Illinois’ pension crisis has been a growing problem for decades, and its negative effects on state residents are well documented.1 Economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic and related government shutdown orders threaten to bring that long-running crisis closer to its breaking point.

The state’s five pension systems collectively held nearly $139 billion of debt at the end of fiscal year 2019, according to state financial reports.2 But that number actually undersells the size of the state’s debt crisis. Moody’s Investors Service, a credit rating agency that uses assumptions more in line with private sector pension accounting, estimates the true debt burden is significantly higher than state estimates. Most recently, Moody’s pegged total state pension debt at $241 billion at the end of fiscal year 2018.3 That debt burden equaled more than 505% of annual state revenues, the worst pension debt-to-revenue ratio of any U.S state.4

Local government pension debt adds another $63 billion,5 bringing total state and local pension debt to more than $200 billion, according to official estimates. Moody’s does not provide independent estimates for all local systems.

Stock market losses related to the global coronavirus pandemic will cause those debt burdens to increase further and faster than previously expected. That’s because investment returns are a key source of pension fund income, accounting for 63% of revenue from 1989 to 2018 for all public plans nationally.6 The other two sources of public pension fund income are employee contributions and employer contributions, the latter of which means taxpayer contributions.

In Illinois, shortfalls in investment returns must be made up with higher taxpayer contributions in subsequent years. Employee contributions and benefits are both fixed by state law, meaning current system design requires no shared sacrifice from retirees or current workers to cover funding gaps.

More than 1 in 10 Illinoisans – 1.1 million, or about 11.4% of the adult population – are members of an Illinois public pension system.7

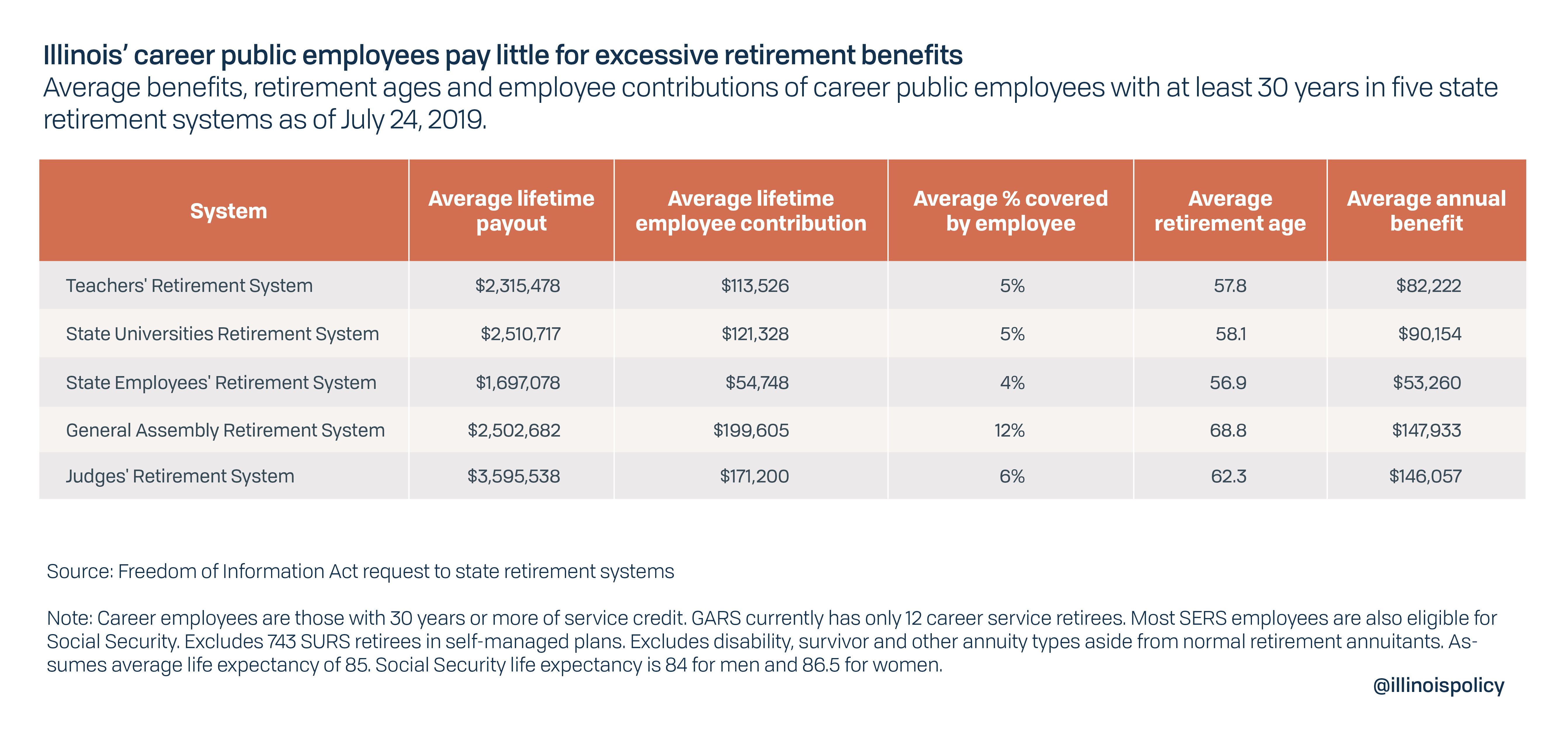

State worker contributions typically cover only about 4 to 6% of lifetime benefit payouts. The average lifetime payouts for members of the state retirement systems exceeds $1 million, and employees with 30 years of service or more can typically expect to collect more than $2 million. The only exception is for employees of state agencies and boards – nearly all of whom also qualify for Social Security – where the average benefit is a still generous $1.7 million even without Social Security payments factored in.

Ultimately, this flawed system design harms every resident in the state, including those relying on taxpayer-funded pensions for their retirement security. The financial burden it places on businesses and private sector workers is larger than they can bear, making the pension plans unaffordable and unsustainable in the long run. Eventually, the funds are likely to run out of money and be unable to pay promised annual benefits to retirees.

Even in the run-up to insolvency, public pension debt is already inflicting great harm on Illinois through higher taxes, fewer jobs, lower economic growth, residents moving out and cuts to public services that weaken the social safety net.

Pension costs are already eating away at Illinois government services. Pension costs increased by more than 500% during the past 20 years. Spending on core services, including child protection, state police and college money for poor students, dropped by nearly one-third since 2000.8 Pension contributions accounted for less than 4% of Illinois’ general funds budget from 1990 through 1997 but have grown to consume more than a quarter of the budget in recent years.9 That growth crowded out the state’s ability to spend money on programs that provide value to residents.

To avoid a future in which taxpayers are asked to pay ever more in taxes for fewer and fewer government services – while public servants are left with shaky retirement systems – Illinois must enact structural reforms as soon as possible to make pensions more resilient and affordable.

COVID-19 MARKET VOLATILITY THREATENS TO PUSH STATE PENSIONS OVER THE EDGE

Mary Williams Walsh, a New York Times reporter with experience covering bankruptcies in Puerto Rico and Detroit, wrote that “public pensions are the time bomb of government finances” in an article examining the impact of COVID-19 on pensions.10 In this unfortunately accurate analogy, that time bomb is also made of highly unstable nitroglycerin. Eventually, the bomb will explode, and the wrong shock threatens to set it off earlier than expected.

While this is a problem for many governments across the country, Illinois is home to the worst pensions crisis and faces the greatest risk.

Whether COVID-19 will trigger the inevitable explosion remains to be seen and will depend on how quickly financial markets are able to recover from the downturn. Regardless, the pandemic exposed the unacceptable fragility of many government pension systems and should serve as a wake-up call for elected officials.

Without transformative changes to pensions, a severe economic downturn will start a slide to insolvency and the potential collapse of government finances. This risk was apparent long before COVID-19.

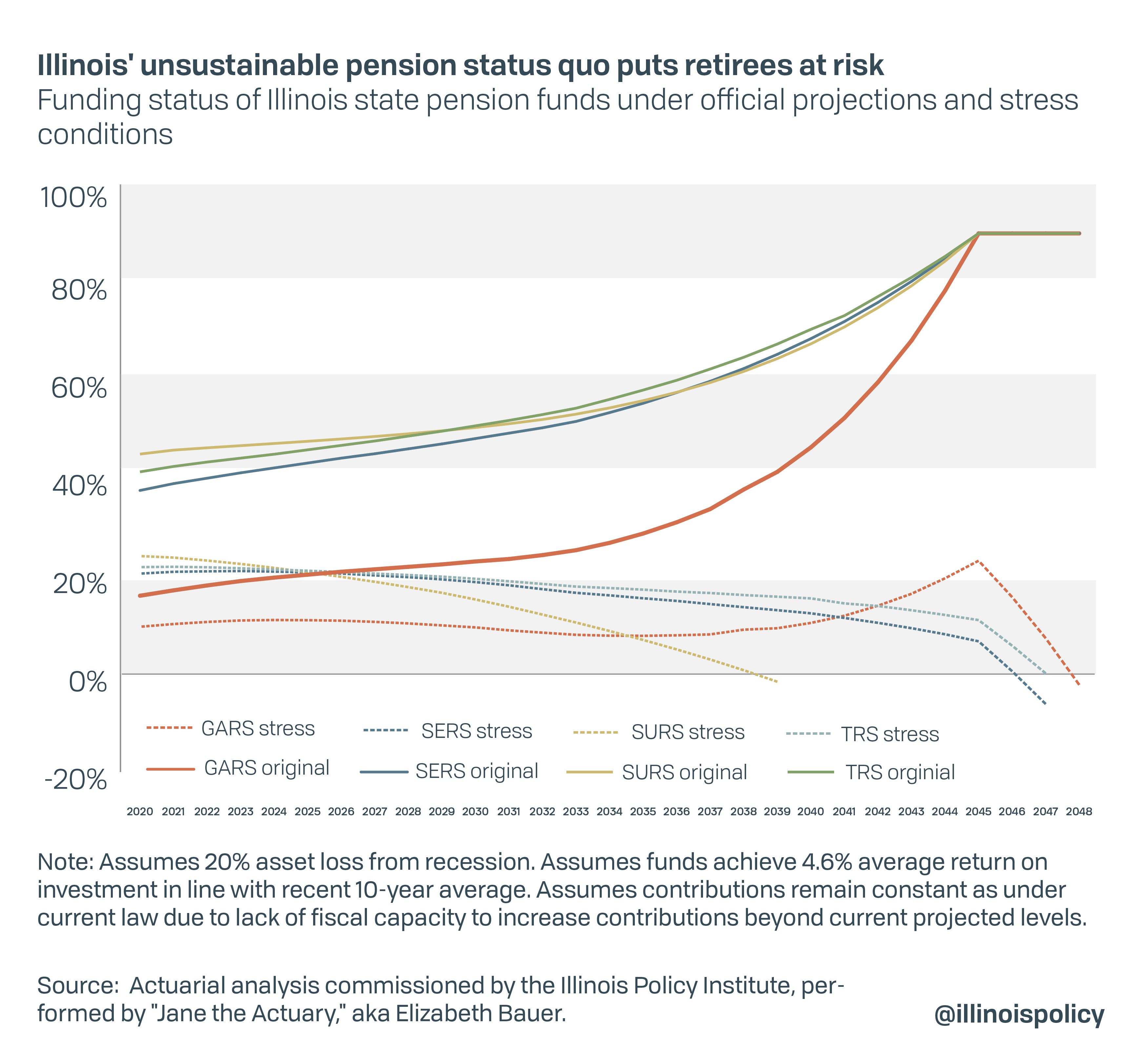

While the state’s official projections show all five state funds will reach 90% funding by 2045, this assumes the funds are able to obtain a consistent return on investment of between 6.5% and 7%.11 The state has regularly missed its investment return targets in the past, even when the economy was growing,12 demonstrating how unrealistic these assumptions have been.

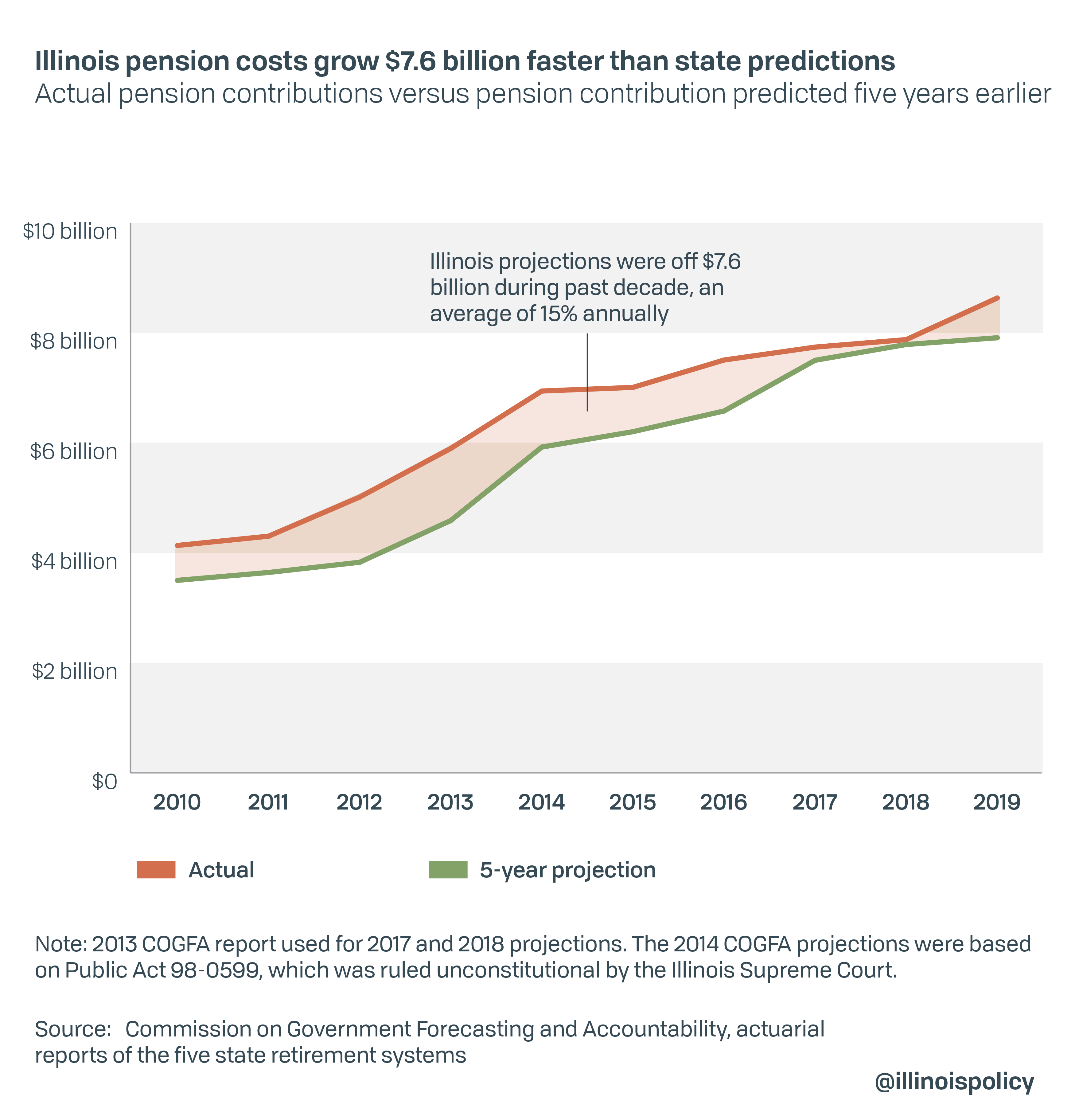

As a result of overly optimistic expectations for investment growth, taxpayer contributions to the systems have grown much faster than official projections suggested they would. From 2010 to 2019, taxpayers were forced to pay $7.6 billion more than the state estimated they would, compared to projections five years prior to each payment. On average, taxpayer costs were 15% higher than expected during the past decade.

But despite being asked to pay more each year and more than expected, taxpayers still cannot keep up with growing pension debt. A major hit to investments would start an inevitable slide to insolvency.

An actuarial stress test of the systems commissioned by the Illinois Policy Institute in fall 2019 shows if state-run pension funds lose 20% of their asset value as a result of a recession – the same loss experienced in 2009 – and the average return on investment matches the roughly 4.6% the funds experienced in the 10 years after the last recession,13 the state’s major retirement systems will run out of money in fewer than 30 years.

Under the stress test scenario, the State Universities Retirement System would be the first to reach insolvency, and by 2039, the fund would be unable to pay full benefits with assets on hand. The other systems would see their funding ratios – the amount of money on hand to pay promised benefits – decline each year despite constantly increasing employer contributions. Retirement systems for teachers, state employees and elected officials would run out of money between 2046 and 2048.

In the early days of the pandemic, the above scenario seemed poised to become reality.

Moody’s estimated on March 24 that if market losses continued along their downward trajectory at the time, the average pension fund would see annual asset losses of 21% in fiscal year 2020.14 The estimate is based on a representative sample of 56 large pension funds that account for roughly half of total U.S. pension assets and liabilities. Moody’s uses publicly available market indices that closely match the investment portfolio makeup of these funds to estimate losses in real time.

Unfortunately, most pension funds, including those in Illinois, do not supply even quarterly data on their investment performance. Actual annual results may not be available until December, months after the June 30 end of fiscal year 2020.

More dire predictions came from The Pew Charitable Trusts, which in a report April 24 estimated overall state pension debt would increase by $500 billion.15 That is a nearly 42% jump in one year.

However, market conditions have improved substantially since March. Pension investment losses will likely be less severe than Moody’s snapshot estimate. Using Moody’s same methodology, market indices point to an average loss of 0.13% as of the end of the fiscal year on June 30.16 But Illinois pensions will still almost certainly miss their optimistic target rates of return. This will drive debt and taxpayer contributions higher than pre-pandemic projections, though losses of this size are unlikely to trigger the total collapse that appeared possible in March.

Regardless of whether COVID-19 triggers the day of reckoning for Illinois pensions, it demonstrates how fragile the current system is. This should be used as an opportunity to fix the problem before it’s too late by building broad consensus around the need for reform.

Illinois’ pension status quo not only harms taxpayers and vulnerable state residents, but it also harms the state and local government employees relying on these systems for their retirement security. The Illinois Constitution’s pension clause has been interpreted as preventing any reduction in benefits, including future growth for work not yet performed. That strict reading will not matter if there’s no money.

Legal scholar and pensions expert Amy Monahan has argued even ironclad legal provisions preventing benefit cuts cannot be used to force states to pay full benefits if funds become insolvent.17 Simply put, if there’s no money, benefits can’t be paid without impairing the state’s ability to exercise the basic functions of government, and courts cannot force legislatures to spend money or incur debt.

LOCAL PENSION DEBT WILL CONTINUE TO DRIVE CITY SERVICE CUTS AND PROPERTY TAX HIKES

Pension debt poses financial risks to many Illinois cities at least as severe as the risk to the state – and in some cases worse. Mayors and other local elected leaders have been saddled with pension systems created by state law and have virtually no options to reduce costs or improve sustainability on their own.

Cook County Treasurer Maria Pappas told The New York Times that in the COVID-19 era, the condition of local pensions is “like a rubber band that’s been stretched too thin” and warned “the rubber band is about to break.”18 Local pension funds include eight Chicago funds, two for Cook County, the Illinois Municipal Retirement System, and nearly 650 police and firefighter systems for cities outside of Chicago.19

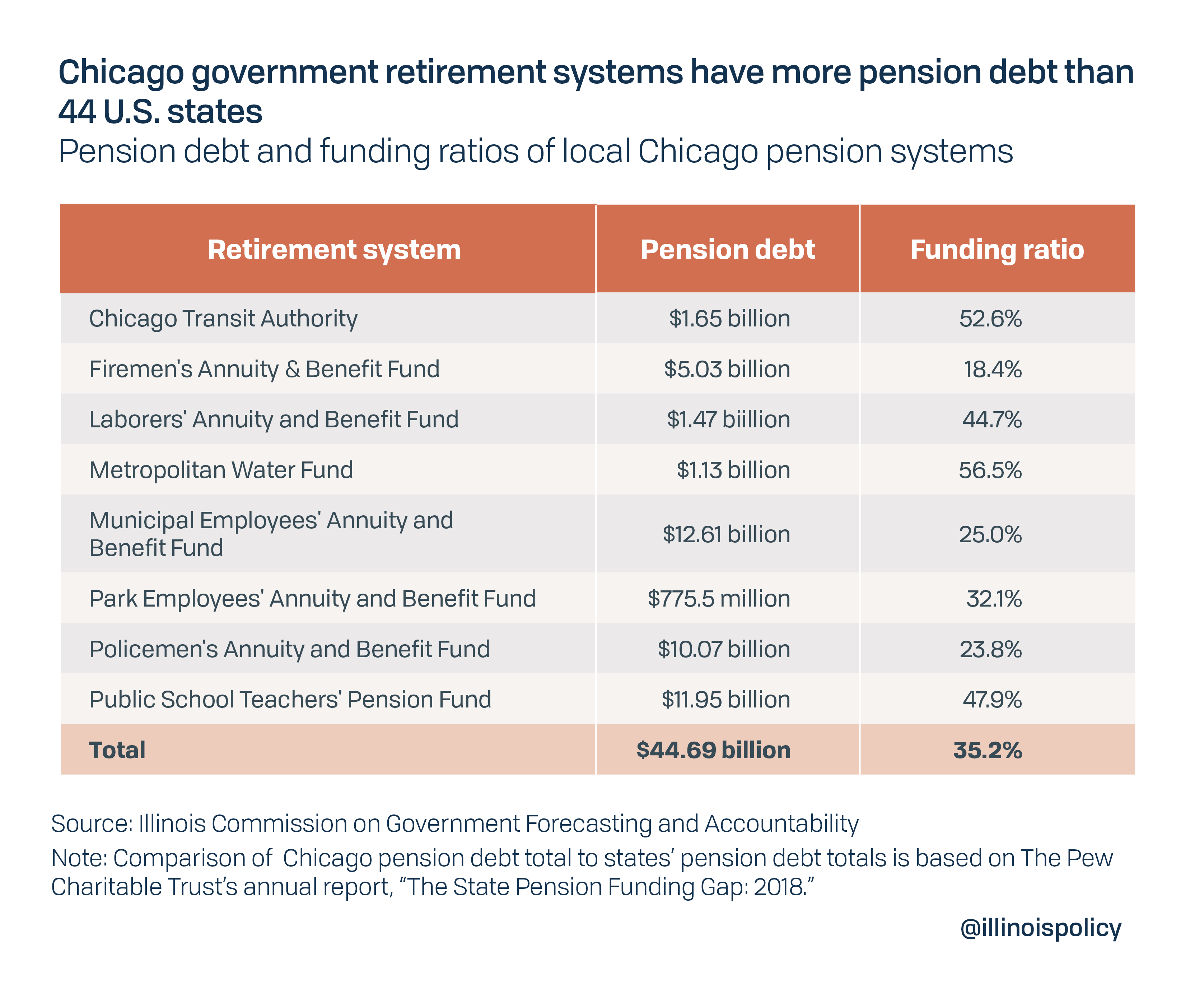

Chicago’s eight pension funds alone have more debt than 44 U.S. states, at more than $46 billion.20 Even before the pandemic, annual pension contributions from the city budget were expected to grow by $1 billion from budget year 2019 through 2023.21 Accounting for likely 2020 investment losses and the expected increase in taxpayer contributions, Chicago residents are likely to be hit with higher taxes, reduced city services or both to keep up with pension costs.

Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot has already made clear a property tax increase is on the table to deal with a city budget deficit of at least $700 million.22 Higher than expected pension contributions resulting from investment shortfalls make a significant property tax increase more likely.

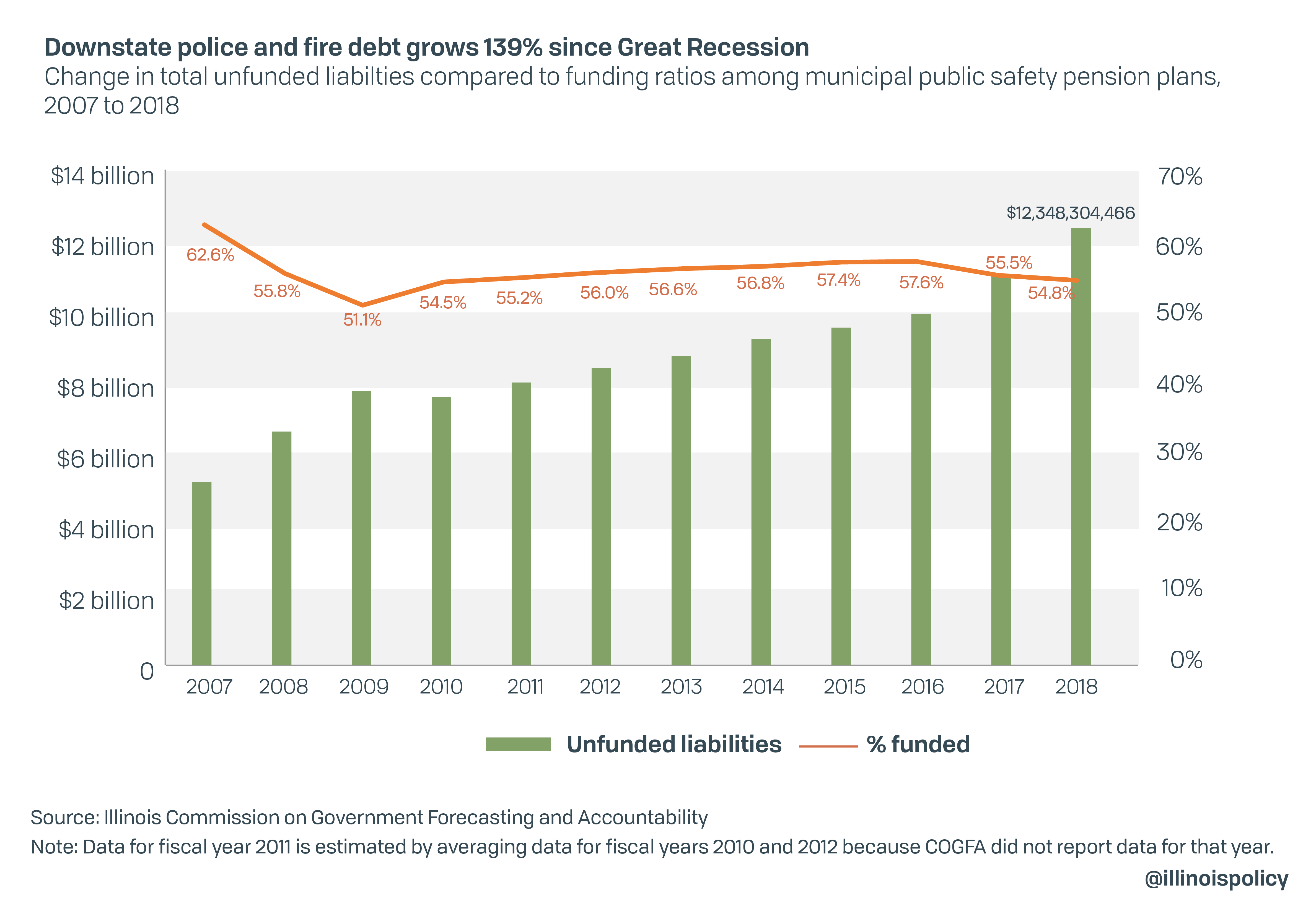

Many cities across the state face pension crises similar to Chicago’s. Unfunded pension liabilities in downstate public safety pension funds, which provide retirement benefits for municipal police officers and firefighters, have grown nearly 140% since before the 2008 financial crisis, ballooning to $12.3 billion in 2018 from $5.2 billion in 2007.

The overall public safety funding ratio has never recovered from the Great Recession, despite a decade of strong financial markets and economic growth. Illinois cities had only about 55 cents saved for every $1 in current and future pension benefit promises as of 2018, the most recent data available for all systems.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker and the Illinois General Assembly did take a small step toward addressing the rising debt and costs of local pensions in December 2019 by enacting a bill to consolidate the state’s nearly 650 public safety pension funds into just two, one each for police and firefighters.23 Combining small pension funds can help reduce administrative costs and enable higher investment returns because larger asset pools can generally diversify their investments more effectively and attract more professional investment managers.

However, a number of factors will limit the effectiveness of Pritzker’s pension consolidation measure.

First, the governor stopped short of proposing full-scale consolidation, electing instead to pool investment assets but leave in place various administrators for each local system. Failing to consolidate benefit administration means the state is forgoing $7 million in annual savings, according to a 2018 estimate from the Anderson Economic Group.24

Second, enhanced benefits for workers hired in 2011 or later were added into the pension consolidation bill late in the legislative process. While the task force created by Pritzker publicly claimed these benefit sweeteners would cost between $14 million and $19 million more per year – compared to their estimate of between $160 million and $288 million in higher returns – this was not based on any publicly available methodology or professional actuarial analysis.25 The benefits of consolidation could be wiped out if the cost of the pension sweeteners is higher than expected, as tends to be the case with official Illinois estimates for pension costs, or if estimates for additional investment revenues prove overly optimistic.

Lastly, the actual process of consolidating the funds is not expected to be completed until July 1, 2023.26 Downstate pension funds will not reap the benefits of pooling investment assets in time to help offset losses stemming from COVID-19.

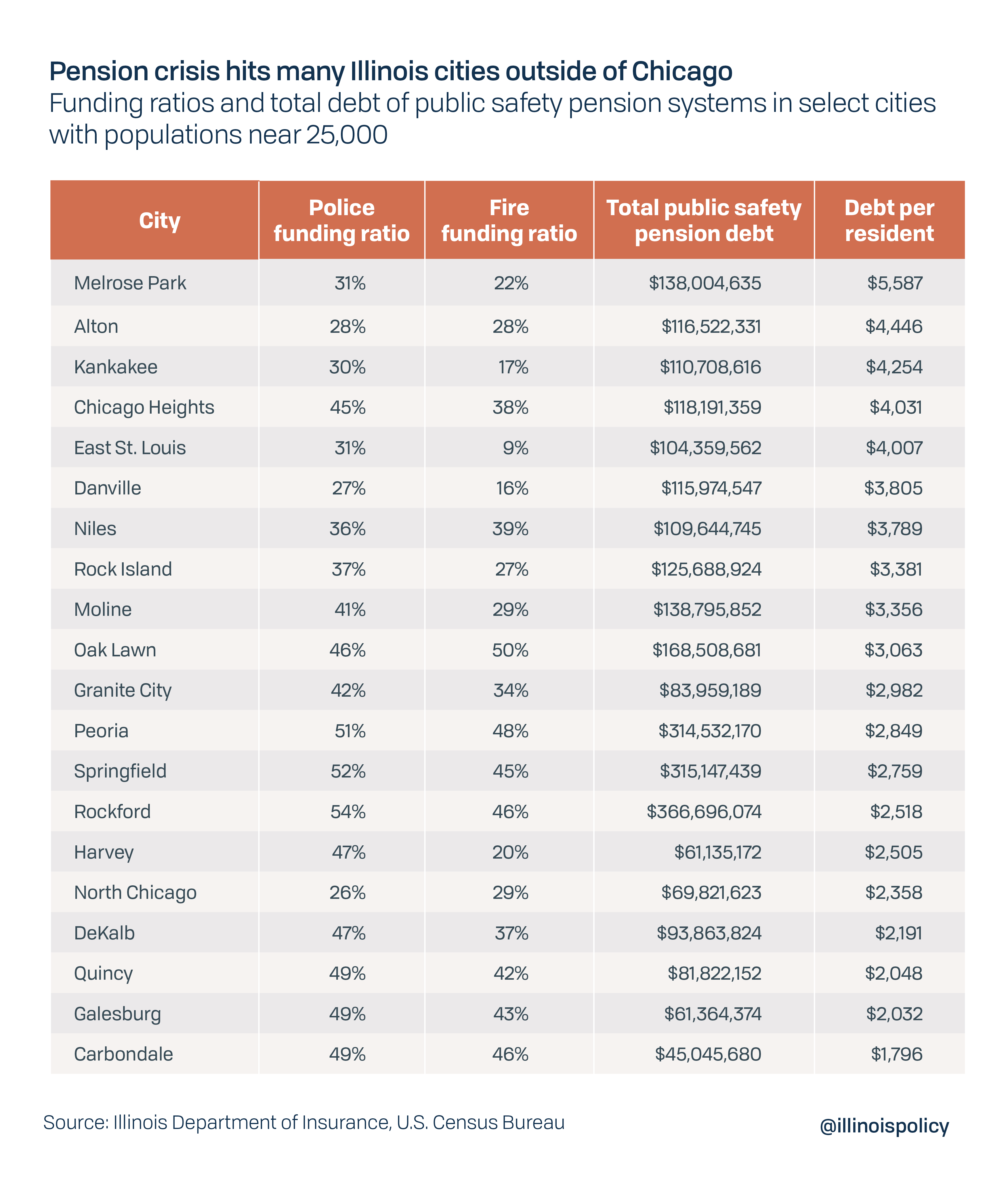

Mid-sized Illinois cities whose pension funds were troubled prior to the crisis will be at particular risk of service crowd-out and tax hikes going forward. Even after consolidation is complete, assets and debt for each pension fund will be accounted for separately and belong only to the corresponding local government. Generally speaking, a pension funding ratio of 60% or less means a plan is deeply troubled, while a funding ratio of 40% or less indicates a pension fund cannot recover without significant structural reforms. The 20 cities listed below represent deeply troubled pension funds in municipalities with populations of roughly 25,000 or more.

Pension debt per resident of these cities ranges from around $1,800 in Carbondale to nearly $5,600 in Melrose Park. That’s on top of $16,680 in state debt per person as of 2018, which translates to more than $44,000 per household.27 Each of these 20 troubled cities has at least one public safety pension fund with less than 50 cents saved for every $1 in future payouts. Such low funding ratios mean these funds are at risk of insolvency just like the state funds if a recession causes major asset losses.

Additionally, the losses caused by COVID-19 will almost certainly be worse for local public safety funds than for statewide funds. A report from Pritzker’s task force on fund consolidation compared average investment returns of downstate public safety funds to larger Illinois funds. From 2012 to 2016, downstate police and fire pension funds averaged a return of just 5.06% while all other funds averaged 6.89%.28 This gap means taxpayer costs will likely rise faster in local pension systems compared to the state funds, straining city budgets and potentially driving higher property taxes.

In recent years, many cities have already been forced to either lay off current workers, raise taxes or both to keep up with the cost of these pension systems. For example:

- Jerome,29 Geneseo,30 and Norridge31 raised property taxes to pay for pension costs in 2018.

- The south Chicago suburb of Harvey in 2018 laid off one-quarter of its police officers, more than half of its other police department personnel, and 40% of its firefighters after the state intercepted money bound for the city under a pension law intended to force cities to make required pension contributions.32

- In 2019, the pension intercept law was also triggered in North Chicago and East St. Louis.33 The resulting increase in pension costs for the cities’ budgets resulted in $1.3 million of cuts in North Chicago, including layoffs for three firefighters, and nine firefighter layoffs in East. St Louis.

- Peoria, which in 2018 eliminated 38 first responder jobs and 27 municipal jobs,34 has already been forced to cut an additional 45 jobs in 2020 after COVID-19 exacerbated the city’s pension-driven budget woes.35

CONCLUSION: REFORMING PENSIONS FOR RESILIENCY AND AFFORDABILITY WOULD BENEFIT EVERY ILLINOISAN

Illinois’ pension crisis is the most severe public policy issues facing the state. Pension debt can be directly linked to high taxes, reductions in government services, low home values and lagging economic growth. Market volatility linked to COVID-19 will exacerbate these problems and, by exposing the risk of total pension collapse, should be seen as an opportunity to build consensus for needed reforms.

However, the political hurdles to reform remain high. Amending the state constitution’s pension clause, a necessary first step for any successful reforms initiated at the state level, will require approval from three-fifths of both chambers of the Illinois General Assembly, along with supermajority ballot approval from voters in a general election. Building the required consensus for change will require political courage from lawmakers, honest dialogue with public employees whose long-term retirement security is at risk and widespread public acknowledgement of the problem.

For that to happen, politicians and residents will need to stop looking to false solutions that double down on past mistakes. Higher tax revenues are a self-defeating strategy in a high tax state that already spends more on pensions than anywhere else. Further tax hikes will only harm the state economy, preventing the sustainable growth in government revenues that comes from a prosperous private sector.

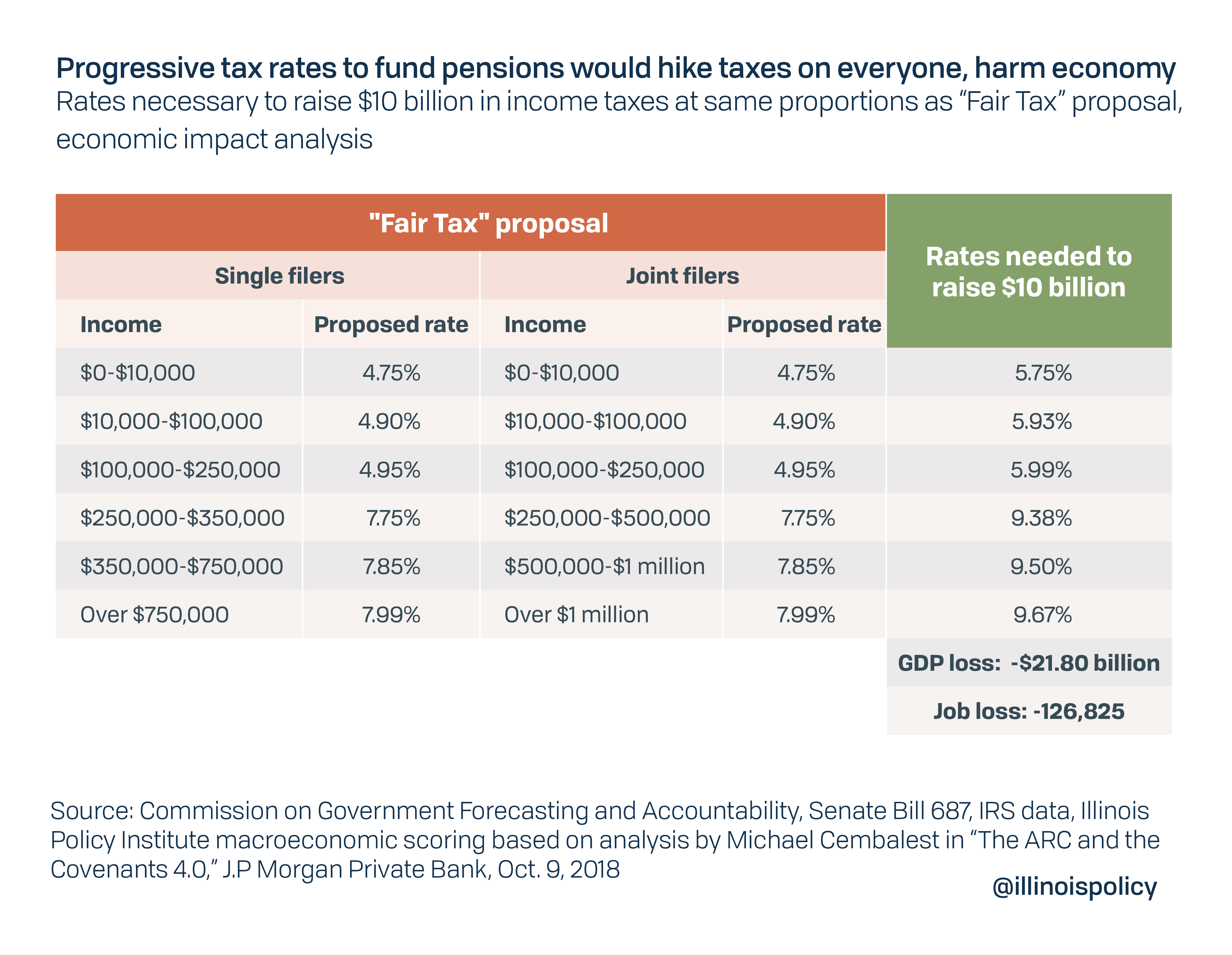

Pritzker’s proposed “fair tax” amendment – which would scrap the flat tax protection in the constitution in favor of a progressive tax system – cannot fix the pension crisis. The initial rates attached to his proposal would fall far short of the revenues needed to make a dent in the debt,37 making it highly likely that further tax increases are to follow if voters approve his plan in November.

A progressive tax hike that would actually raise enough money to pay off the pension debt, using the same bracket proportions as Pritzker’s initial rates, would have to raise taxes on all taxpayers by around 21%. A tax hike of this size would cost the state economy nearly 127,000 jobs and $21.8 billion in economic output.

There is a much better option available. Amending the constitution to allow for reductions in the future growth of pension liabilities, without taking away a single dollar of already earned benefits, could solve the problem in a way that’s fair and beneficial to every Illinoisan.

An actuarial analysis commissioned by the Illinois Policy Institute shows very modest reforms similar to those in a law passed in 2013 – before it was thrown out by the Illinois Supreme Court – can solve the pension crisis while leaving public workers with generous retirement benefits that are more secure than the status quo. Reforms that replace 3% compounding post-retirement raises with a true cost-of-living adjustment pegged to inflation, that slightly raise retirement ages for younger workers and that temporarily freeze annual benefit increases for some of the state’s largest pensions to bring them back in line with inflation can save the state more than $2 billion per year while fully eliminating the debt by 2045.38

COVID-19 was a dress rehearsal for the inevitable collapse of Illinois pensions in the absence of reform. Unfortunately, state elected leaders have no clear plan to prevent or manage this coming crisis. For the sake of all Illinoisans suffering under the broken status quo, it’s time to defuse the pension bomb before it’s too late.