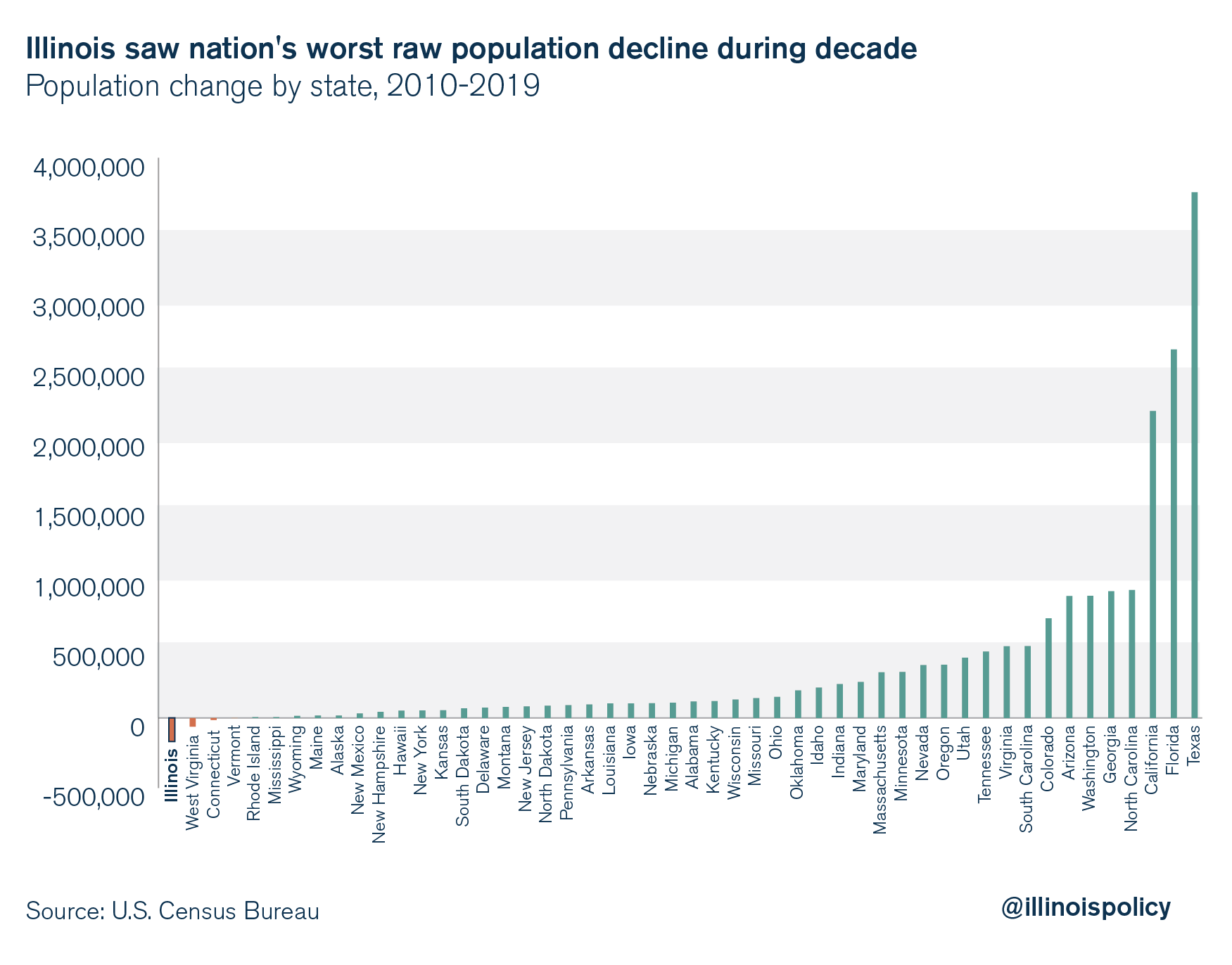

The 2010s were a lost decade for the Land of Lincoln, which shed more people than any other state in the nation.

Data released by the U.S. Census Bureau Dec. 30 show Illinois’ population dropped by 168,700 people from 2010-2019, the largest raw decline of any state and more than the entire population of Naperville, Illinois’ third-largest city.

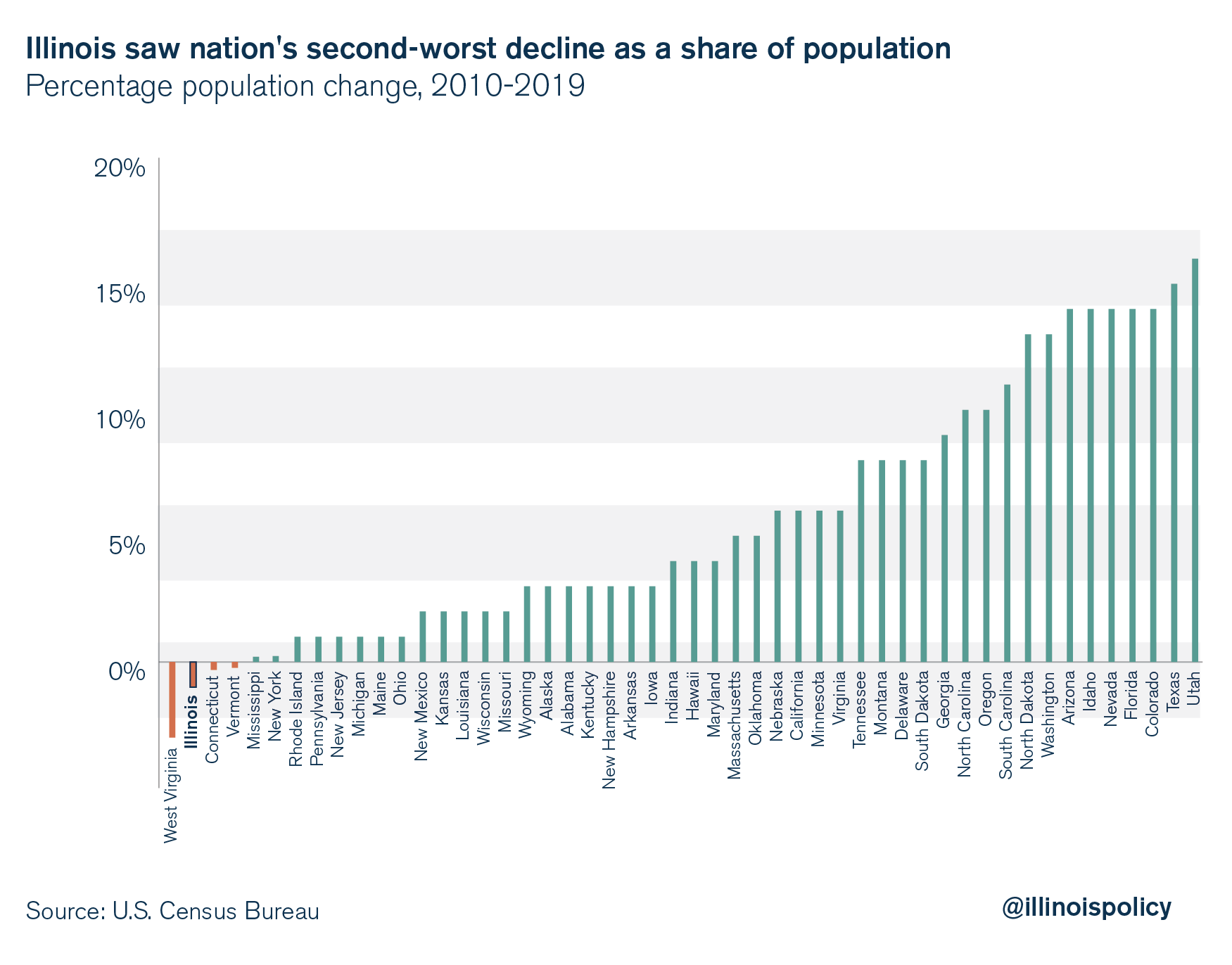

In percentage terms, this drop was second only to beleaguered West Virginia during the decade.

That population decline, especially the loss of prime working-age adults, causes serious economic harm for Illinoisans who remain in the state.

If Illinois had simply kept pace with the average state population growth since the start of the Great Recession in 2007, when Illinois’ labor force was at its peak, the state’s population would be 1.14 million residents, or 9%, larger than it is today. This increase in population would yield an economy that is at least an estimated $78 billion larger than today, equivalent to the entire state economy of Delaware.

It would also pad state coffers without tax hikes, increasing Illinois’ General Revenue Fund by an estimated $3.45 billion, compared with today.

That’s more than the generous estimate of $3.4 billion in new revenue Gov. J.B. Pritzker predicts his controversial progressive state income tax hike would generate. Illinois voters will decide the fate of Pritzker’s plan at the ballot box Nov. 3, 2020.

Population decline continues in 2019

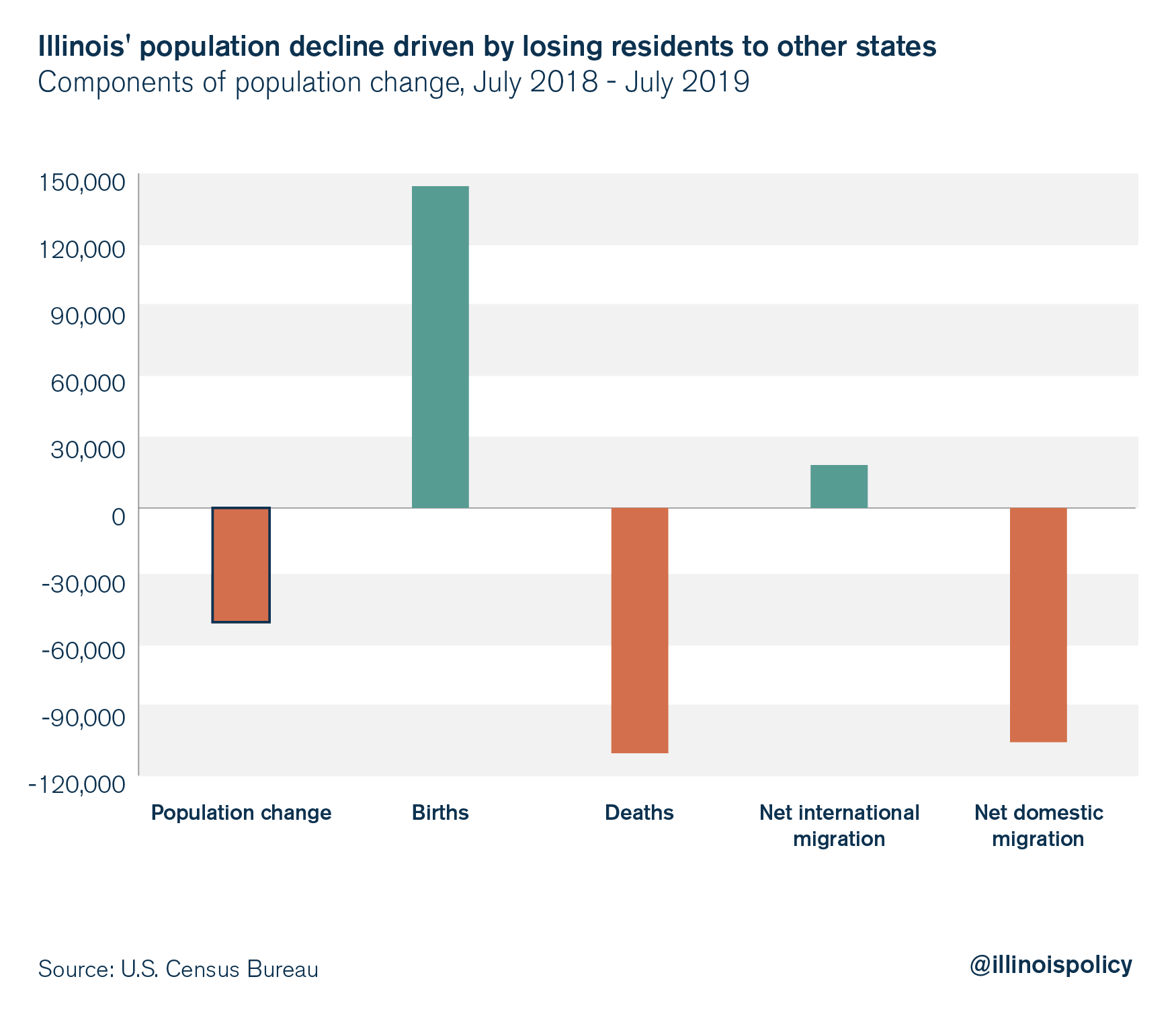

From July 2018 to July 2019, Illinois’ population shrank by 51,250, the second-largest raw decline in the nation behind New York and the third largest in percentage terms behind West Virginia and Alaska, according the Census Bureau.

The largest driver of Illinois’ population decline? More people are leaving for other states than arriving from other states. During the year, Illinois lost 104,986 people on net to other states, or roughly 288 residents per day. That’s one person every 5 minutes.

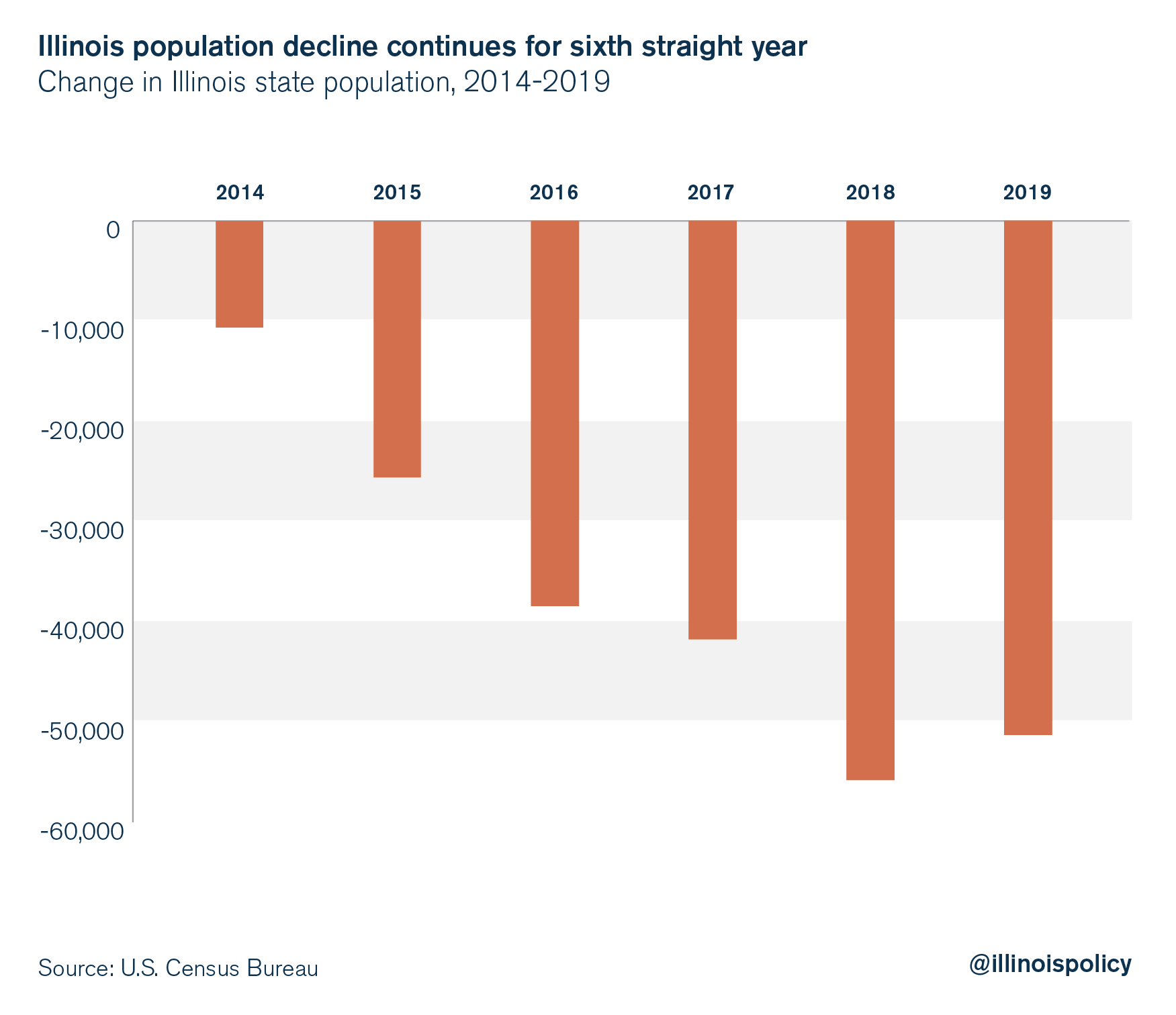

Population decline reached record levels in 2018, the year after the Illinois General Assembly passed the largest permanent income tax hike in state history, while population decline in the second year of the tax increase continued at a faster rate than before the tax increase. This result comes as no surprise as the 2017 tax hike has likely deterred new investment and job creation, making Illinois a less promising state in which to find opportunity.

This was Illinois 6th consecutive year of population decline. Among all 50 states, only West Virginia has experienced more consecutive years of population decline with seven.

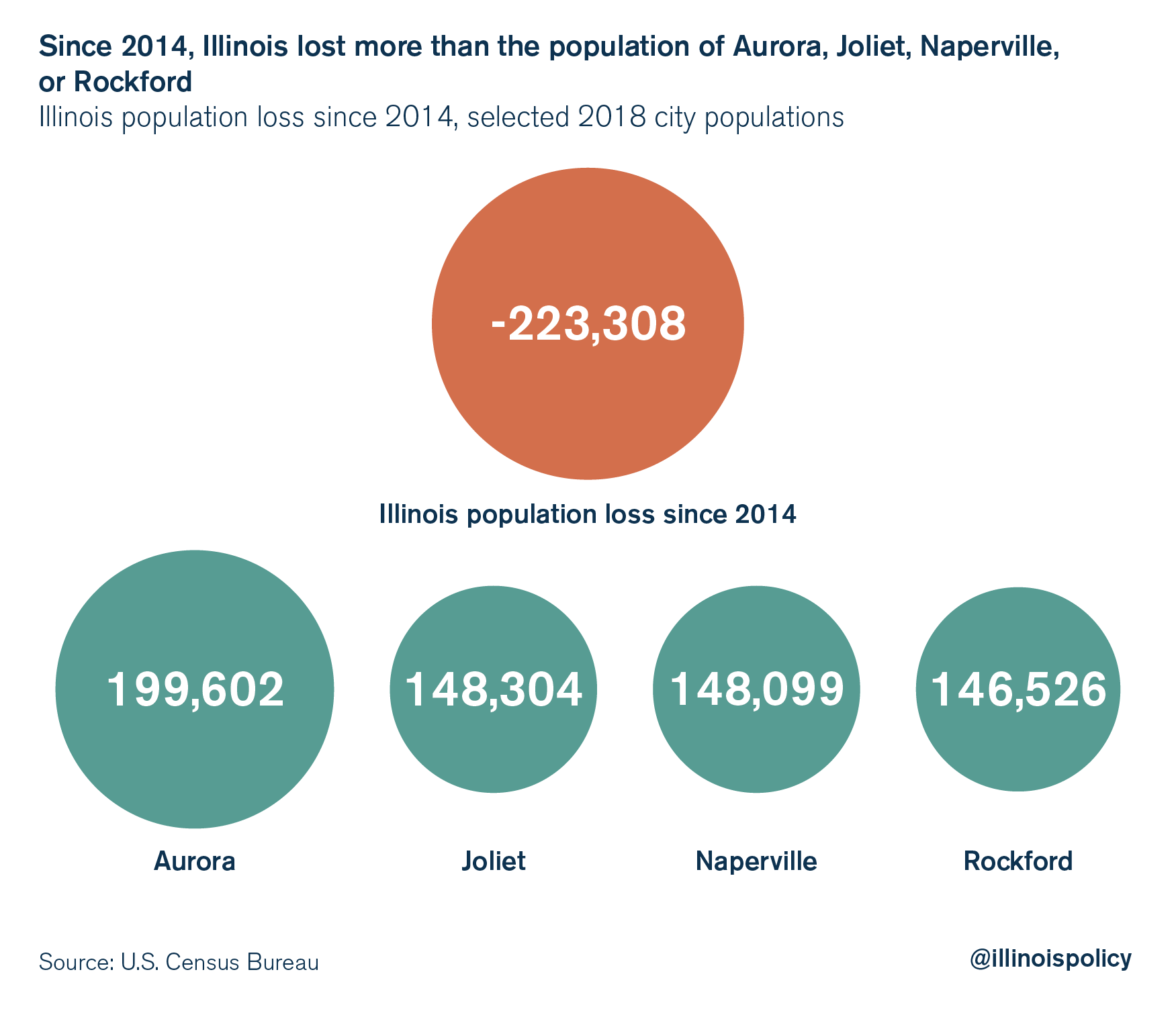

Since Illinois’ population decline began in 2014, the state has shrunk by more than 223,000 people. That’s equivalent to losing the entire city of Aurora, Illinois’ second-largest city.

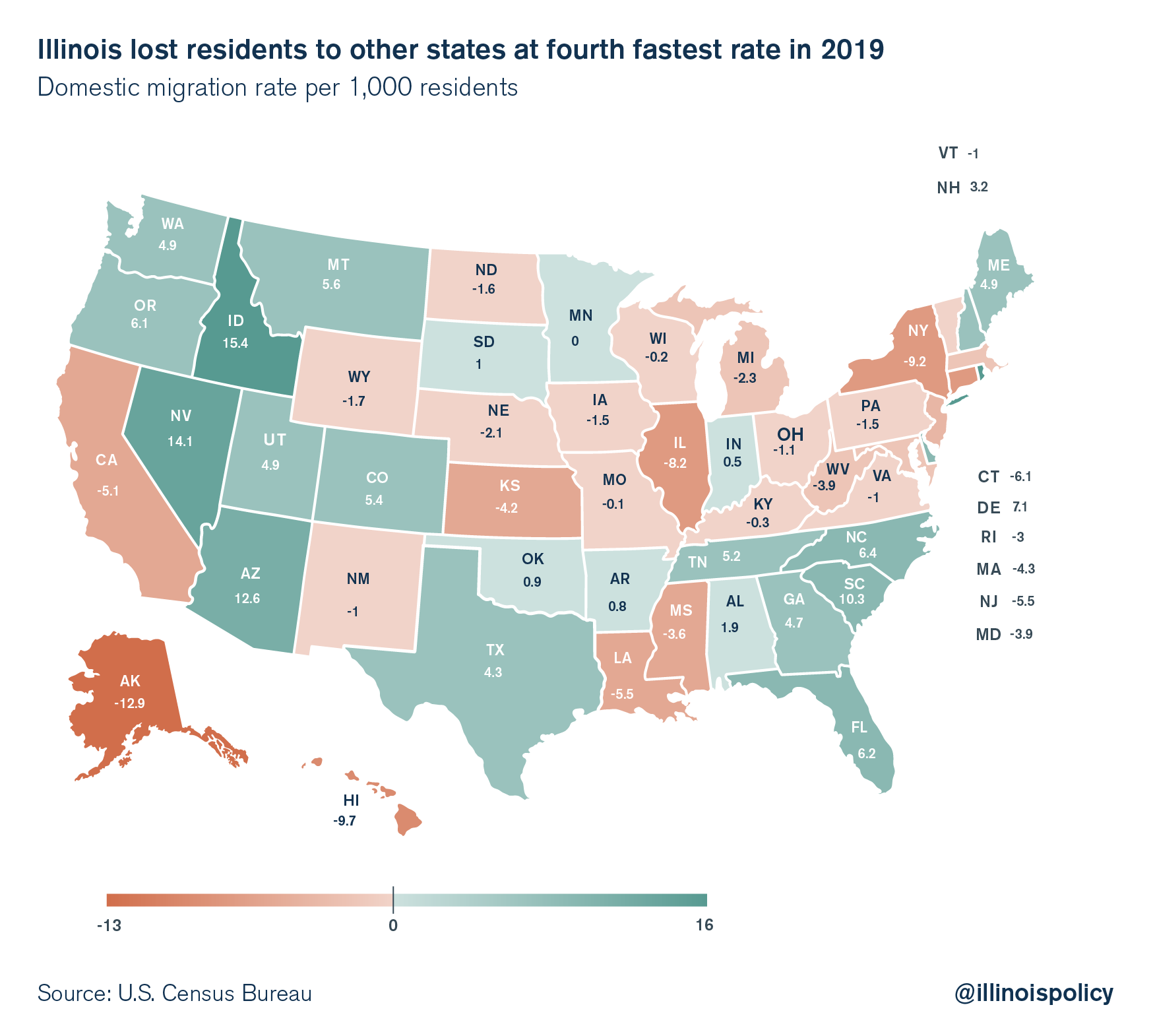

Unfortunately, Illinois’ population decline was the result of losing residents to other states at the fourth-fastest rate this year.

From 2010-2019, Illinois lost 852,544 residents to other states on net. As a share of each state’s population, that was the third-fastest rate of outmigration in the nation, behind Alaska and New York.

Prior analysis has revealed that the largest segment of Illinoisans leaving the state are prime working-age individuals. While those leaving the state are obviously doing so to seek greener pastures, it is important to consider what population decline and outmigration mean for those who remain.

Effects of population decline on those who stay

A poll conducted late last year by NPR Illinois and the University of Illinois Springfield revealed the No. 1 reason Illinois say they want to leave is taxes. However, taxes become a growing concern for Illinoisans who stay with each person who leaves.

Population decline, and more specifically the decline in the prime working-age labor force, has serious negative implications for the state’s economy and the growth in state tax revenue needed to pay for current liabilities. As the population shrinks, so too does the potential tax base. Unfortunately, many of Illinois’ costs, such as pension liabilities, are fixed costs that exist independently of population trends, meaning that despite fewer taxpayers, the size of many liabilities won’t shrink.

If Illinois had kept pace with average state population growth since the start of the Great Recession, it would generate $3.45 billion more in state tax revenue annually.

That’s more than the $3.4 billion in new revenue Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s controversial graduated state income tax hike is claimed to generate.

If the state had simply grown at the same rate as the national average, the Land of Lincoln would have seen population growth and nearly 1.14 million more residents – 9% more than it has today. This population growth would also be the equivalent of at least an estimated $78 billion in additional economic activity in the state. That’s equivalent to the size of the Bloomington, Carbondale-Marion, Champaign-Urbana, Danville, Decatur, Kankakee, Rockford, and Springfield economies combined.

It would also follow that the state’s General Revenue Funds would have seen a corresponding increase, yielding an estimated $3.45 billion more in state revenue than the state brought in during fiscal year 2019.

Unfortunately, lawmakers have failed to take steps to make the state a more attractive place for businesses and families to locate. They can still fix the problem by introducing policies that handle Illinois’ high debt, high taxes and a shrinking population.

A reduction in the number of taxpayers without a similar reduction in costs for state government has only meant one thing: higher taxes for those who remain. Without reform to state spending or a practical solution to the state’s massive pension debt, lawmakers will continue to burden Illinoisans with massive tax hikes. The most recent proposal has been the push for scrapping the state’s constitutionally protected flat income tax for a $3.4 billion progressive income tax hike. However, in the eight years since the “temporary” income tax hike of 2011, outmigration has continued and state finances have deteriorated.

The Land of Lincoln is now in even worse fiscal condition and saddled with more debt than ever before. And it is clear that pursuing further tax hikes won’t solve Illinois’ problems. Making matters even worse is that the revenue projections for a progressive income tax didn’t account for the decline in population that the new census data just revealed, meaning the amount of revenue that has been promised is likely an overstatement.

Instead of pursuing the same tax hike policies that have failed to fix state finances while driving thousands of jobs and opportunities away from the state, likely exacerbating the state’s people problem, Illinois needs real reform.

Reversing the trend

In order to reverse population decline, Illinois needs to attract and retain more residents. However, despite high taxes being the No. 1 reason Illinoisans want to flee the state, lawmakers are asking Illinoisans to approve a $3.4 billion progressive income tax hike on Nov. 3, 2020.

Removing Illinois’ constitutionally protected flat income tax would not only hurt the economy and open the door for more tax hikes, but would also likely drive more residents out of Illinois.

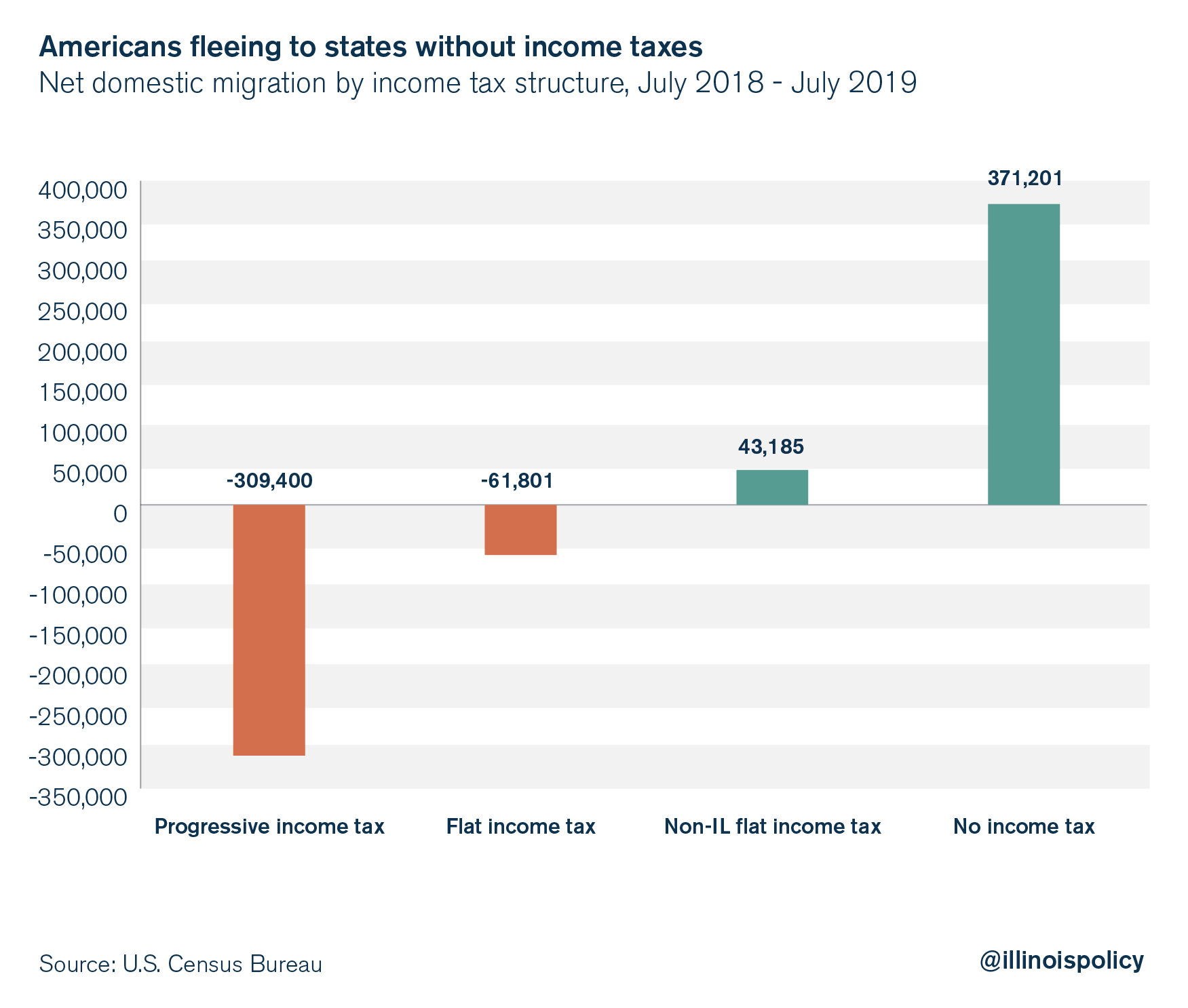

Progressive income tax states are hemorrhaging residents to more competitive tax environments, losing more than 309,000 residents to other states during the past year as a group. Meanwhile, states with no income tax gained more than 371,000 residents. And taken together, flat income tax states excluding Illinois also gained residents from other states.

Instead of again asking taxpayers for more, lawmakers need to pursue real reforms that would put the state on a firm fiscal footing and give much needed certainty and tax relief to families and businesses.

First, Illinois must address its pension problem, which continues to grow despite two record income tax hikes within the past decade. Though pensions take up more than 25% of general fund expenditures, the pension funds are no more solvent. But by amending the Illinois Constitution to allow for the adjustment of the growth rate of not-yet-accrued benefits, the state can reduce pension debt and ensure the plans can continue to support retirees without overwhelming taxpayers. Such changes could include increasing the retirement age for younger workers, tying annual benefit increases to the actual cost of living and making retirement plans more closely resemble 401(k)s for new workers.

Second, a spending cap could help the state meet Illinois’ constitutional balanced budget requirement, which has been ignored for 18 years. One interesting proposal would be a smart spending cap that ties government spending growth to Illinois’ total growth in gross domestic product. Texas and Tennessee have implemented something similar to this, and both have budget surpluses, no state income tax and lower property tax rates than Illinois.

Responsible government spending growth that taxpayers can afford would provide more stability for families and businesses. But if the state substitutes tax hikes for necessary reforms, Illinois can expect to continue seeing population declines as residents find better opportunities elsewhere.