Two decades of fiscal mismanagement left Illinois as one of the two states least prepared to weather a recession.

Now, with fallout from COVID-19 exposing that mismanagement, Illinois Senate President Don Harmon wants a federal bailout worth at least $44.2 billion.

Without strict consumer protections against risky bets, insider deals and other predatory behavior from state lawmakers, a bailout for Illinois or other states struggling with fiscal crises of their own making would be ineffective and harmful to residents already suffering under a broken system.

The terms of the deal

In a letter to Illinois members of Congress, Harmon requested:

- $15 billion from an unrestricted block grant

- A $10 billion pension bailout, structured either as a grant or a low-interest loan

- $6 billion to bolster the state’s unemployment insurance trust fund

- An increase in the portion of Medicaid paid for by the federal government to 65%, up from 50.96% in a typical year, worth an estimated $2.6 billion1

- $1 billion in health care grants to poor and minority communities

- $9.6 billion in direct aid to municipalities

So far, federal aid to states and local governments has been appropriately limited to disaster response efforts to fight the coronavirus pandemic – much as Congress would do for a hurricane or other natural disaster – or cash flow assistance through monetary policy.

Under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, the state of Illinois will receive more than $3.5 billion, along with $1.4 billion divided among Chicago and the five largest Illinois counties. Those grants can only be used for new costs directly related to COVID-19, not to make up for general budget holes or lost revenues.

The Federal Reserve has also set up a credit lifeline, essentially offering two-year loans to state and local governments, which can be used to cover gaps in operating budgets.

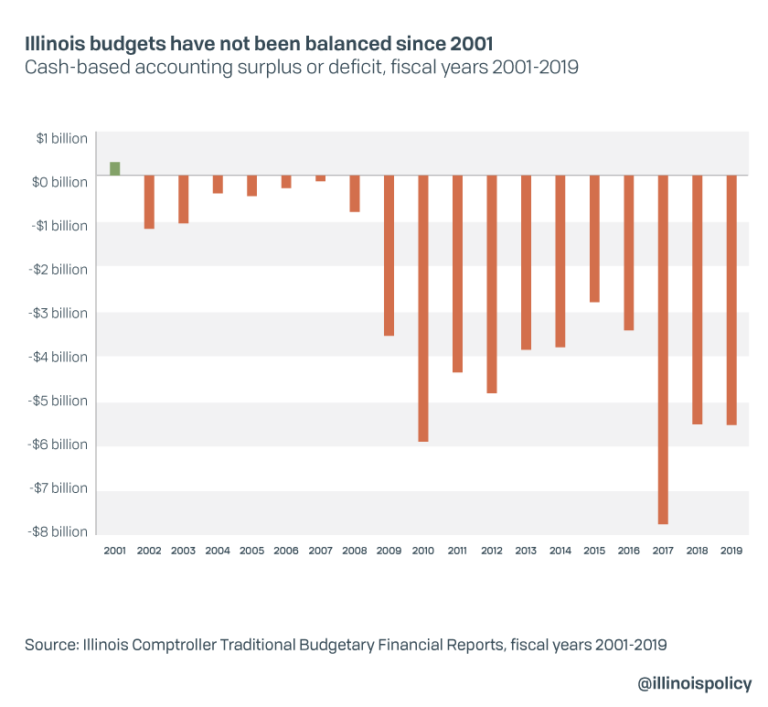

Much of Harmon’s request represents an entirely new category of federal help, going beyond disaster assistance by bailing Illinois out for mismanagement unrelated to the current public health crisis. The state’s near-junk credit rating, which reflects Illinois’ poor overall financial health, is a problem of its own making. Illinois has the worst pension debt among U.S. states and has not balanced a budget since fiscal year 2001.

While rejecting Harmon’s pension bailout idea publicly, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker has called for additional “unencumbered” funding from the federal government. Without clear restrictions, that money would inevitably flow to the state’s broken pension systems, including those of politicians who created the problem in the first place.

Any federal aid for pensions or to cover budget holes should be conditioned on significant financial reforms, including:

- A requirement that pension systems be built on sound funding plans with benefit structures that help protect taxpayers from risk, along with mandatory benefit reform in states where pension systems cannot be made solvent without increasing taxpayer costs.

- True balanced budget requirements and realistic accounting, ensuring state lawmakers cannot paper over deficits with accounting gimmicks or rack up excessive operating debt.

- Restrictions on when lawmakers can make withdrawals from rainy-day funds and procedures for making automatic deposits during growth years.

The only way to fix this problem is to demand any aid comes with rules that prevent dishonest accounting and reckless governance.

Illinois budget troubles stem from a pension crisis that bailouts can’t fix

For nearly two decades, Illinois politicians have spent more than the state brings in each year.

As a result of 18 consecutive years of unbalanced budgets, Illinois has the nation’s second worst net debt, measured compared to the size of each state’s economy. Debt per taxpayer equals $52,600, according to financial watchdog Truth in Accounting.

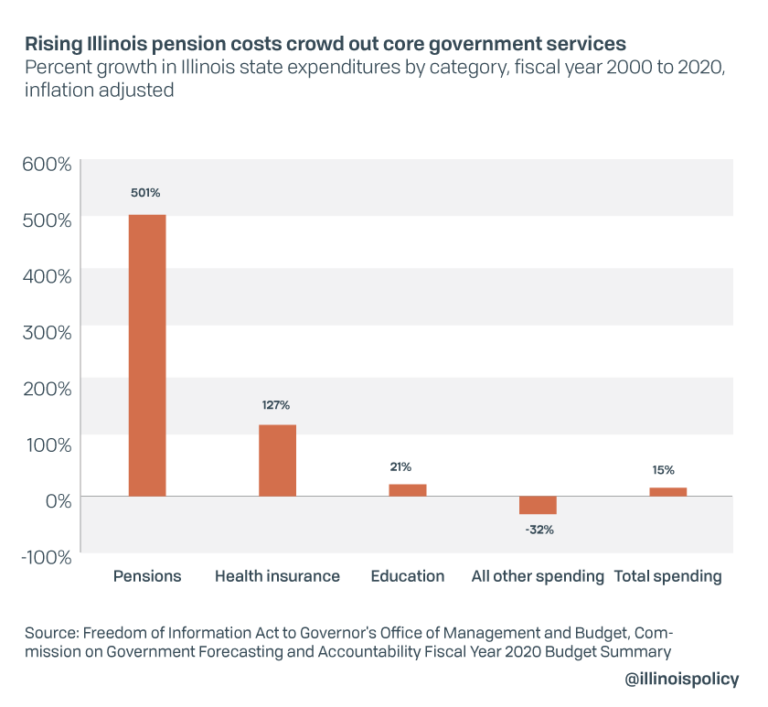

Springfield’s overspending has primarily gone to pay for pension benefits and state worker health insurance, while inflation-adjusted spending on a range of core government services has actually been reduced in real terms by nearly one-third. Yet despite the 501% increase in pension spending since fiscal year 2000, the five state pension systems have at least $138.6 billion in pension debt according to the state’s own estimates.

Illinois pension systems as they exist today are fundamentally unsustainable because benefits have been set at levels taxpayers cannot afford, and employee contributions set by state law are insufficient to cover a substantial enough portion of these benefits.

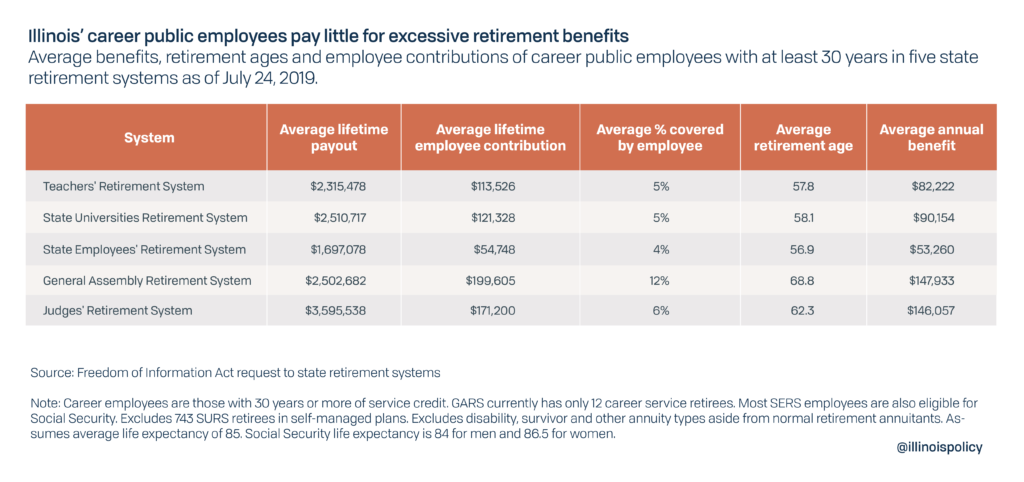

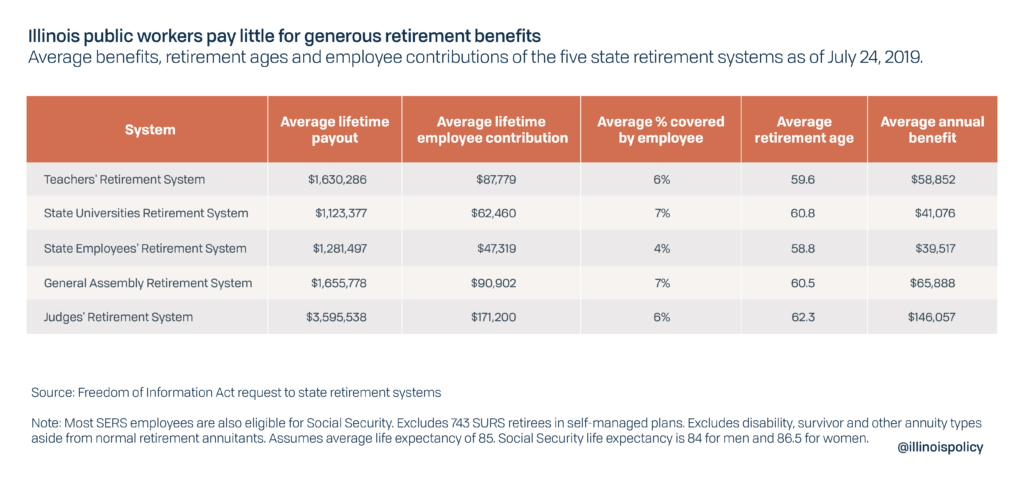

Career workers in the five state retirement systems, those with at least 30 years of service credit, contribute around 5% of what they receive in lifetime benefits on average. Among individuals relying solely on public pensions for retirement, total lifetime payouts range from an average as high as $3.6 million for career judges to $2.3 million for career teachers and education administrators. Career state workers receive lower lifetime benefits, a still generous $1.7 million on average, because more than 96% of them also qualify for Social Security.

Average benefits among all retirees, including those who worked the minimum number of years required to receive benefits, are somewhat lower. However, employee contributions still only account for between 4% and 7% of lifetime payouts when employees with fewer years of service are included.

Private sector taxpayers can rarely hope for the generous benefits they subsidize for public employees in Illinois. The typical private sector worker would need to have saved $1.6 million in a personal retirement account by age 60 to receive the same $82,000 base pension as the average career teacher. According to CNBC, the average 401(k) balance for those close to retirement, people aged 60 to 69, is just $195,500.

Tier 1 members of the state systems, those hired before January 2011, also receive 3% compounding post-retirement annual benefit increases, regardless of the actual rate of inflation or the health of the pension funds’ investments. Those guaranteed increases double the size of a retiree’s initial pension after 25 years. Such guaranteed increases are not an option for private sector retirees.

The General Assembly attempted to make modest changes to the future of pension benefits in 2013, including tying future annual benefit increases to inflation and slightly raising retirement ages for younger workers. These changes were struck down by the Illinois Supreme Court in 2015, which determined that even unearned future pension benefits were part of a contract that cannot be “diminished or impaired” under the pension clause of the state constitution.

Since the court’s ruling, Illinois’ elected leaders have made no substantive policy changes to fix the pension crisis, and the cost of pensions has continued to crowd out core services at the state and local levels. Pension costs have also contributed to pressures for income tax hikes at the state level and are the leading cause of local property tax bills being among the highest in the nation.

Despite tax increases and higher pension spending, public retirees’ benefits are still at heightened risk of insolvency due to economic fallout from COVID-19. Moody’s Investors Service estimates the average pension fund will lose 21.1% of its asset value this year. Given the state’s $96.6 billion in assets, that means the state could lose $20.4 billion. As the state’s total past and future pension promises will equal more than $242 billionfor fiscal year 2021, that would drop the pension funding from about 40% to 31%.

A stress test commissioned by the Illinois Policy Institute in fall 2019 found that a recession leading to a 20% loss of asset value in the pension systems could start a financial death spiral in the pension systems, with the State Universities Retirement System the first to run out of money in 2039.

Defenders of the current pension system sometimes claim pensions have simply been underfunded. But underfunding is a symptom, not a cause, of Illinois’ pension crisis.

While it’s true that politicians played reckless funding games and deferred costs into the future, this is the result of politicians having agreed to benefit levels that were too expensive to be affordable or sustainable. Because actually making the full payments would have been budget-busting and required unacceptably high taxes, both Republicans and Democrats at the state and local levels have historically sought creative ways to avoid making the full actuarial pension payments.

While Harmon’s letter claims the state is “on a path to fund the pension liability in a manner that is actuarially sound,” this is not true according to the state actuary, a pension watchdog within the Illinois Auditor General’s Office. Since the position was created in 2012, each annual report of the state actuary has warned that state pension funding policies don’t match generally accepted actuarial standards.

In other words, despite Illinois’ state and local governments spending the most in the nation on pensions as a percentage of their revenues, it still is not enough to keep the debt from growing under currently promised benefit levels.

Illinois’ worst-in-the-nation pension crisis cannot be fixed by throwing good money after bad. The requested $10 billion in aid for pensions would merely give Springfield politicians an excuse to put off needed reforms a little longer. To be effective, aid must come with structural reforms to make Illinois pension benefits sustainable and affordable for taxpayers.

If the federal government plays any role in helping Illinois fix its self-made pension and budget troubles, that role cannot be to simply prop up state politicians’ fiscal mismanagement, or it will fail to solve the problem while also wasting money collected from taxpayers around the nation.

Congress must attach strict consumer protections to any future financial aid

On top of an overpromised and mismanaged pension system, Illinois is home to a number of bad budget practices and lacks fiscal constraints that commonly protect taxpayers in other states. An Illinois Policy Institute report, “Bad budgeting basics: How Illinois’ budget process hurts taxpayers,” explains how many of the state’s budget and accounting practices have enabled or encouraged fiscal mismanagement in Springfield.

Among the findings in that report are the following:

- Illinois ranked 45th among U.S. states for rainy-day fund reserves from 2005 to 2018, saving just 0.8% of its budget compared to an average of 4.6% for all states. Experts generally recommend states hold 5-10% of annual revenues in reserve to prevent policymakers from having to rely on severe service cuts or tax hikes during recessions and disasters.

- From 2003 to 2017 the state budget included nearly $38 billion in inadvisable budget maneuvers, each year relying on one-time revenue infusions from borrowing and special funds transfers to cover operating deficits.

- Illinois is one of just 11 U.S. states which lacks a “true” balanced budget requirement, in which revenues and expenditures must actually balance at the end of the fiscal year rather than just in lawmakers’ projections.

Many states have spent the past decade of economic growth setting aside reserves for the next recession. The median rainy day fund balance among states prior to the pandemic was 8% of general revenues, according to the Tax Foundation. Unfortunately, Illinois has continued to overspend and dip into its reserves over the past two years; it has essentially nothing set aside to cover revenue losses on its own.

Worse, Illinois actually carries what is essentially a perpetual operating deficit through its backlog of unpaid bills. As of April 21, Illinois owes more than $8 billion to various vendors for services already rendered. Under state law, the unpaid bills carry high interest penalties ranging from 9% to 12%. The state’s weak and ineffective balanced budget requirement allows the backlog deficit to be carried from year to year.

The bill backlog more or less amounts to a negative balance in the rainy day fund, equivalent to an individual who not only has no savings account but is carrying thousands of dollars in high interest credit card debt.

So long as these bad budgeting practices remain in place, federal taxpayers cannot trust Illinois to be an effective steward of additional tax dollars.

If the federal government is to offer aid to troubled states for lost revenue or mismanaged pensions, it should impose the following conditions:

- Sound pensions with taxpayer protections: Pension funding should be based on actuarial best practices, with funding plans on track to fully eliminate pension debt over no more than 25 years. The federal government should require that annual cost of living adjustments, COLAs, are variable with either inflation or the rate of return on pension fund investments. Finally, if any state cannot achieve actuarial funding in 25 years without increasing taxpayer costs, their pension liabilities should be reduced to the level taxpayers can afford through either state-based reforms or a federally managed process.

- Truly balanced budgets and realistic accounting: All states receiving federal aid should be required to maintain end-of-year “true” balanced budgets. A proposal from the Illinois Policy Institute would require truly balanced budgets by prohibiting deficits from being carried over, while also clarifying that the state cannot count one-time budget gimmicks toward its revenues for the sake of balancing.

- Rainy-day fund protections: To ensure the federal government will not need to continue bailing out mismanaged states, each state should be required to set up a system ensuring it has a sufficient rainy-day fund in the future. First, states should be required to make automatic deposits to rainy day funds during growth years, until the balance equals 10% of annual revenues. States with negative operating reserves, such as Illinois, should be required to set aside a portion of annual revenues and create a payment plan to eliminate their carried deficits. Finally, withdrawals from the rainy-day fund should be legally permissible only when an economic downturn or emergency strikes.

Conditioning financial aid on consumer or taxpayer protections is a common practice to safeguard funds flowing to troubled entities.

Financial rescues in both Greece and Puerto Rico came with conditions and oversight boards. Corporate assistance under the CARES Act likewise imposed restrictions, limiting stock buybacks and executive compensation, among other conditions.

To ensure financial mismanagement does not continue, Congress should not bail out Illinois or other troubled states without significant consumer protections and financial reforms.