Illinois lawmakers have a lot of explaining to do regarding K-12 education spending and their continuous demands for billions more in state funding.

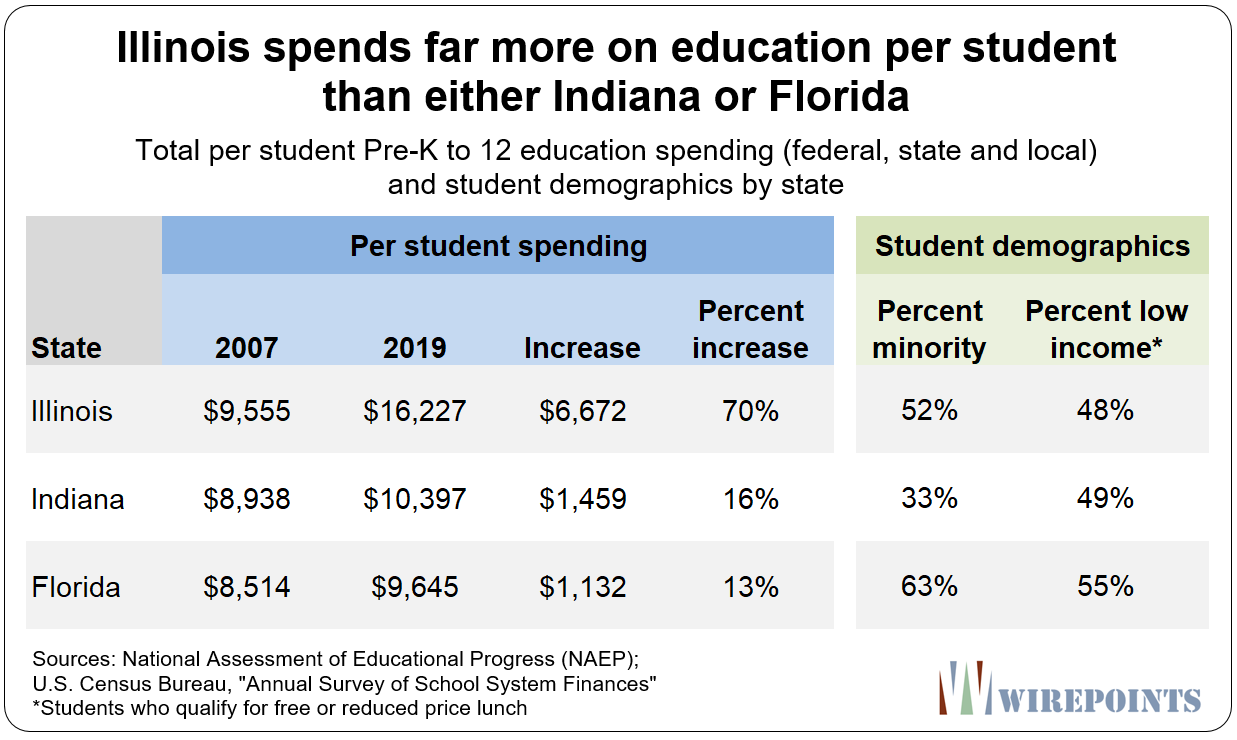

How is it that Illinois spends nearly 70 percent more per student (in federal, state and local dollars) than Florida does – a state with an even larger concentration of minority students than Illinois – and yet the Sunshine state largely performs the same or better?

And how is it that Illinois spends $6,000 more per student on education than Indiana – a state with the same share of low-income students as Illinois – and yet that state performs better on national testing than Illinois does?

And how is it that Illinois has been the biggest spender on education in the entire Midwest every year since 2010, and yet we’ve seen no real improvement in student achievement since then?

Those questions matter because Illinoisans are struggling under the nation’s 2nd-highest property taxes, nearly two-thirds of which goes to education; the state has hundreds of overlapping and duplicative districts with thousands of redundant administrators; teacher pensions are among the nation’s most generous; and overall per student spending in Illinois has increased by 70 percent since 2007 – the nation’s biggest increase.

Those questions matter because Illinoisans are struggling under the nation’s 2nd-highest property taxes, nearly two-thirds of which goes to education; the state has hundreds of overlapping and duplicative districts with thousands of redundant administrators; teacher pensions are among the nation’s most generous; and overall per student spending in Illinois has increased by 70 percent since 2007 – the nation’s biggest increase.

Most importantly, Illinois has continually failed to improve on student achievement. Results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), often called The Nation’s Report Card, show Illinois has basically flatlined since 2007.

Reducing Illinois’ $16,200 per student spending to Florida-like levels of $9,600, would mean a reduction of $12.8 billion in education spending per year, which would be the equivalent of a 40 percent property tax cut. (Total property taxes in Illinois totaled $31.8 billion in 2019).

Illinois lawmakers and the state’s education officials have gotten a free pass year after year when they’ve pushed for more K-12 dollars. More recently, former Gov. Bruce Rauner declared the state’s education spending inadequate in 2017 and worked with the educational establishment to pass a new “evidence-based” funding model that demands billions more in state spending over a decade. Gov. J.B. Pritzker has embraced that same “underfunded” narrative and has continued to push for additional funding every year.

Few, though, have asked just what that money is doing and where it’s going.

The details: Illinois spends far more on education than Florida or Indiana

We focused this piece on Florida and Indiana because they have had the slowest growth in per student spending in the nation since 2007, 13 percent and 16 percent, respectively.

In contrast, as Wirepoints documented in its recent report: Illinois education spending soars while outcomes flatline, Illinois education spending per student grew by 70 percent. That’s according to 2007 and 2019 education spending data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau.*

In 2019, the most recent year available from the U.S. Census, Illinois spent $16,227 per student. That’s the 12th-most of any state and 8th-most when adjusted for cost-of-living.

In 2019, the most recent year available from the U.S. Census, Illinois spent $16,227 per student. That’s the 12th-most of any state and 8th-most when adjusted for cost-of-living.

In contrast, Indiana spent just $10,397, the nation’s 37th-most. Florida spent just $9,645 per student, the 45th-most in the nation.

In all, Illinois spent 56 percent more than Indiana and a whopping 68 percent more than Florida in 2019.

For all its spending, Illinois does no better

For all its spending, Illinois does no better

With Illinois spending so much on education and Indiana and Florida spending far less, one might expect Illinois’ student achievement to significantly surpass both states. An examination of National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) test scores shows that’s not the case.

Illinois’ results were largely worse than Indiana and Florida’s over the entire 2007-2019 period.

Take for example, 4th-grade math. Illinois students have always scored below the national average, while students in Indiana and Florida have scored at or above the average.

In 2019 alone, Illinois’ average math score was 237, significantly lower than the nationwide score of 240. In contrast, Indiana and Florida scored 245 and 246 respectively, significantly higher than the national average.

Or look at 8th-grade reading scores. Illinois students consistently scored a few points above Florida and a few below Indiana, though by 2019 each state’s scores had largely converged.

The point remains that, for all of its spending over the 2007-2019 period, Illinois’ student achievement is often worse than two of the lowest spending states in the country.

The point remains that, for all of its spending over the 2007-2019 period, Illinois’ student achievement is often worse than two of the lowest spending states in the country.

State officials may try to argue that Illinois’ situation is different due its concentration of poor and minority students – but Indiana has the same share of low income students as Illinois. And Florida actually has an even greater share of minority and low income students than Illinois does.

If higher spending was so necessary to boost student achievement of low-income and minority students, then Illinois’ scores should be far better than Florida’s – not similar or worse.

If higher spending was so necessary to boost student achievement of low-income and minority students, then Illinois’ scores should be far better than Florida’s – not similar or worse.

Of course, there are many factors that go into understanding student outcomes – far more than just per student spending. And Florida and Indiana are just two states out of 49 to compare to. But the fact that both states have grown their spending so little, and spend so much less than Illinois overall, warrants the comparison.

A forthcoming deeper look at Illinois education spending will reveal that too much of Illinoisans’ money is funding hundreds of overlapping, duplicative school districts, a bloated, growing administrative bureaucracy, overgenerous retirement perks, a regressive pension funding system and multimillion-dollar lifetime pensions.

Those are the many reasons why Illinois spends such a premium on education and yet gets nothing for it.

*Wirepoints chose 2007 as the base year to avoid the volatility in education funding during the Great Recession.