Illinois’ pension crisis is the worst in U.S. history – which begs the question, “Why?”

First, because public employees pay very little toward their own retirement and assume none of the economic risk for investments. Second, because workers retire relatively young so they are drawing from the systems longer. And third, because they receive pension benefits often in excess of $2 million during the course of their long, generous retirements.

Ultimately, this poorly designed system is bad for the retirees. They face a serious risk that the pension systems will go insolvent.

The state has five retirement systems it manages directly and is responsible for contributing to:

- The Teachers’ Retirement System, or TRS, for pre-K through 12th-grade school employees outside of Chicago

- The State Universities Retirement System, or SURS, for higher education employees

- The State Employees’ Retirement System, or SERS, for employees of state agencies and boards

- The Judges’ Retirement System, or JRS, for judges

- And the General Assembly Retirement System, or GARS, which manages pensions for state lawmakers and statewide elected officials

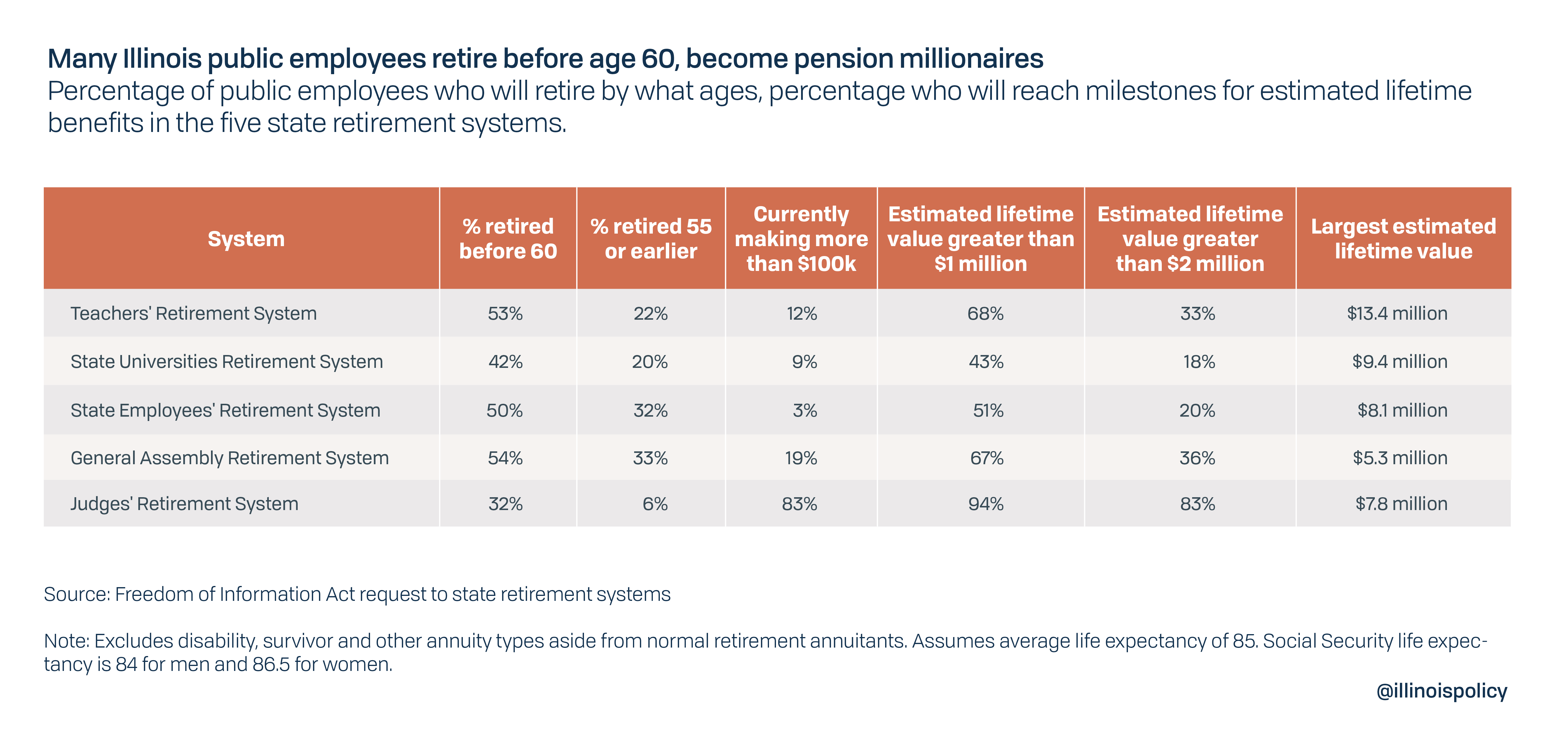

More than 50% of state workers and teachers will retire before age 60. Taking advantage of early retirement benefits, large portions of these employees will retire prior to age 55.

These returns on retirement investments combined with early retirement is unheard of in the private sector.

The average Social Security benefit for 2019 is $17,532 per year. The maximum Social Security benefit is $34,332 per year. The earliest anyone can qualify for Social Security is age 62 and the full retirement age for anyone born after 1960 is 67. According to CNBC, the average 401(k) balance for those close to retirement, people aged 60 to 69, is just $195,500. However, with prudent savings and an early start, personal retirement accounts can be a secure way to fund retirement. Fidelity Investments reported in 2018 that the number of 401(k) and IRA millionaires was at an all-time high – up 41% from just one year earlier.

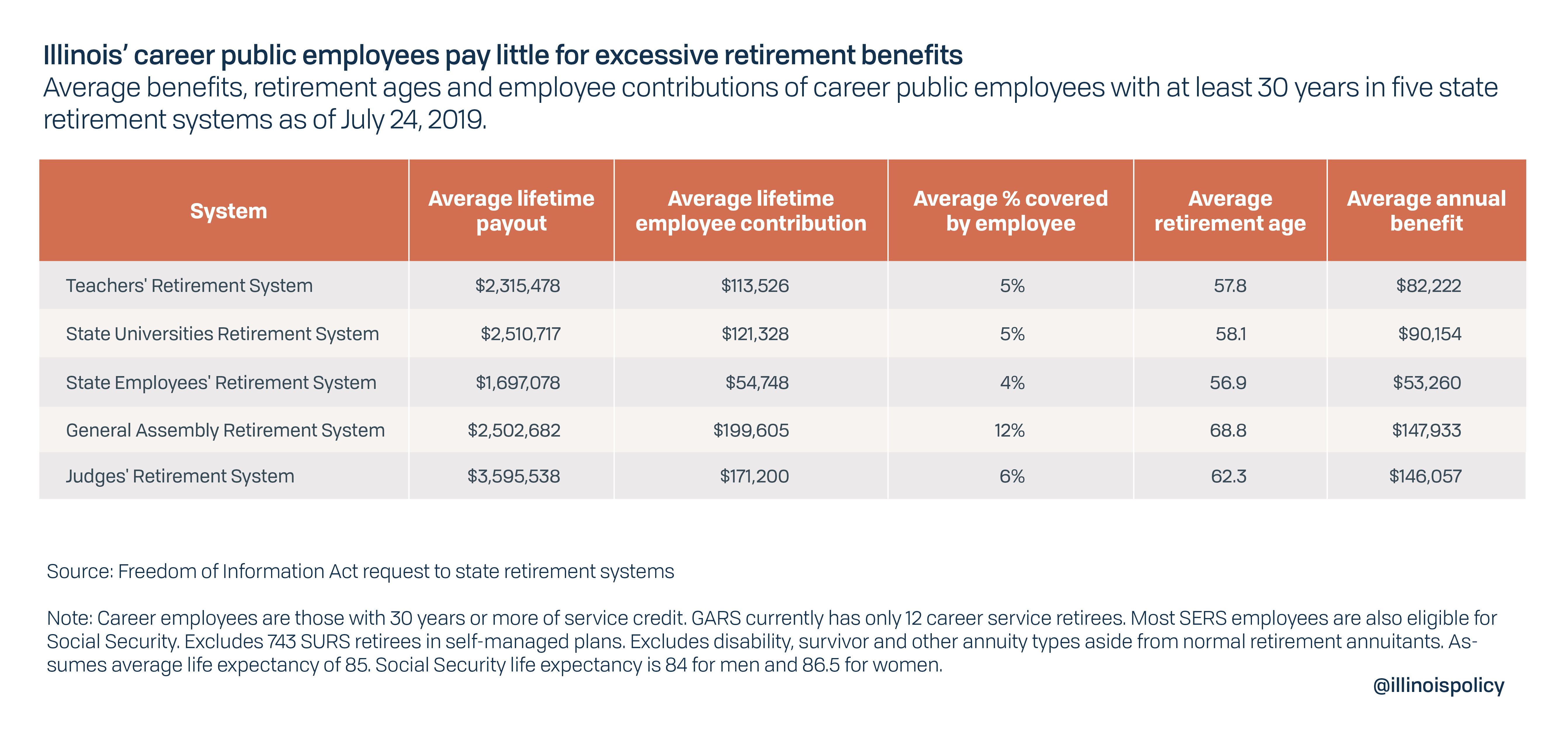

No matter how you look at it, private sector taxpayers can rarely hope for the generous benefits they subsidize for public employees. The typical private sector worker would need to have saved $1.6 million in a personal retirement account by age 60 to receive the same $82,000 base pension as the average career teacher, or those with at least 30 years of experience. And 3% compounding post-retirement increases are not an option for private sector retirees.

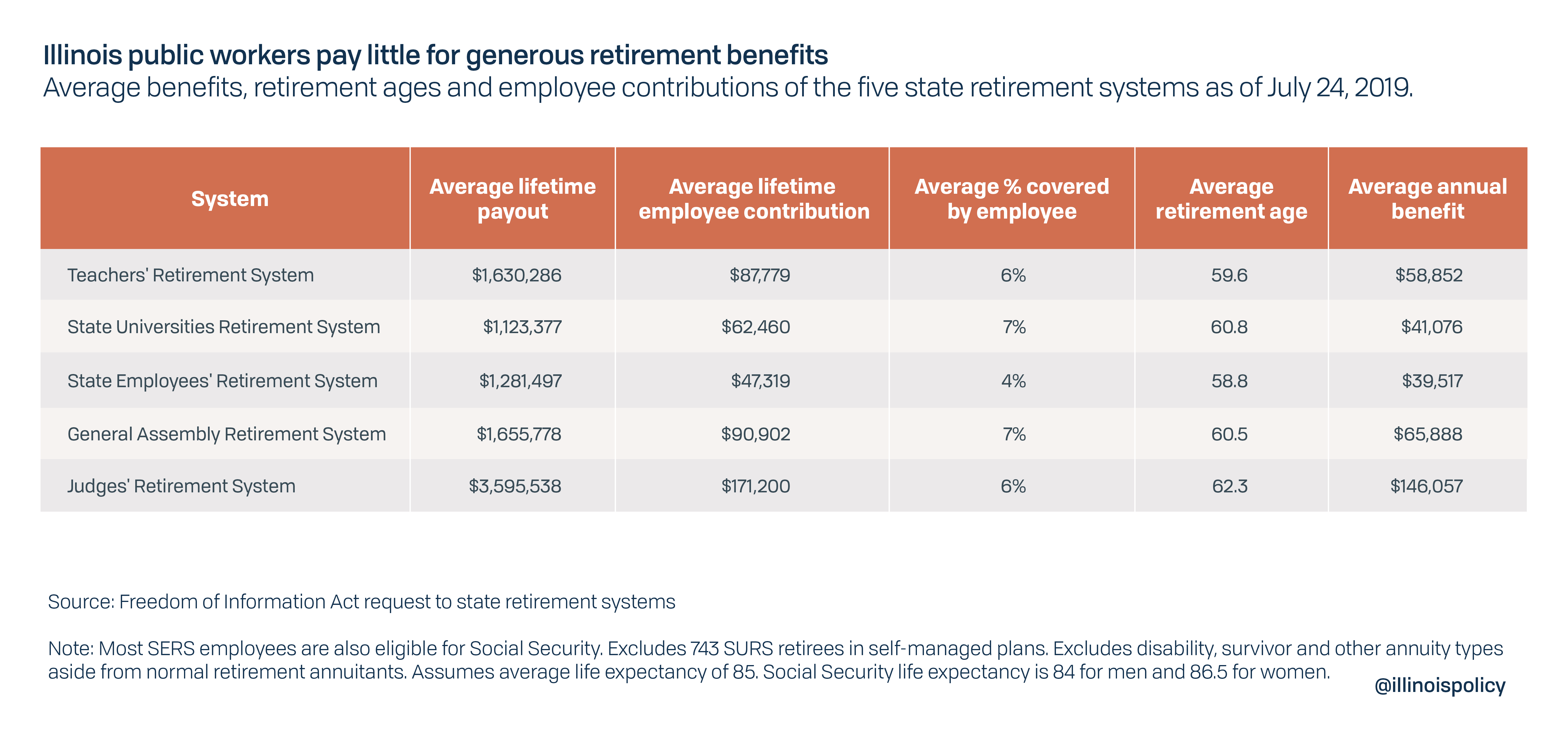

Illinois law requires public employees to set aside very little on their own during a typical working career. This is especially true for “career employees” with at least 30 years of service credit but applies to shorter-term public workers as well.

While benefit payments are lower for employees in TRS, SURS, SERS and JRS who do not work at least 30 years, the benefits are still substantial. Illinois taxpayers subsidize the majority of the cost and assume all the risk without the ability to modify even future promises.

For career workers who serve 30 years or more, lifetime employee pension contributions account for between 4% and 6% of expected payouts, other than for members of the General Assembly Retirement System. These contributions legally guarantee employees a pension that is typically worth more than $2 million. State employees in SERS are the exception, but they are generally eligible for Social Security benefits and still average a generous $1.7 million. As of the most recent report from the state, 96.3% of state workers are also eligible for Social Security, which explains the somewhat lower benefit.

The state implemented a less generous benefit schedule for employees hired after Dec. 31, 2010, but the first so-called “Tier 2” employee will not be eligible for retirement until January 2021 because they must be at least 67 years old with 10 years of service to qualify for a pension.

Illinois pension debt exists almost entirely because of benefits for Tier 1 workers and retirees, those who began working for an eligible government employer prior to 2011. In fact, younger workers in Tier 2 may actually be subsidizing Tier 1 benefits by paying in more than they’ll receive, at least for teachers. As a result, teacher advocacy groups have predicted that if the state does not fix Tier 2 benefits, a lawsuit against the state is likely which could force higher benefits and increase the state’s pension debt even further.

Lawmakers did recently enhance benefits for Tier 2 downstate public safety workers. But they did so without knowing the cost or determining that it was actually necessary.

Still, the state’s $137 billion to $234 billion in public pension debt is really about Tier 1 workers and retirees.

All Tier 1 retirees in the five state systems receive a 3% compounding annual increase regardless of actual inflation. While often mistakenly referred to as a “cost of living adjustment,” these are more accurately described as guaranteed post-retirement raises because they are not pegged to inflation.

Weren’t Illinois pensions underfunded?

One common call among government worker unions and associated advocacy groups is that Illinois pensions were not overpromised, but underfunded.

While it’s true Illinois politicians played reckless funding games, this is a symptom that benefits were set at a level that was too expensive to be affordable or sustainable. Because actually making the full payments would have been budget-busting and caused unacceptably high tax levels, both Republican and Democrats at the state and local levels have sought creative ways to avoid making the full actuarial pension payments over the years.

- Republican former Gov. Jim Edgar negotiated a payment ramp with the General Assembly that violated actuarial best practices of funding. First, the payments were stretched out over 50 years while actuaries typically recommend 20-year payment schedules and no more than 30. In practice, this means payments were low during Edgar’s term and spiked dramatically for his successors. Second, the funding target was set at 90% rather than 100%, meaning the state’s current funding plan does not fully anticipate paying off the debt.

- Democratic former Gov. Rod Blagojevich issued bonds to pay off part of the pension debt but then used those proceeds as an excuse to reduce the state’s regular pension contributions from the operating budget. At the time, this “pension holiday” was supported by several of the state’s politically active public sector unions, including the Service Employees International Union, the Illinois Federation of Teachers and the Illinois Education Association.

- Due to the lack of a funding requirement from the state, local mayors have regularly shorted their contributions to downstate police and fire pension funds in cities across Illinois. Pension benefits for local governments are established by state law. In other words, mayors were struggling to manage their own budgets and provide services without an unreasonable tax burden while being forced to pay for unsustainable pension benefits they played little to no role in creating. Now that the state is enforcing full required payments, local mayors in several towns have been forced to lay off police officers and firefighters or otherwise cut municipal services to pay for pensions.

State and local governments in Illinois already spend the most in the nation on pensions as both a percentage of their total revenues – about double the national average – and compared to the size of the state’s economy. Illinois pension debt is equal to roughly one-third of everything the state’s businesses and residents produce in a year.

Illinois’ ever-growing pension spending is already crowding out core government services. The state spends about one-third less today, adjusted for inflation, than it did in the year 2000 on core services including child protection, state police and college money for poor students. During that time pension spending increased 501%.

Despite these facts, some opponents of pension reform have maintained that “underfunding” of the pension systems is a chief cause of the debt. In a very narrow financial sense, this might be true. The existence of any form of debt is proof that not enough money has been set aside.

But in terms of the conclusions drawn by pension reform opponents, nothing could be further from the truth than the idea Illinois has a pension crisis because taxpayers haven’t been paying enough. They already pay the most and would have to double the amount they’re paying to eliminate the debt.

To show just how absurd the “underfunding” argument really is, imagine you took out a $1 million mortgage on a $40,000 annual income.

Your monthly mortgage payment — not including property taxes — would total $3,800 using today’s standard interest rate. Problem is, your monthly take-home pay — after accounting for state and local taxes — is about $2,650.

As much as you wanted that house, you never would have been able to afford that monthly cost, given your ability to pay. Before long, the bank will come knocking to repossess the property.

You may have “underfunded” your mortgage, but only because you originally overpromised on what you would be able to pay. Similarly, Illinois politicians promised pension benefits that taxpayers never could and never would be able to afford. They designed a system with no flexibility or risk sharing, placing all the burden on taxpayers to make up for the shortfalls of their mismanagement.

Illinois pensions were underfunded because they were overpromised. Rather than dealing with the painful tax hikes necessary to fully fund exorbitant benefits, politicians racked up debt, placing the burden of pension funding on the state’s young and unborn.

Regardless, it’s clear that tax hikes are not a potential solution going forward.

Those who deny the extravagance of current Illinois pension benefits also elude a key question: What next? To catch up the states’ five pension systems, Illinois median income family would have to see a tax hike of about $1,800, per year.

Is there any way out of Illinois’ pension crisis?

Tax hikes are not a responsible or realistic solution to the worst pension crisis in the nation. Illinois’ tax burden is already one of the nation’s most painful and the top reason residents cite for wanting to leave the state.

Illinois could file for bankruptcy protection under hypothetical legislation similar to the “PROMESA” law Congress passed to deal with Puerto Rico’s financial distress, but that scenario is extreme and unlikely. The state’s only viable option is meaningful pension reform. That starts with a constitutional amendment to allow changes to unearned, future benefits.

Rather than deleting the pension protection clause entirely, Illinois should seek to modify it to match states such as Hawaii or Michigan which protect only “accrued benefits.” Subsequent pension reforms should include raising retirement ages for younger workers, capping maximum pensionable salaries, and doing away with guaranteed permanent benefit increases in favor of a true cost-of-living adjustment pegged to inflation.

An actuarial analysis, performed by a certified professional actuary and commissioned by the Illinois Policy Institute, shows that reform to unearned future benefits could save roughly $2 billion per year in pension contributions and fully eliminate the debt by 2045. From now until 2045, total savings would be $50.92 billion. That’s all possible without taking away a single dollar earned to date.

The concept of future benefit reforms has been successfully enacted in Colorado as well as in Arizona, which had support from union leaders who realized pensions were in peril.

Pension reform is a moral imperative. The alternative is a future in which core services are cut, taxes are raised on a dwindling number of taxpayers and pensioners risk losing what they’ve already been promised as the funds go insolvent.

If Illinoisans work together, common-sense pension reform can work for everyone.