Illinois tax collectors will be busy in 2020, with state government resolved to continue the failed strategy it has pursued for a decade now: take more taxes from state residents without fixing state finances through spending reform.

On Jan. 1, Illinois residents will be subjected to the remainder of the 20 tax and fee hikes approved by Gov. J.B. Pritzker and the General Assembly in the spring. Many of the new ways to take more money from residents have already taken effect in 2019, including doubling the gas tax and increasing the cigarette tax by $1 per pack.

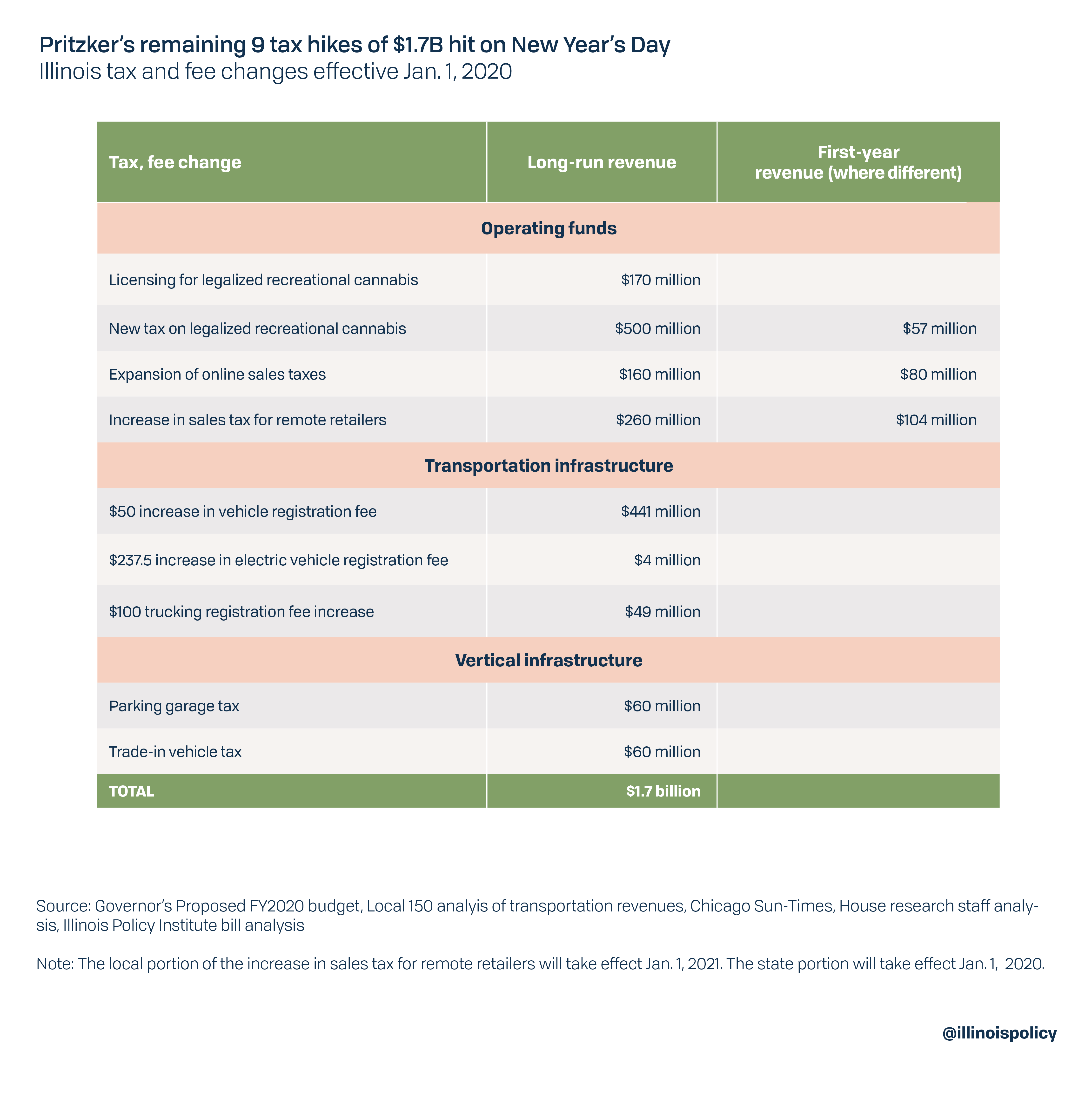

Nine new taxes start Jan. 1, which will collect $1.7 billion a year. Three more taxes are on hold until new gambling operations begin. All told, the 20 tax and fee increases already in place, about to start and lying in wait will take $4.6 billion more out of the economy and taxpayers’ pockets.

Unfortunately, some of the worst tax increases approved by Pritzker hit on Jan. 1. These include new or higher taxes on online purchases and a new form of double taxation on vehicle trade-ins.

The trade-in tax is particularly bad tax policy and cannot be justified as anything other than a revenue grab. The money isn’t even targeted to roads.

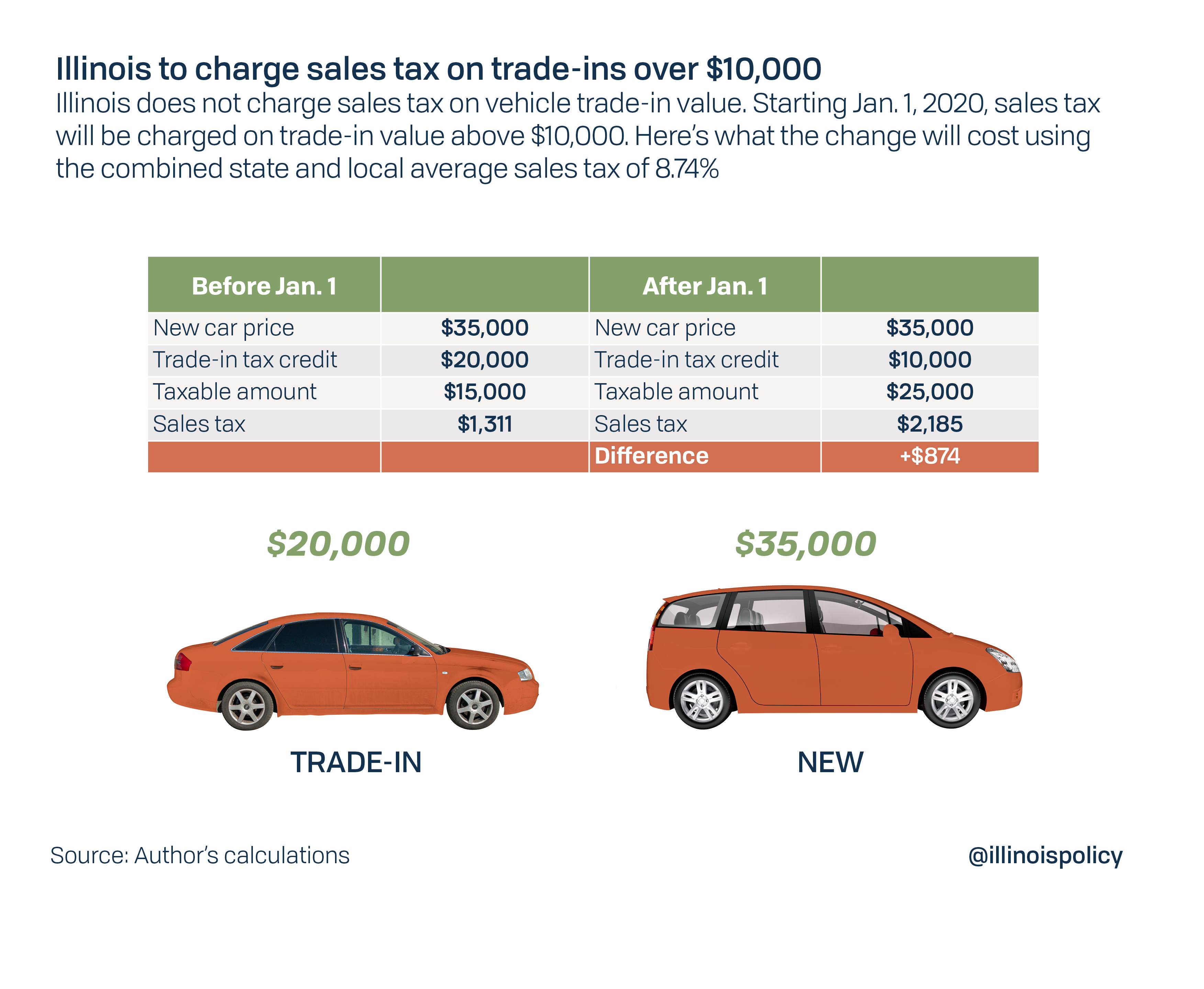

The state currently collects no sales tax on a car’s trade-in value, which acted as credit toward a new vehicle purchase. The sales tax only applies to the difference between trade-in value and the new vehicle’s purchase price, preventing residents from having to pay sales tax first when a vehicle was purchased new and then a second time when it was traded in. After Jan. 1 that trade-in vehicle will be taxed twice.

Any trade-in value above $10,000 will be subject to the full state and local sales tax burden, which is highest in Chicago at 10.25%. The tax is expected to cost Illinoisans $60 million. The state’s auto dealers are rightly upset about the dampening effect this is likely to have on car sales and have called foul on the double taxation aspect.

If you trade in a car valued at $20,000 before Dec. 30 to purchase a $35,000 vehicle, you will pay $1,311 in sales tax, which was only on the value of the new car above the trade-in value. But that exact same transaction will cost you $2,185 after Jan. 1.

If only these higher taxes were going to accomplish something good for state residents, they might be more justifiable. Unfortunately, despite all this new revenue, Illinois Policy Institute analysis has found that the operating budget is as much as $1.3 billion out of balance. Another analysis from the Institute found the $45 billion capital plan, which is partially funded by some of the new taxes, contains at least $1.4 billion worth of waste such as pickleball courts, dog parks and renovations to a decrepit and privately owned theater. The trade-in tax is for those types of projects, not highway construction.

The state’s worst-in-the-nation pension crisis remains entirely unaddressed in the governor’s fiscal plans.

It doesn’t have to be this way. The Illinois Policy Institute has put forth fiscal reforms that would truly fix state finances and protect taxpayers. These include structural pension reform that starts with a constitutional amendment, a spending cap that ensures politicians cannot spend more than taxpayers can afford and a fix to the state’s currently toothless balanced budget requirement.

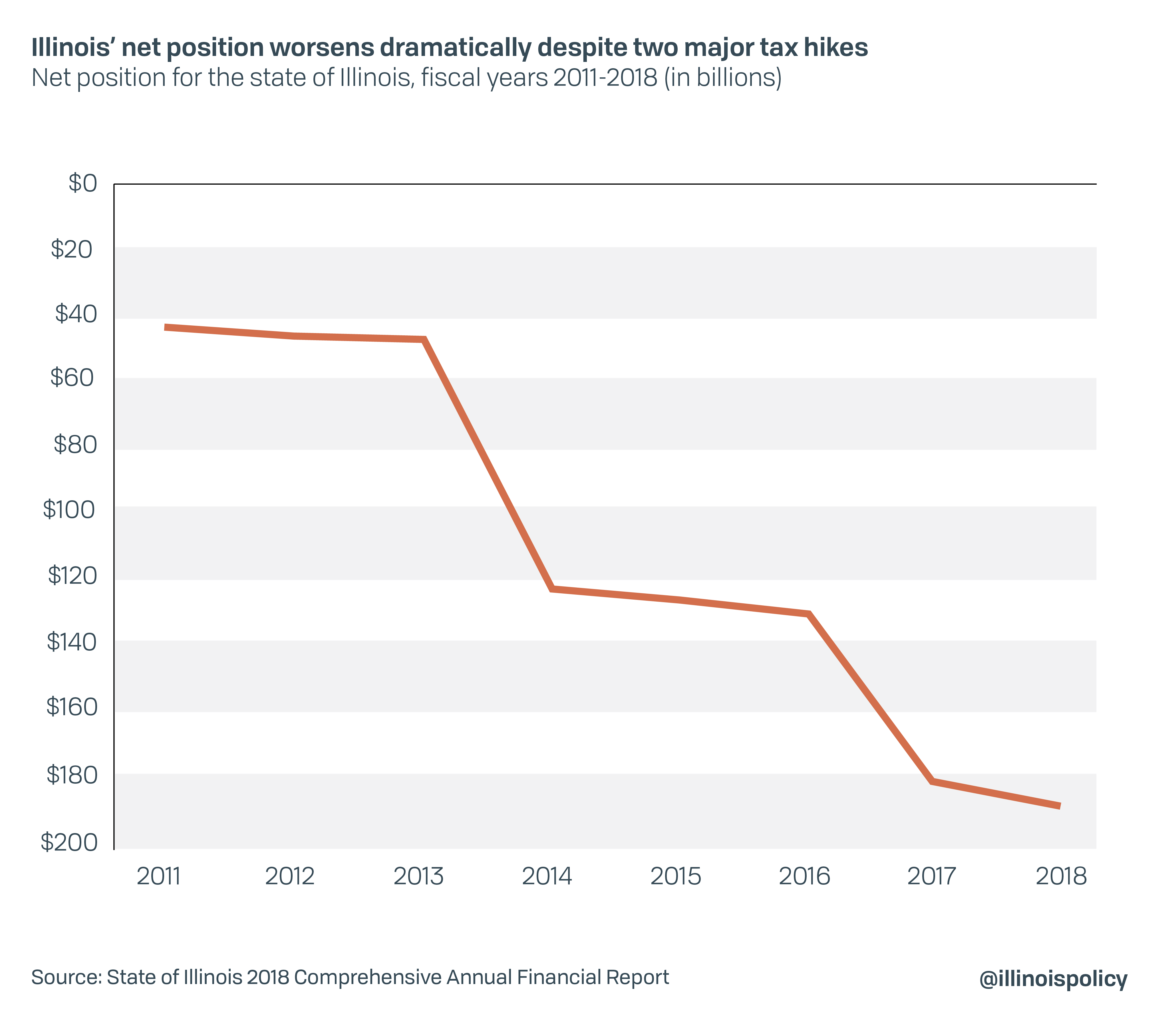

So far, lawmakers have opted to double down on failure. And if anything has been made clear by recent Illinois history, it’s that tax hikes are a failed strategy for fixing the state’s deteriorating finances.

Since the state first attempted to solve its problems with a “temporary” income tax hike in 2011, the net deficit of the state – which is similar to an individual’s net worth, or net debt – has quadrupled to $189.1 billion from $43.6 billion.

That tax hike was made permanent in 2017, but the new revenue hasn’t helped because the state has a spending problem.

Meanwhile, the state’s economy has continued to lag behind national and regional averages, while more and more residents are fleeing to states with lower taxes and more fiscally responsible politicians.

Only New Jersey is home to a worse net position than Illinois. Notably, New Jersey Democratic Senate President Steve Sweeney, who also works as an ironworker union official, in the face of this reality has been traveling the state calling for pension reform and government worker health care reform.

This data proves it’s time for Illinois to make a change. The state could begin fixing its finances by copying policy from other states, such as Arizona on pension reform, the 39 states with strict balanced-budget requirements, or the 27 states with some form of spending cap. Looking around for best practices works in government as well as business.

Instead, Pritzker appears to have looked to copy the worst practices of other states, namely by putting a progressive income tax hike on the ballot in 2020. No state has adopted a progressive income tax since Connecticut in 1996. The results were lower growth in jobs, wages and gross domestic product combined with increases in poverty and persistent budget deficits rivaling those in Illinois.

Elsewhere, voters in Texas and Colorado have voted to make it more difficult for politicians to raise or create income taxes.

Why would Illinois go in the opposite direction, in spite of the data proving this strategy has failed?

Perhaps if voters soundly reject the progressive income tax on Nov. 3, 2020, Illinois politicians will finally get the message that it’s time for a new plan. Lawmakers will have to look to solutions that have succeeded in other states.

After the vote, politicians will have a little less than two months to consider their New Year’s resolution for 2021. How about this: Let’s stop spending more than we can afford and stop asking taxpayers to make up the difference by hiking their taxes year after year.

Illinois’ financial problems are not insurmountable. They simply require lawmakers to have the courage and will to tackle them properly.

Update: Gov. J.B. Pritzker on Dec. 13 signed into law Senate Bill 119, which delays expansion of the local portion of the sales tax for remote retailers to Jan. 1, 2021. This changes the estimated short-run revenue of the tax to $104 million from $130 million, while the long-run revenue estimate remains unchanged. This article has been updated to reflect Pritzker’s signing.