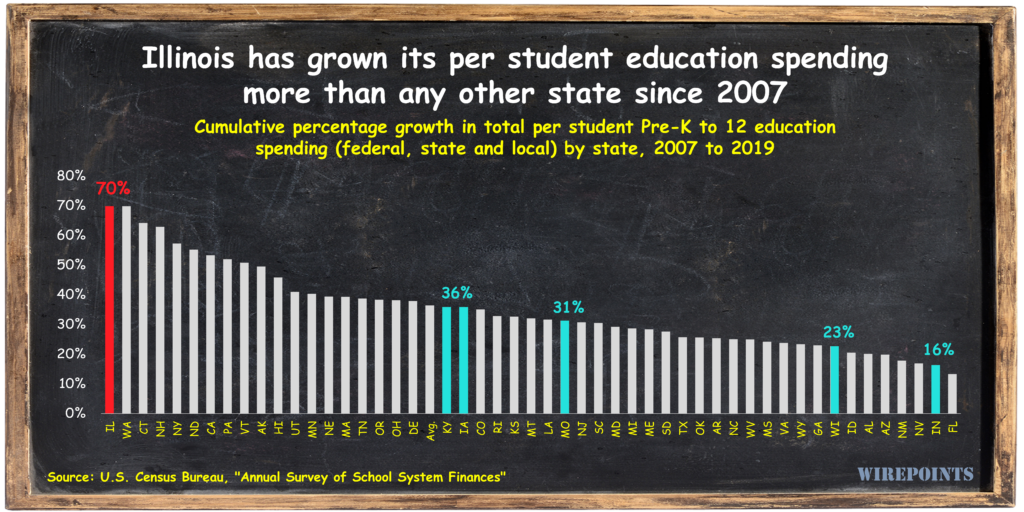

Illinois doesn’t need more education money. No state in the country has grown its spending more since 2007 than Illinois has. Spending is up 70 percent since before the start of the Great Recession. Compare that to neighboring states Wisconsin, up 23 percent and Indiana, up 16 percent.

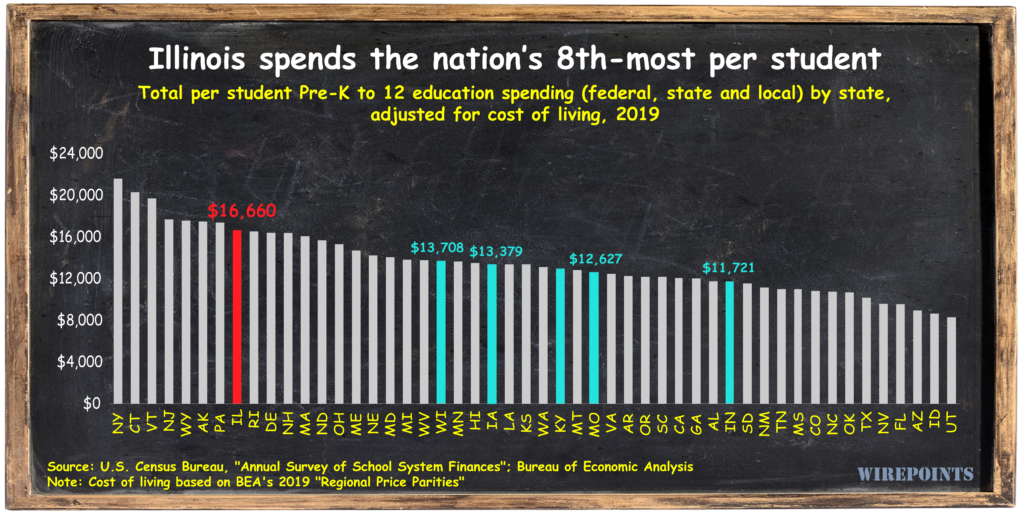

Today, Illinois spends $16,660 per student (local, state and federal) after adjusting for cost of living, the nation’s 8th-most and the highest spending of any state in the Midwest.

And for what? Illinois’ $16,660 is 40 percent more than Indiana’s ($11,721) and 70 percent more than Florida’s ($9,550) yet student achievement on national tests (NAEP) in those states is on par with or better than Illinois’.

Illinois education doesn’t need more money now, nor did it when former Gov. Bruce Rauner signed Illinois’ “evidence-based” funding plan into law in 2017.

Rauner bought into the “underfunding” myth despite Illinois’ then fastest-in-the-nation funding growth and its 13th-highest overall per student spending. Not to mention Illinoisans were already paying the nation’s second highest property taxes, most of that dedicated to education spending.

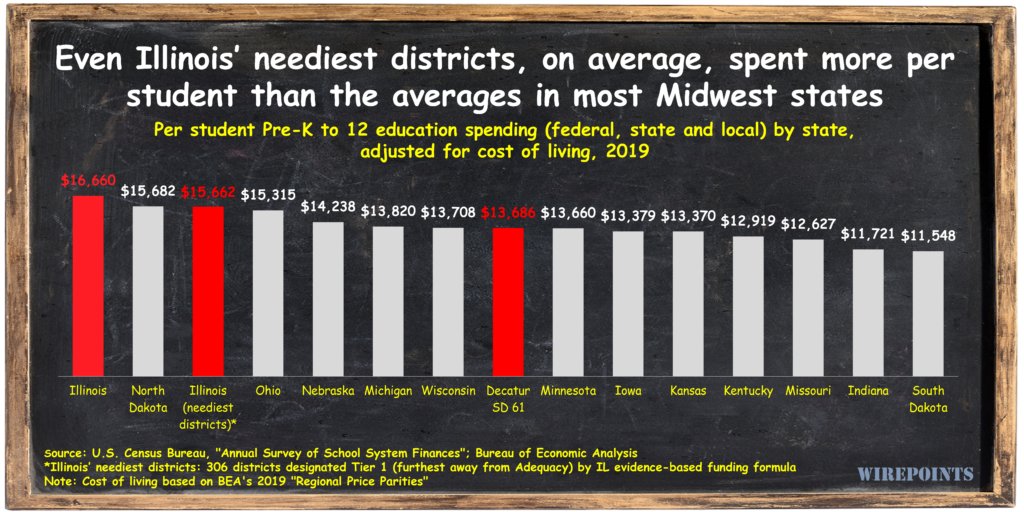

What about the rationale that poor districts need more money? Not true either.

Wirepoints isolated Illinois’ neediest Tier 1 districts in the U.S. Census data and found that, on average, they spent more ($15,622) than what every other Midwest state spent in 2019, with the exception of North Dakota.

Of course, that doesn’t mean every Tier 1 district spends that much, but it does show that the overall crisis in Illinois education isn’t about money. Decatur SD 61, for example, spent $13,686 per student, more than half of the states in the Midwest.

Embracing Choice

Parents are the last piece in Illinois’ educational puzzle. We don’t dismiss the hardships many parents face – their struggles are real – but the absence of outrage and general lack of interest in school board elections means they’re culpable for the system’s failures, as well. Too many parents don’t demand enough from their children or their schools. Other parents may want improvements, but they’re unwilling to fight for them. And yet others have fully ceded responsibility over their children to school bureaucrats.

But even when parents want to assert themselves – whether it’s to oppose CRT, sexually explicit curriculums, remote learning or masks – they find their rights consistently squashed. Not only in the minority and low-income school districts like Decatur, but in wealthier districts, too. Teachers unions and district administrators have long held all the power in education and the COVID-19 pandemic has only made that fact dramatically obvious.

Today, Illinoisans are stuck with a $38 billion system that demands little to no accountability from its educators. A system that prioritizes social promotion over literacy. A system that’s more obsessed with vague outcomes like equity and diversity than merit and competence. A system that compensates itself handsomely and performs self-serving evaluations, never mind the outcomes. And a system where parents have little to no choice but to send their kids to failing schools.

It’s no wonder so many parents have simply given up fighting or have packed up and left Chicago and other Illinois cities.

Illinois education requires a dramatic transformation. We’ll leave the details of that for a future report, but if recent polling is any indication, the changes will be driven by school choice.

Nearly 80 percent of Illinois parents and 67 percent of all Illinois adults support Education Savings Accounts, or ESAs, a recent EdChoice survey found.

That tracks with a new national poll from the American Federation of Children that shows 72 percent of registered voters support the concept of school choice, along with 72 percent of whites, 70 percent of blacks and 77 percent of Hispanics. Along political lines, even 68 percent of Democrats support school choice while 82 percent of Republicans are in favor.

Those are numbers even Illinois’ powerful educational industrial complex should fear.