Any way you cut them, the residential property taxes Illinoisans pay are punitive.

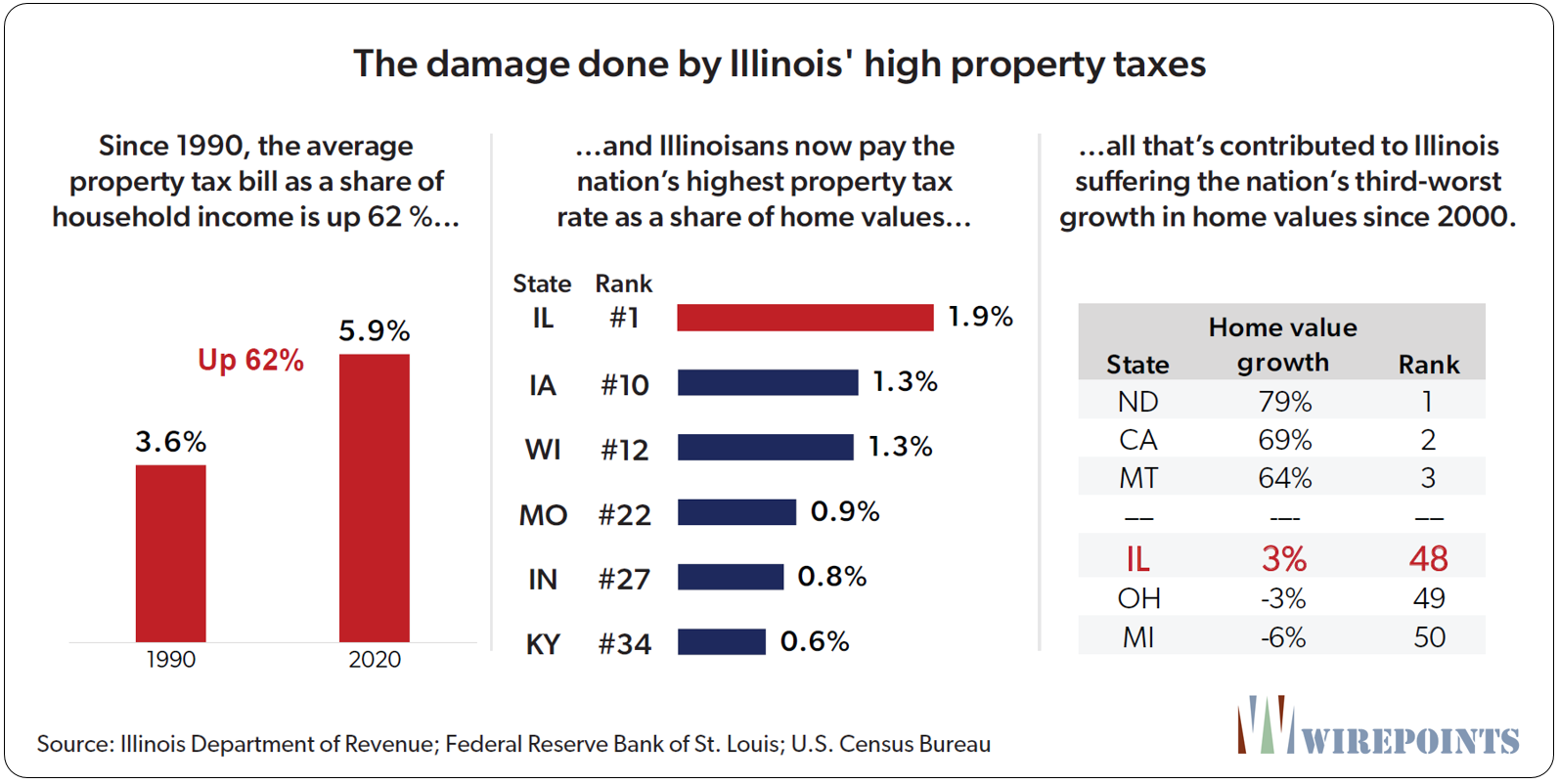

As a share of household incomes, they’re up more than 60 percent compared to three decades ago, never mind the law passed in 1991 meant to limit property tax increases.*

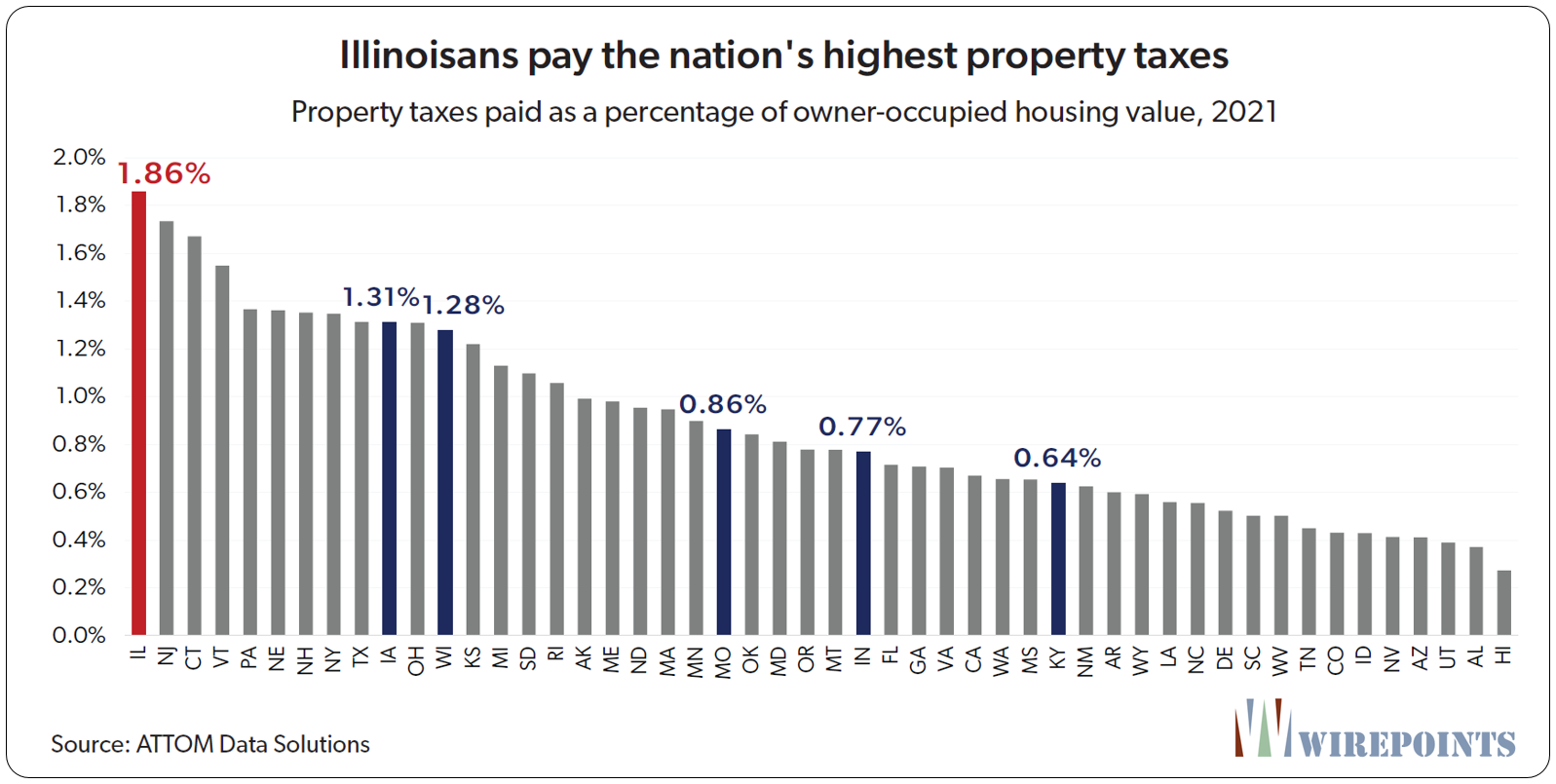

When measured as a percentage of home values, Illinois property taxes are now the highest in the country. ATTOM Data Solutions calculates Illinois effective tax rate equaled 1.86 percent in 2021.

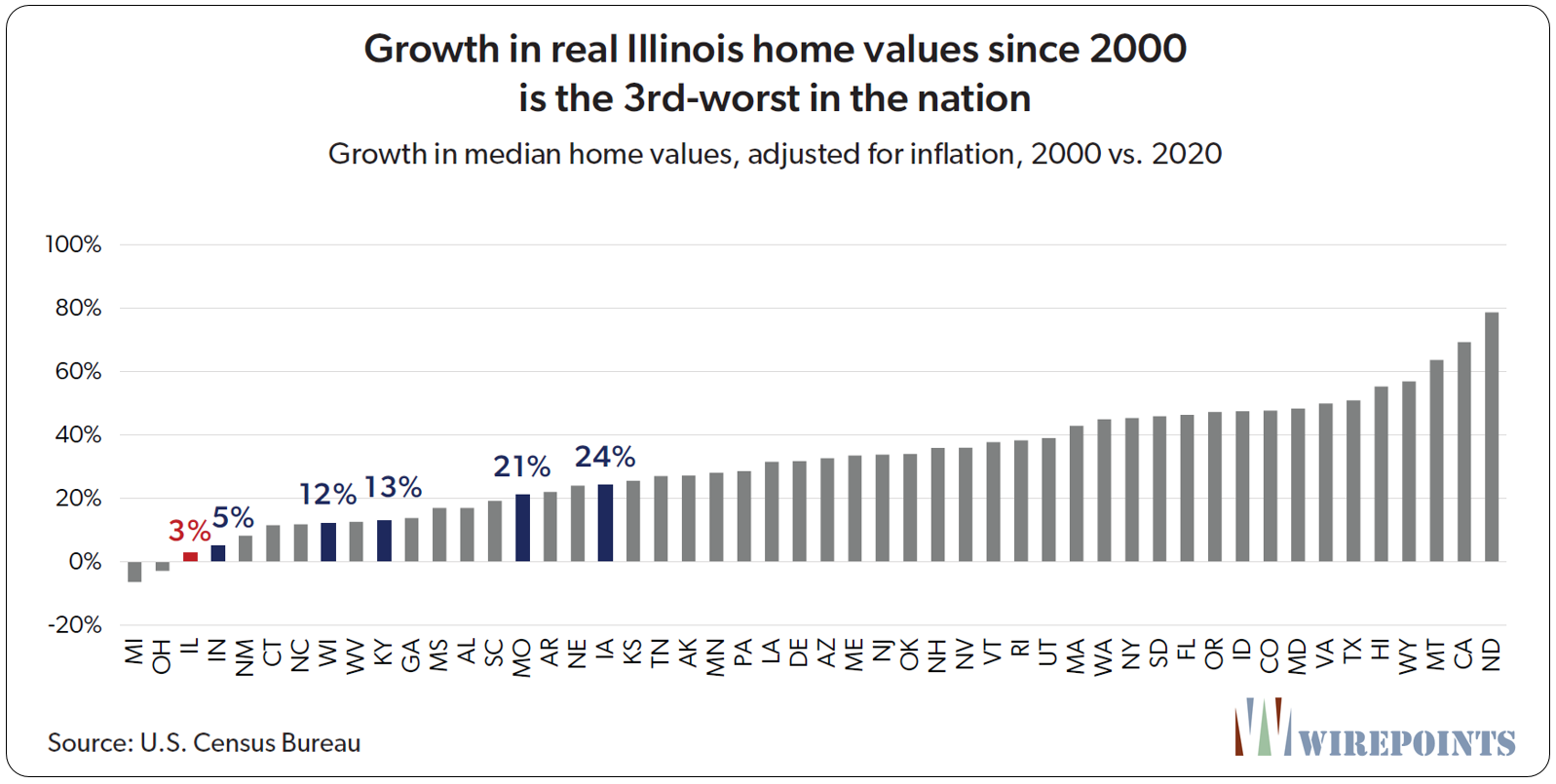

And as for their impact on house prices, property taxes have contributed to Illinois suffering the nation’s third-worst growth in home values over the last 20 years.

In this report, Wirepoints breaks down the property tax pain felt by Illinoisans. We start with how the growth in tax bills over time has overwhelmed residents’ ability to pay for them. We also look at the data county by county, identifying places with the largest burdens and how they’ve changed over time.

In this report, Wirepoints breaks down the property tax pain felt by Illinoisans. We start with how the growth in tax bills over time has overwhelmed residents’ ability to pay for them. We also look at the data county by county, identifying places with the largest burdens and how they’ve changed over time.

We then look at Illinois’ effective property tax rates – property taxes as a percentage of home values – and compare them to those in the rest of the country.

Last, we look at how the growth in Illinois home prices compares to the rest of the country.

The punishing numbers – and Illinois’ outlier position nationally – make an overwhelming case for reforming the cost drivers of Illinois’ property tax crisis, from pensions to public sector collective bargaining laws to education spending.

If Illinois doesn’t reform pensions, roll back overly-friendly public union labor laws and reorganize K-12 education funding, residents will continue to flee from the highest property taxes in the nation.

Property taxes vs. household incomes

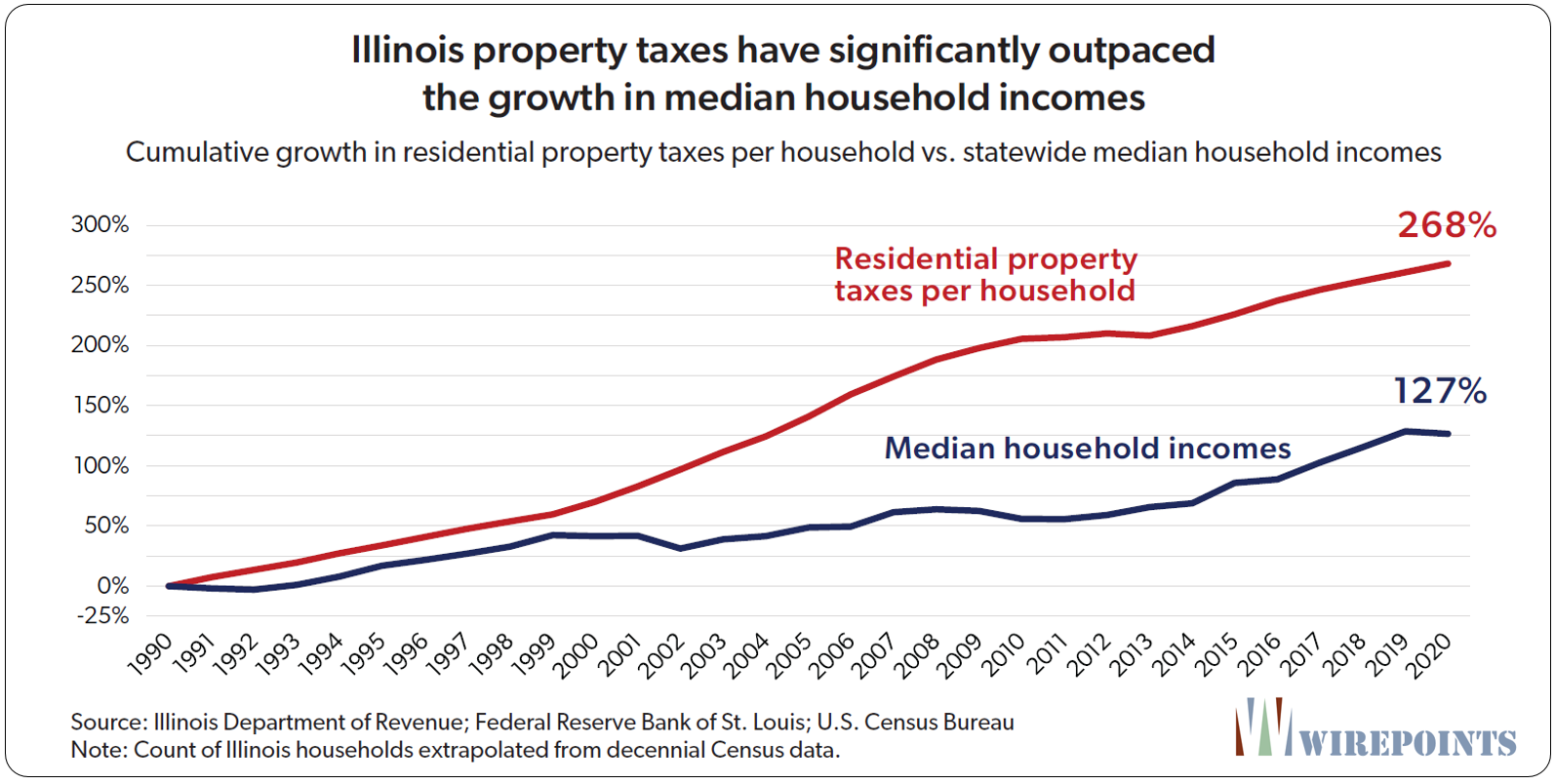

Over the last 30 years, Illinois property tax bills grew far faster than household incomes. That’s left Illinoisans with less money in their wallets for essentials like groceries, tuitions, mortgages, and retirement contributions.

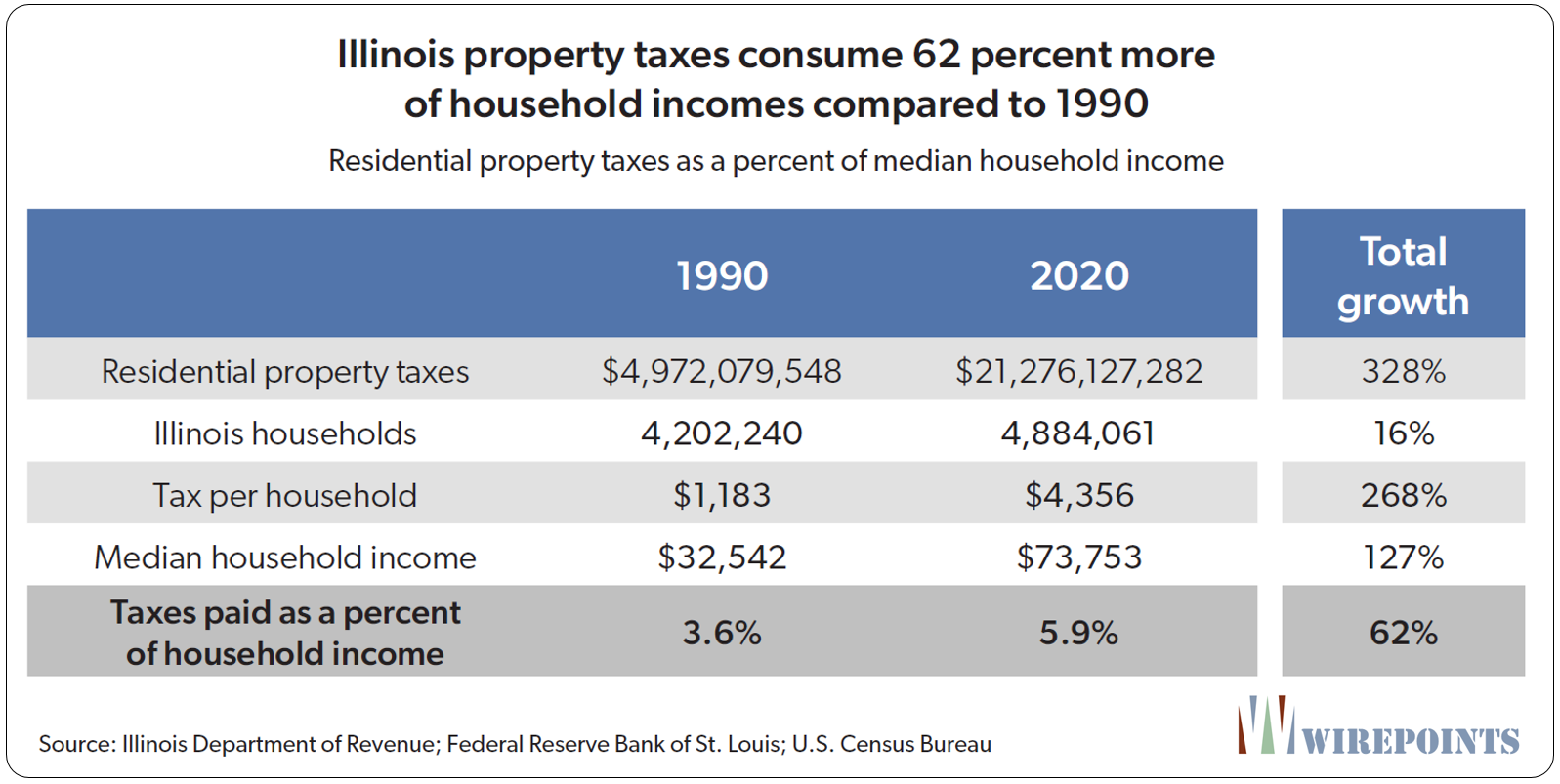

Residential property tax bills per household have grown 2.1 times more than median household incomes since 1990. Tax bills per household have grown 268 percent over the entire period, while incomes have only grown 127 percent. As a benchmark, inflation was up 98 percent over the same period.

The resulting change in burden has been significant. The average household now owes nearly $4,400 in taxes each year, up from $1,200 in 1990.

The resulting change in burden has been significant. The average household now owes nearly $4,400 in taxes each year, up from $1,200 in 1990.

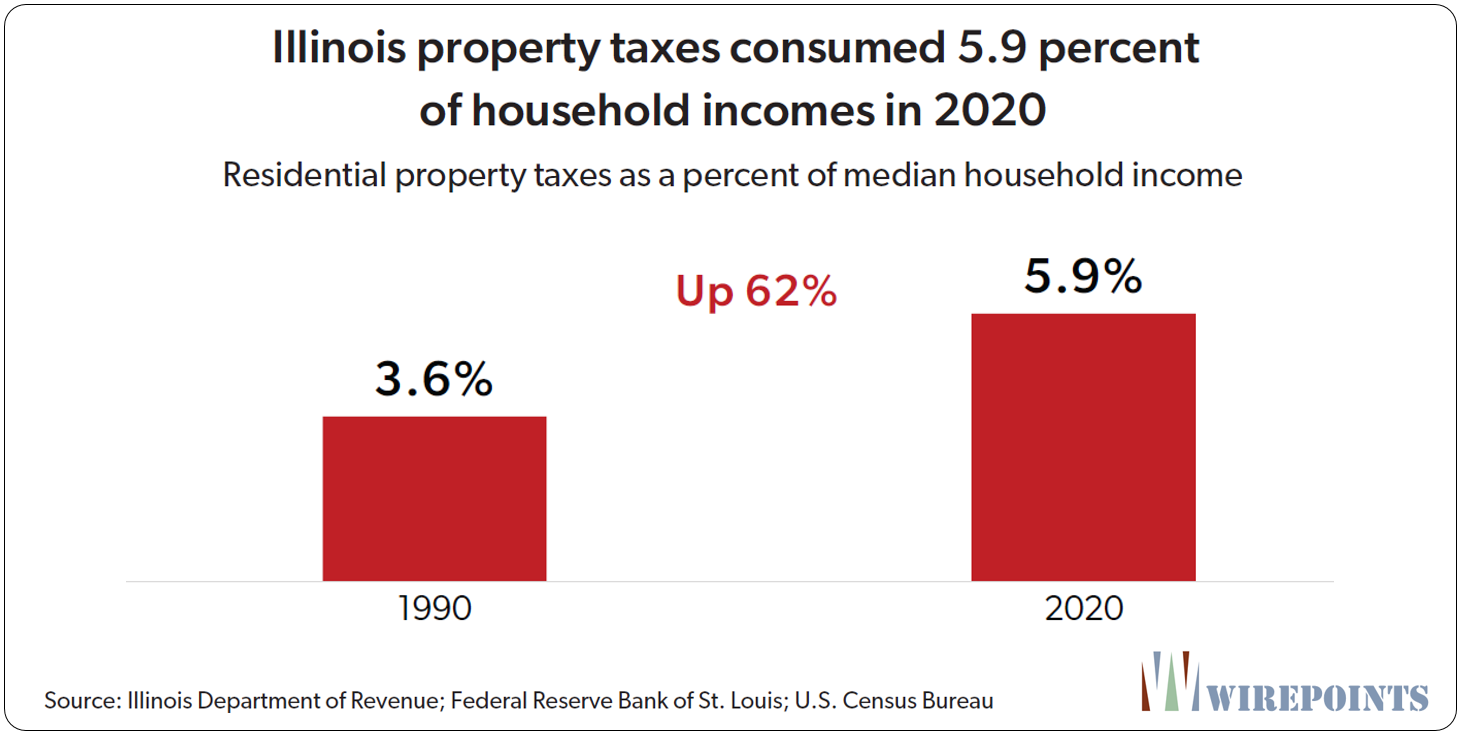

That bigger tax bill is taking a bigger bite out of residents’ incomes. In 1990, property taxes ate up 3.6 percent of median household incomes in Illinois. By 2020, they had jumped to 5.9 percent of incomes.

Think of it as an overall 2.3 percentage point tax hike. Or a 62 percent jump in the tax rate.

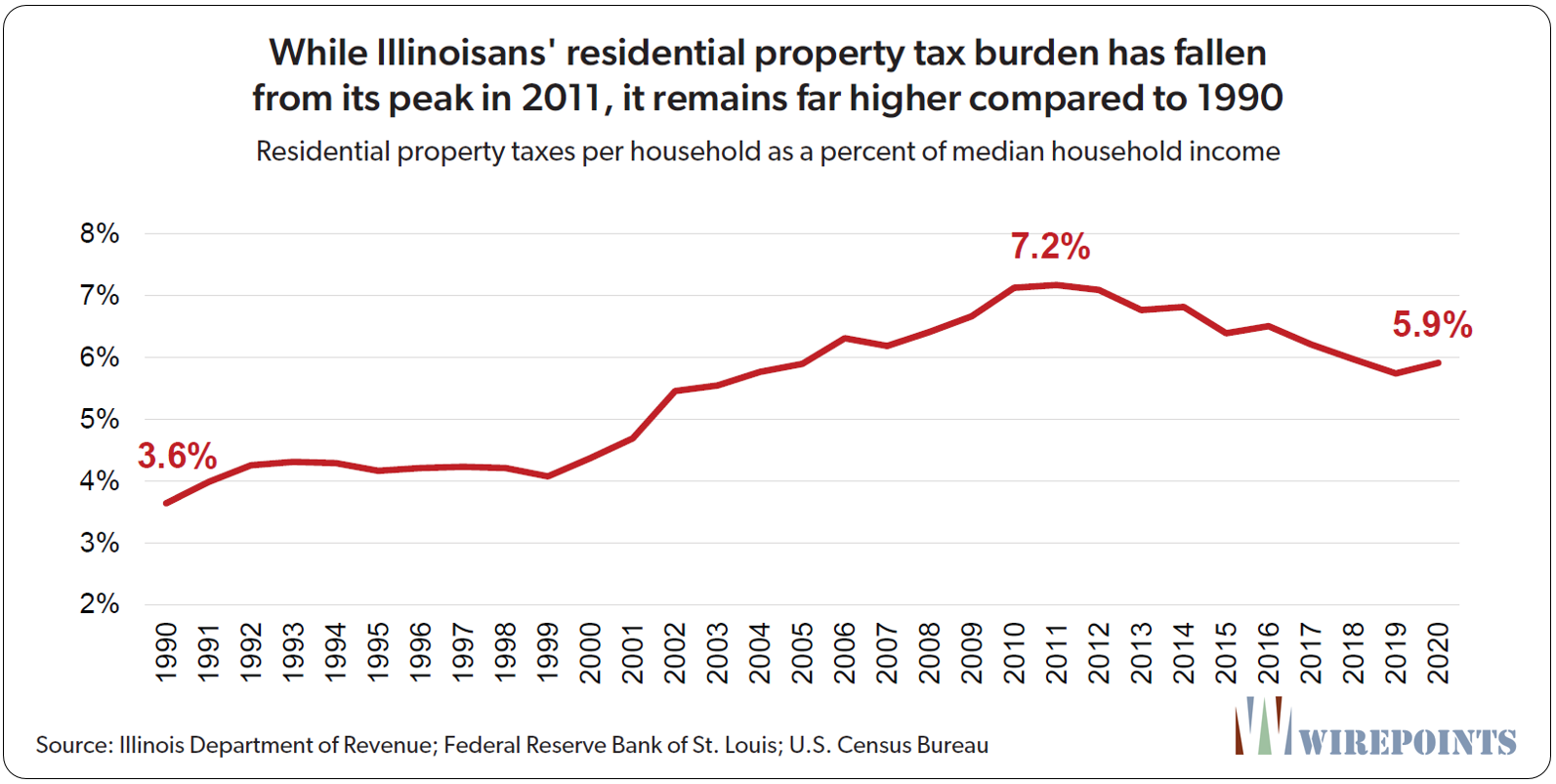

If there’s good news in the numbers, it’s that Illinois’ tax rate has actually dropped from its peak in 2011. Illinois’ property tax rates hit a record 7.2 percent in the aftermath of the Great Recession and the burst of the housing bubble.

If there’s good news in the numbers, it’s that Illinois’ tax rate has actually dropped from its peak in 2011. Illinois’ property tax rates hit a record 7.2 percent in the aftermath of the Great Recession and the burst of the housing bubble.

Since then, a slower-than average growth in residential taxes and a faster-than average increase in median household incomes, especially during the Trump economy, has dropped the rate down to 5.9 percent by 2020.

That said, it’s only a 20 percent decline off the peak. Illinois’ burden still remains higher than the 3.6 percent rate of 1990.

If the trend in tax and income growth since 2010 continues, Illinoisans will still have to wait 30 years for the property tax rate to return to the same level as it was in 1990.

If the trend in tax and income growth since 2010 continues, Illinoisans will still have to wait 30 years for the property tax rate to return to the same level as it was in 1990.

Even extreme measures can’t bring the rate down quickly. If Illinois were to freeze the total residential property tax levy where it is now, it would still take at least a decade for the rate to fall to the 3.6 percent Illinois homeowners were paying in 1990.

Property tax pain, county by county

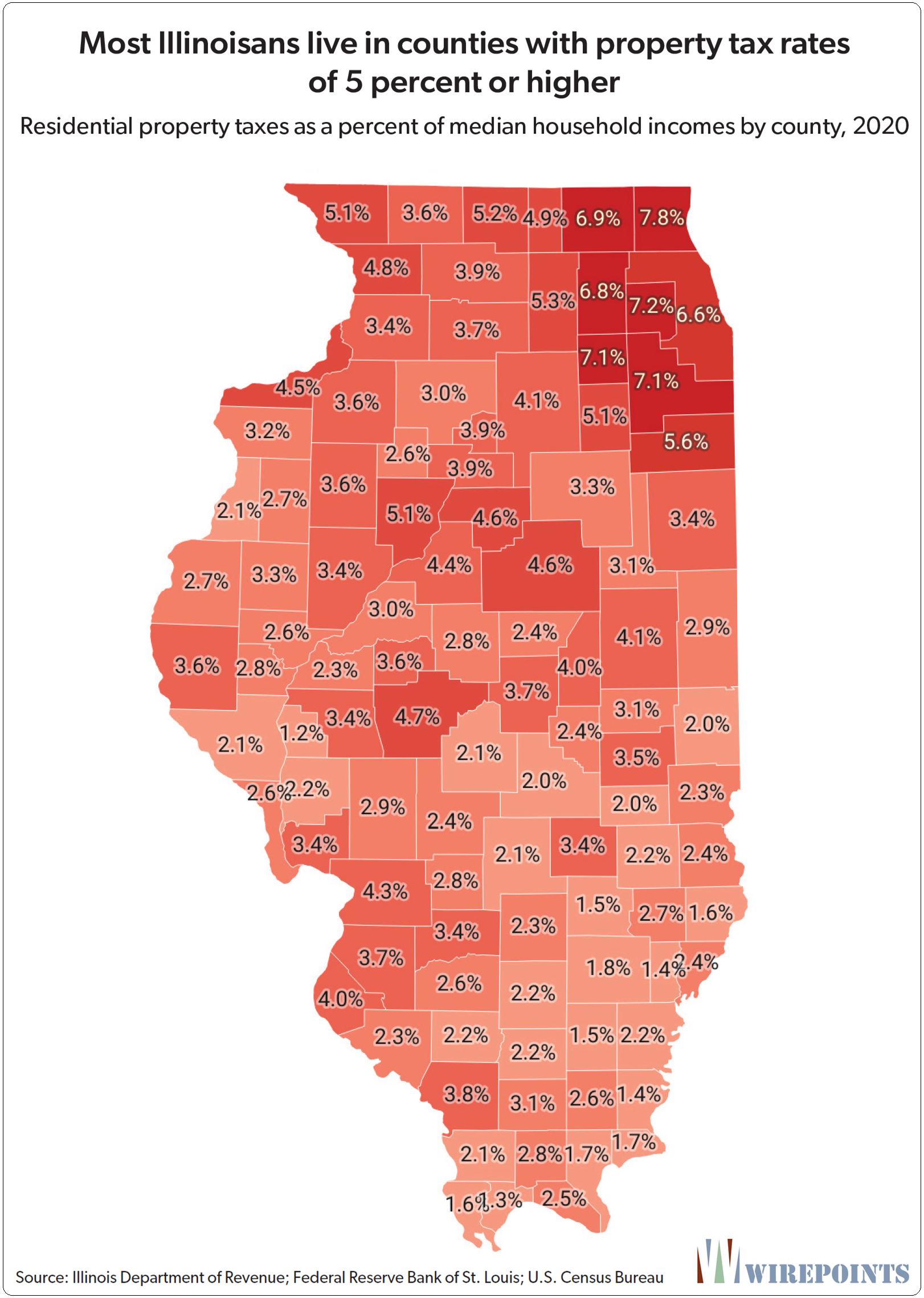

While the statewide numbers capture how big the property tax problem is, the pain is felt locally. Wirepoints calculated the impact of property tax growth on a county-by-county basis since the year 1990 and found that few Illinoisans have been spared from the pinch on their wallets.

Today, 13 counties – containing 70 percent of Illinois’ population – have residential property taxes that consume 5 percent or more of Illinoisans’ household incomes. In another 40 counties, the burden runs from 3 percent to 4.9 percent.

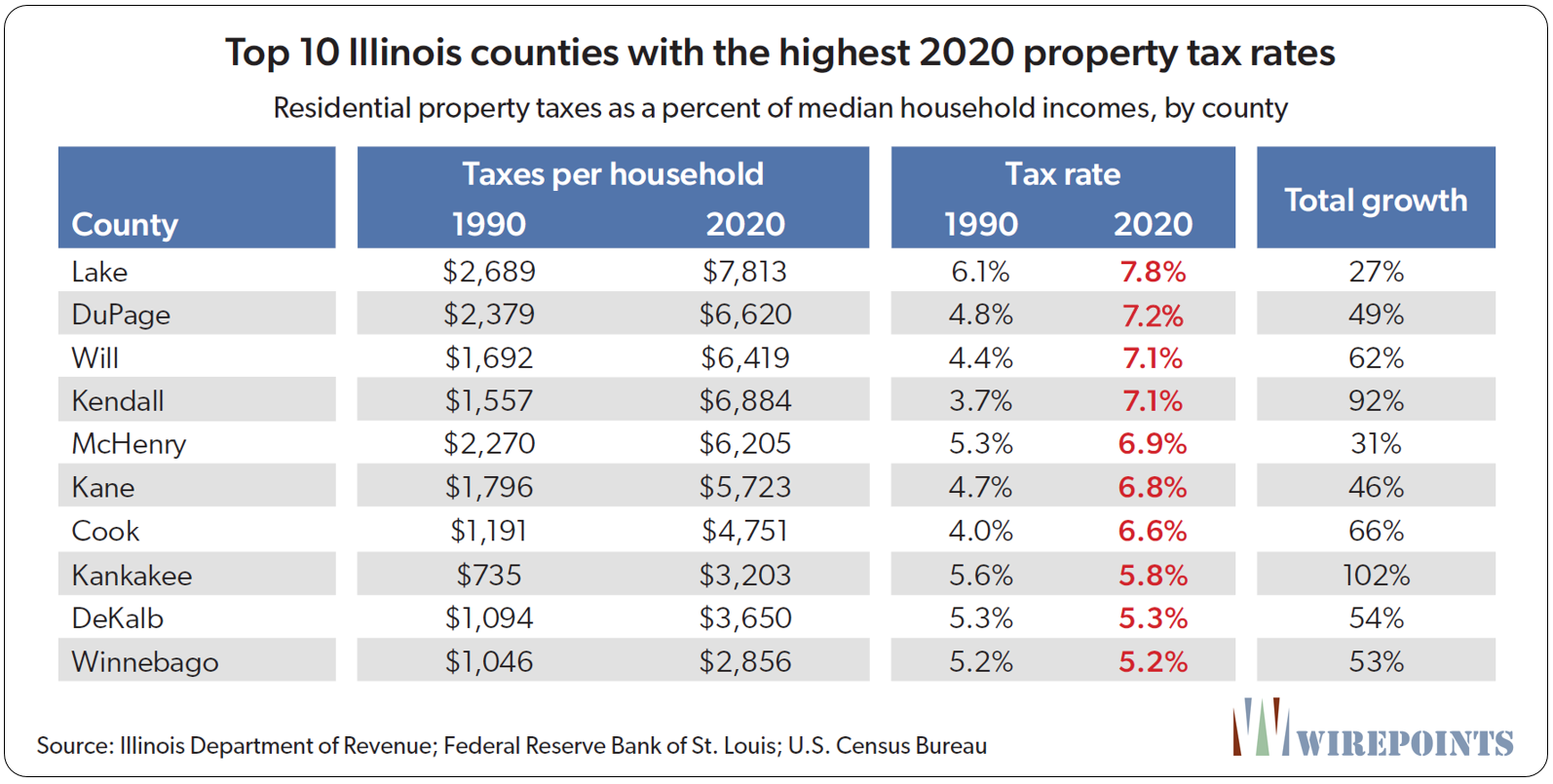

Homeowners in Lake County are burdened with the highest property tax rates in Illinois. In 1990, Lake County residents paid 6.1 percent of their household incomes toward property taxes. In 2020, residents paid 7.8 percent, a 27 percent increase. The average Lake County property tax bill is now over $7,800 per household.

Meanwhile, the residents of the other collar counties and Cook County pay about 7 percent of their incomes to property taxes, with average bills ranging from $4,700 to $6,600 a year.

Meanwhile, the residents of the other collar counties and Cook County pay about 7 percent of their incomes to property taxes, with average bills ranging from $4,700 to $6,600 a year.

Overall, the collar counties pay the highest taxes as a percent of income in the state. But it’s not just the Chicago suburbs that are taking a hit; taxpayers downstate have seen their taxes rise, too. In fact, most of the counties that have had the biggest growth in taxes on a percentage basis are found downstate.

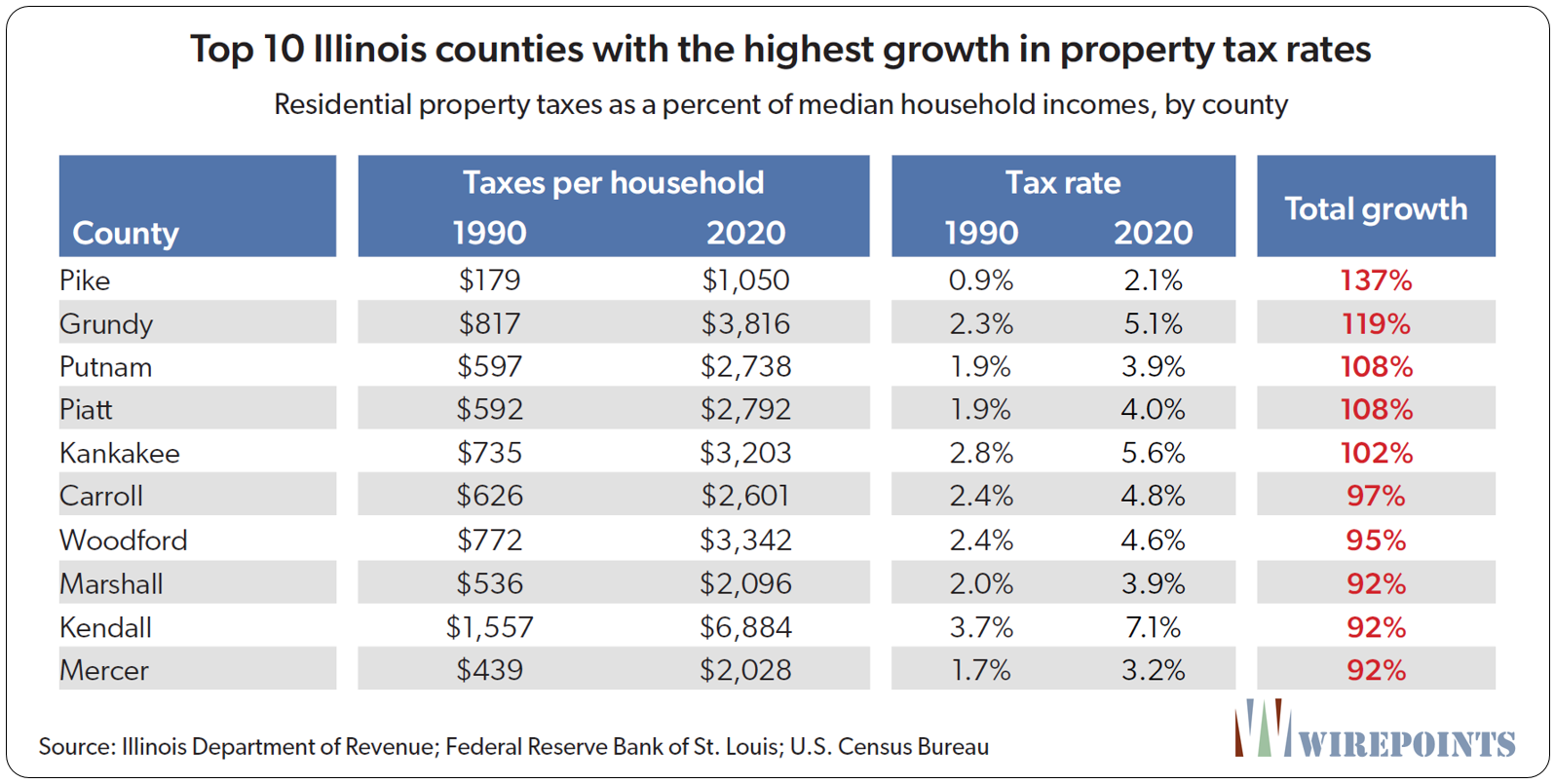

Pike County residents, though they pay relatively low taxes, have seen their rates jump 137 percent since 1990. Residents in Grundy County have seen their rates go up by 119 percent. Next come Putnam and Piatt counties, which both had growth of 108 percent.

Property taxes vs. home values

Property tax burdens are usually calculated by comparing property tax bills to home values. Take the total tax bill, divide it by the value of the home and you arrive at an “effective property tax rate.” It’s a useful way to compare burdens across states.

Under that measure, Illinois is the nation’s extreme outlier when it comes to property taxes. According to ATTOM, a leading curator of real estate data nationwide for land and property, Illinoisans pay the nation’s highest effective property taxes.

Illinois’ effective property tax rate equaled 1.86 percent in 2021 – more than double the effective rate that residents in Missouri (0.86 percent) and Indiana (0.77 percent) pay and triple what Kentuckians (0.64 percent) pay.

A separate study from last year by the Tax Foundation found that Illinoisans pay the country’s second-highest property taxes, behind only New Jersey.

A separate study from last year by the Tax Foundation found that Illinoisans pay the country’s second-highest property taxes, behind only New Jersey.

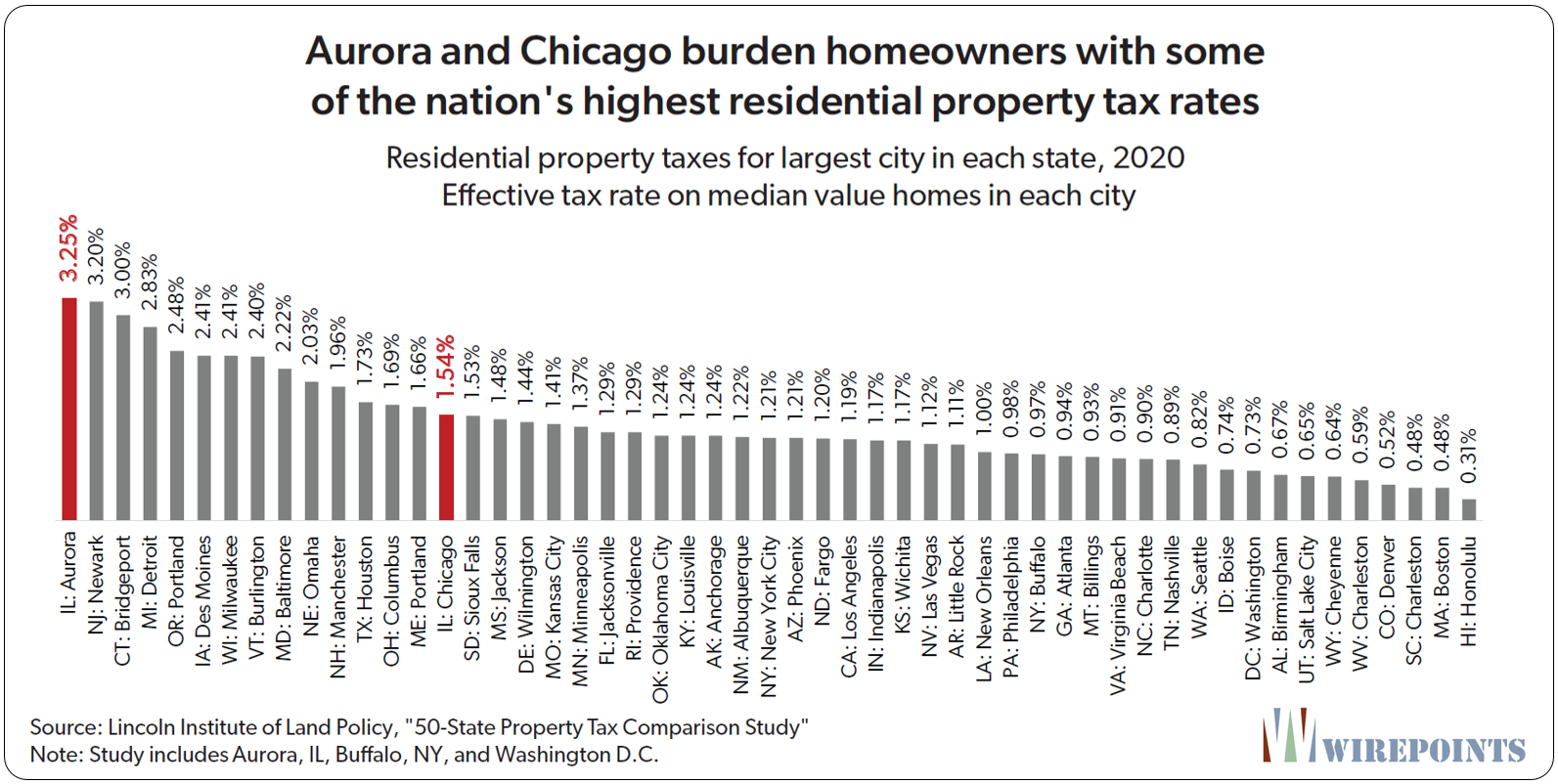

And yet another study by the Lincoln Institute Land Policy – measuring effective property tax rates in the largest city in each state, plus Aurora, Buffalo and Washington D.C. – found that Chicago and Aurora’s residential property taxes are some of the highest in the nation. Aurora hits its residents with an effective tax rate of 3.25 percent – the highest of the 53 big cities measured.

Chicago taxes are lower than that, but still high compared to most other cities. The Windy City hits its homeowners with a 1.54 percent rate, the 15th-highest of the cities measured. The average tax rate among all the cities was 1.34 percent.

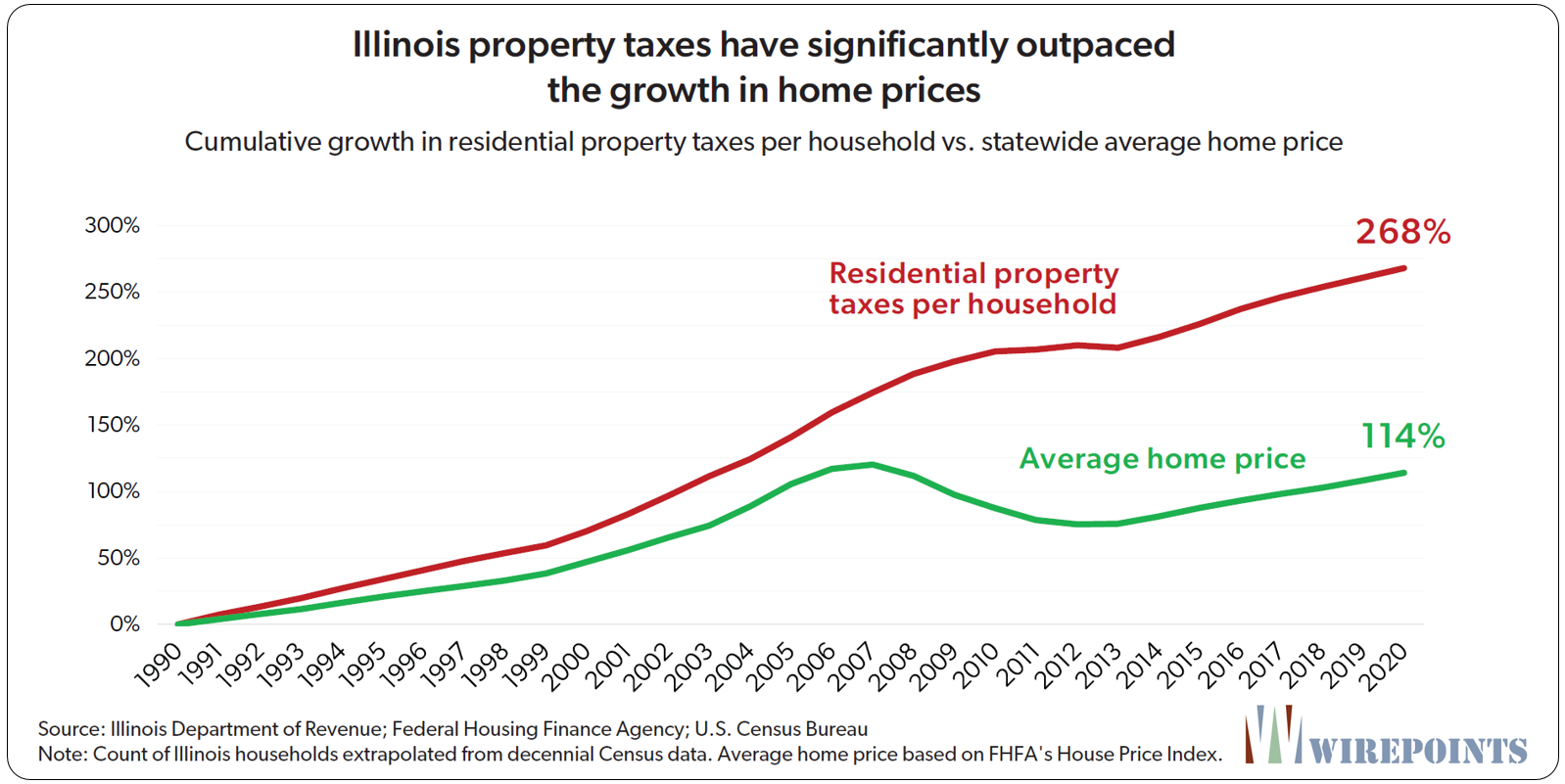

It’s not hard to see how Illinois ended up as the nation’s outlier when one compares the long-term growth in residential property taxes to the state’s home values.

It’s not hard to see how Illinois ended up as the nation’s outlier when one compares the long-term growth in residential property taxes to the state’s home values.

Residential property tax bills per household have grown 2.4 times more than average Illinois home values since 1990. Tax bills per household have grown 268 percent over the entire period, while average home values have only grown 114 percent. Inflation was up 98 percent over the same period.

Stagnant home values

Property taxes have inflicted damage to residents’ wallets in another way: they’ve contributed to the state’s lethargic home price growth. Higher property taxes mean lower home values, everything else equal.

Many people rely on their homes to provide for their financial and retirement security. Oftentimes, that’s where their entire net worth is. The more home values appreciate, the better off residents are.

In Illinois, median home values have barely kept up with inflation since 2000. Home values grew 55 percent while inflation grew 50 percent over the past two decades.

That’s made Illinois a national outlier. This state experienced the nation’s 3rd-worst growth in real median home values since 2000, growing just 3 percent. Only Michigan and Ohio, both of which had their inflation-adjusted home values shrink over the period, performed worse than Illinois.

Reducing property taxes through reform

Lawmakers have talked for years about lowering property taxes, but there’s been no real effort to structurally fix the problem. The legislature’s last real attempt, the 1991 Property Tax Extension Limitation Law (PTELL), has failed for decades. Most recently, Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s blue ribbon tax reform committee delivered no real solutions or even a final report.

Instead, politicians continue to make things worse by refusing to reform the major cost drivers of property taxes. Rather than reform existing pensions and reduce pension debts, lawmakers have increased benefits for government workers. Rather than reduce the collective bargaining powers of the public sector unions, lawmakers have granted them even more powers. And rather than actually address the problems with education funding, lawmakers have only thrown more state money at schools.

Some supporters of property tax reform believe in implementing a property tax cap. But capping the growth in property taxes won’t fix the real problem: local cost drivers. Local governments will simply hike other taxes and fees to pay for their pension, labor and education costs.

Pension reform, starting with a constitutional amendment to the state’s pension protection clause, collective bargaining reforms and local government consolidation are the only ways to structurally and permanently reduce Illinoisans’ property tax bills.

Illinois’ Property Tax Extension Limitation Law (PTELL) was passed in 1991 to provide tax relief from rising property taxes in non-home-rule taxing districts in collar counties DuPage, Kane, Lake, McHenry and Will. Today, property taxes in 39 counties, including Cook, are subject to PTELL. Under the law, increases in property tax extensions are limited to the lesser of 5% or the increase in inflation in the previous year.

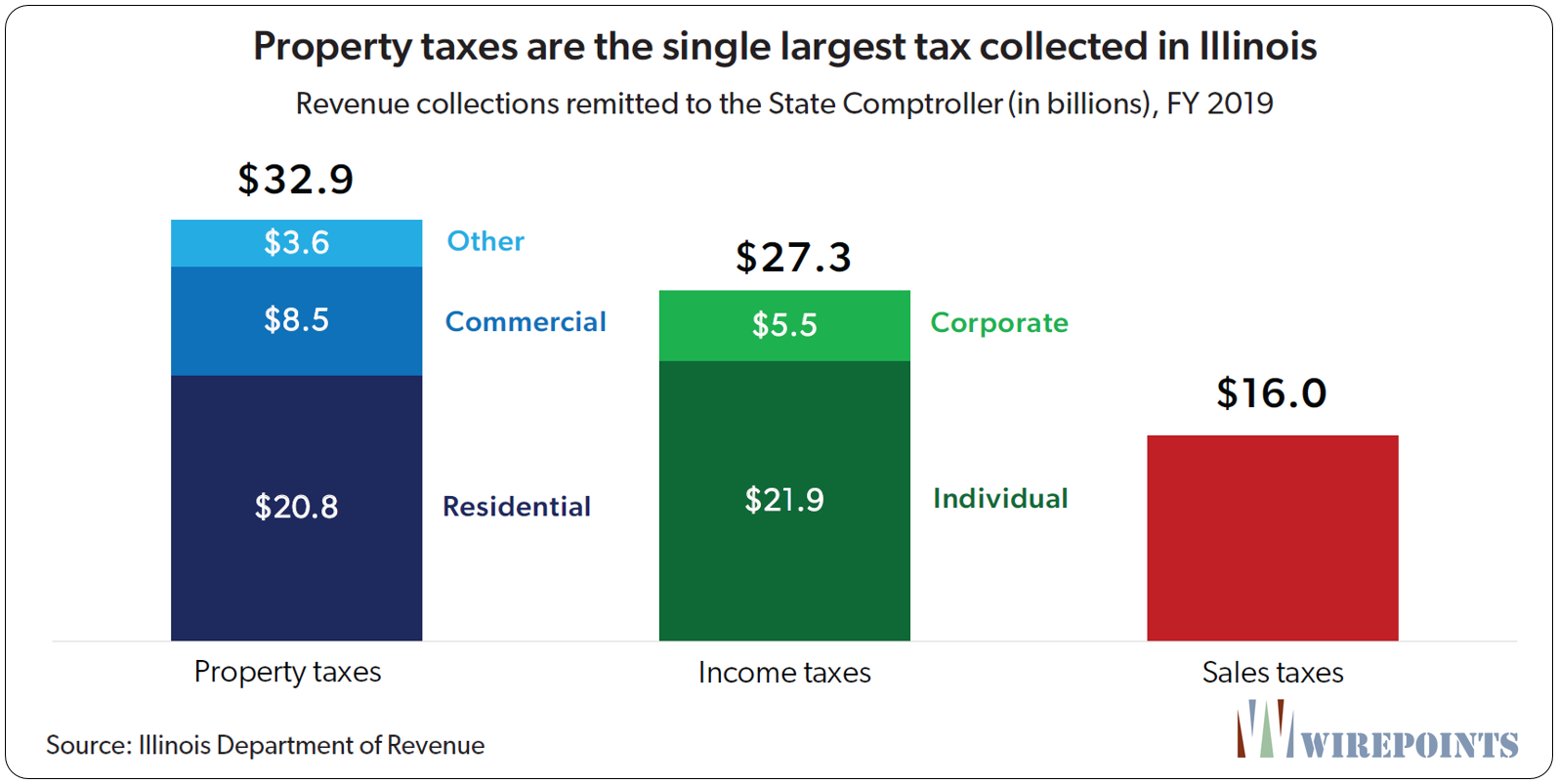

Illinoisans know they pay high property taxes, but what they may not know is just how big Illinois’ property tax revenues really are.

At $33 billion in annual revenues, property taxes are the single largest tax collected in Illinois, bigger than both income taxes ($27 billion) and sales taxes ($16 billion).

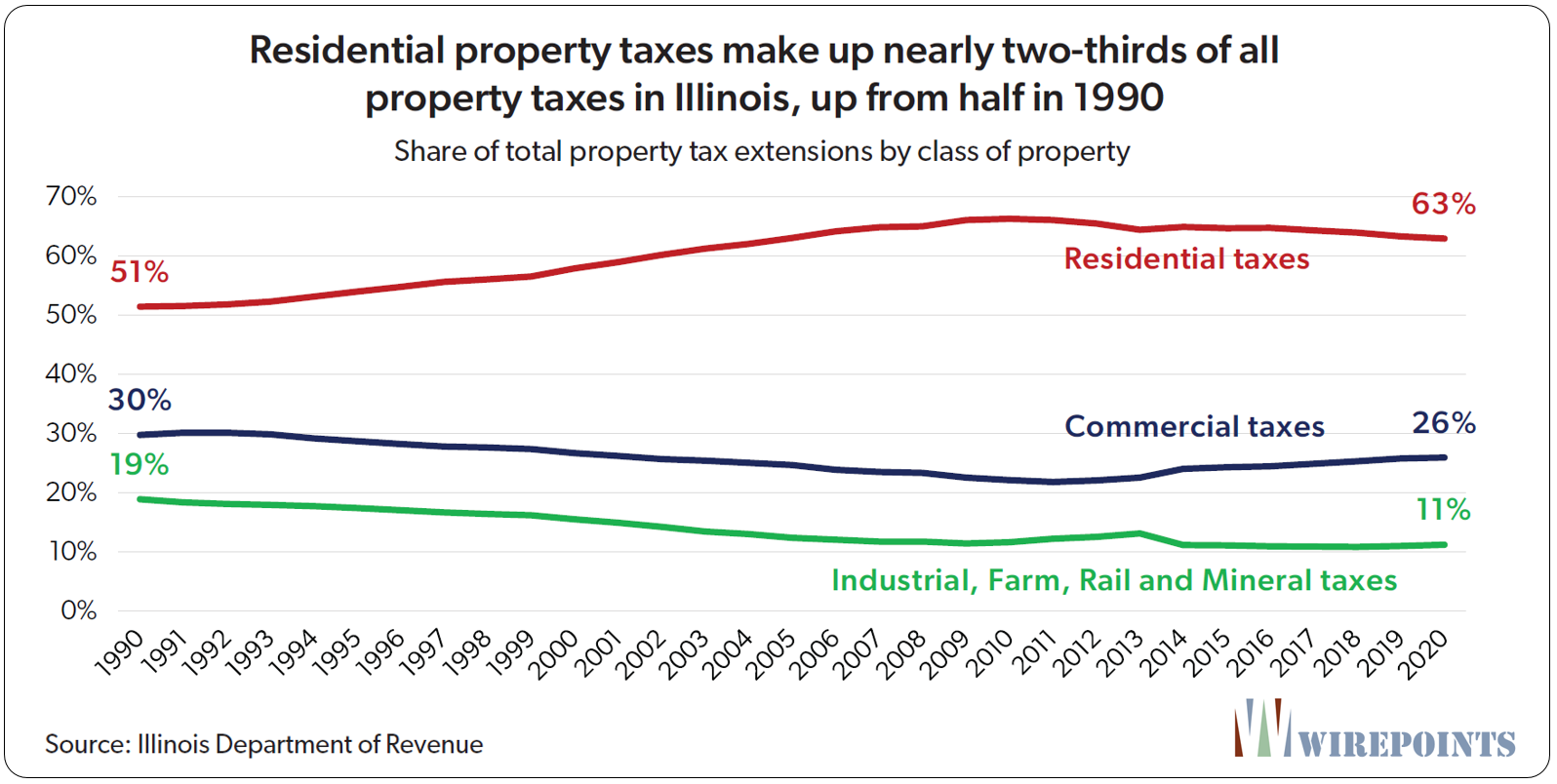

Part of the reason homeowners have felt such an acute increase in their tax burdens is due to an overall shift in statewide property taxes away from commercial and industrial properties to residential over the past 30 years.

Part of the reason homeowners have felt such an acute increase in their tax burdens is due to an overall shift in statewide property taxes away from commercial and industrial properties to residential over the past 30 years.

In 1990, residential property owners paid 51 percent of Illinois’ $9.6 billion in total property taxes. Commercial owners paid 30 percent and all other owners (industrial, farm, railroad and mineral) paid 19 percent.

Today, homeowners pay 63 percent of Illinois’ $33.4 billion in total property taxes. Next biggest are commercial property owners, who pay 26 percent. Other property owners pay the remaining 11 percent.