Amid the worst pension crisis in the nation, lawmakers voted in bipartisan fashion to improve pension benefits for downstate police officers and firefighters without performing the necessary financial analysis to estimate the cost. The enhancements to Tier 2 benefits – for employees hired after 2011 – were part of a bill to consolidate the state’s roughly 650 public safety pension funds into just two funds, one each for police and fire.

Gov. J.B Pritzker is expected to sign the legislation.

Lawmakers justified the changes by pointing to potential violations of a provision of federal law known as “safe harbor.” The Internal Revenue Code requires state and local government employees to either receive Social Security or be part of a retirement system that is at least as generous. Failure to comply with IRS rules could result in a significant taxpayer cost if local governments were forced to make retroactive contributions to Social Security, a concern noted by Pritzker’s task force on pension consolidation. However, as pointed out by the Civic Federation, lawmakers never definitively established that a safe harbor violation existed for Tier 2 public safety workers, nor that the changes in this bill were the minimum necessary to bring the plans into compliance.

In other words, lawmakers responded to a problem they had not confirmed existed with changes they had not confirmed would fix the problem, without knowing how much the changes would cost. Elected officials never sought formal guidance from the Internal Revenue Service.

The three changes intended to bring Tier 2 benefits in line with safe harbor restrictions are as follows:

1) Expand survivor benefits. A husband or wife of a deceased police officer or firefighter will now be eligible for two-thirds of the deceased’s accrued pension benefits, regardless of how long the person worked before their death. Previously, employees hired after 2011 needed to work at least 10 years and vest before survivor benefits were available. For Tier 1 public safety workers hired before 2011, surviving spouses were already eligible to receive a portion of the deceased’s pension regardless of how many years of service an employee had.

2) Increase pensionable salary cap. Tier 2 employees are subject to a pensionable salary cap that began at $106,800 and has grown since 2011 at half of inflation or 3% per year, whichever is less. Salaries can grow beyond the cap, but the portion that is used to calculate pension benefits cannot. With the changes in the bill just enacted, the cap would grow at full inflation instead. A legal memo from the Illinois Municipal League had pointed to the pensionable salary cap as a particular area of concern for potential safe harbor violations, because the current salary cap of roughly $115,000 is less than the Social Security wage base of $132,900.

3) Increase final average salary. A Tier 2 public safety employee’s final average salary, which serves as the basis for calculating monthly and annual pension payments at the end of a career, will now be based on the highest four out of the last five years rather than the highest eight of the last 10. The practical effect is that many employees will see a boost in their initial pension check on retirement, which serves as the basis for subsequent annual increases.

No analysis of the benefit increases was performed by a professional actuary, the specialized financial analysts who estimate pension costs. While the governor’s task force publicly stated the enhancements would cost $14 million to $19 million more per year, this number was not backed up by any public data or methodology to justify it. Some Republican lawmakers who voted against the bill raised the lack of a cost estimate during legislative debates, including Sen. Jason Barickman, R-Bloomington.

One concern is that these benefit enhancements were not truly necessary, but were used as a political bargaining chip to convince police and fire unions to support the legislation. As Rich Miller writes in the Chicago Sun-Times, enhancing survivor benefits has been part of the political agenda for police and fire unions since long before consolidation became a topic of discussion.

Consolidation of downstate police and fire pension funds made sense by itself, the Illinois Policy Institute previously stated. By cutting down on duplicative administrative costs and pooling investment assets to get better returns – an important source of income for pension funds – consolidated pension systems are more efficient.

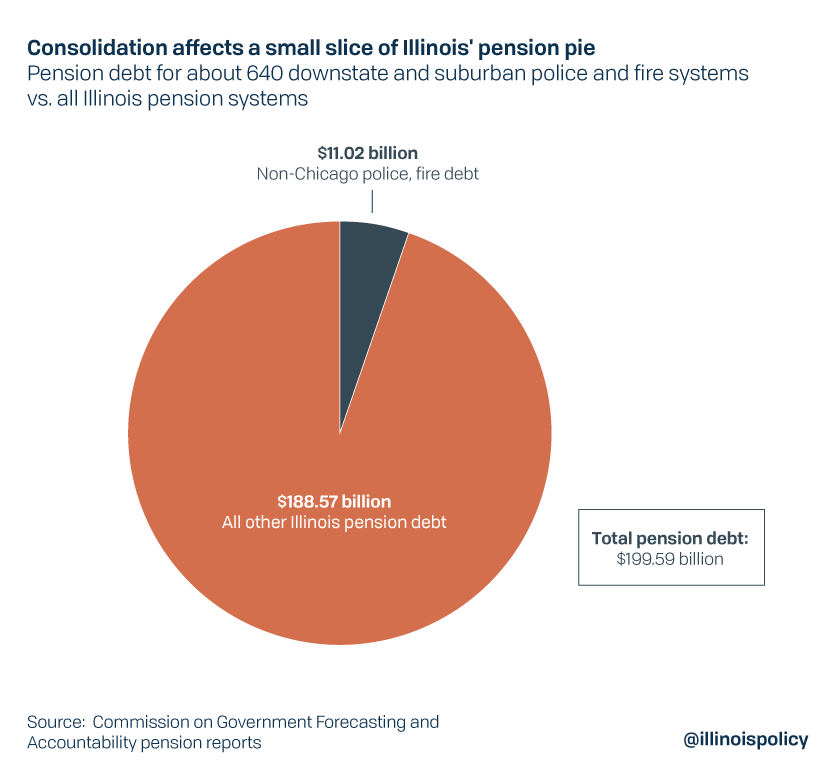

But consolidation is a small step for a tiny portion of Illinois’ pension problem. Total downstate police and fire pension debt is only about 5% of Illinois’ total public pension debt. This plan falls far short of eliminating even the $11 billion of debt held by these plans.

The task force savings estimates of between $160 million and $288 million annually are almost certainly too optimistic. These estimates came from comparisons to existing Illinois pension plans that are more consolidated, but these other plans also have different benefit formulas. Because the existing plans are already better funded, they’re able to diversify their investments more, enabling higher returns.

Ultimately, the combination of unknown costs for the benefit increases and uncertain savings from consolidation means taxpayers should be wary of any potential benefits of this bill. Handing out increased pension benefits without accounting for or offsetting the long-term cost is largely how Illinois got into its pension crisis to begin with.

Pritzker is certainly overselling the benefits, calling the move a “huge bipartisan step,” which is concerning given Illinois politicians’ long history of ignoring the root cause of the pension crisis. Taxpayers must not allow Springfield to pretend they’ve solved the pension problem.

The only real way to fix the pension crisis once and for all – and strike a balance between protecting taxpayers, retirees and vulnerable Illinoisans who rely on government services – is with a constitutional amendment to allow for structural pension reform.