One year ago, the Illinois General Assembly passed a 32 percent income tax hike. Standing as the largest permanent income tax hike in state history, lawmakers hiked the personal income tax to 4.95 percent from 3.75 percent and the corporate income tax to 7 percent from 5.25 percent.

The tax increase not only meant that Illinois families saw less money in their pockets this year, they also experienced a weaker jobs market.

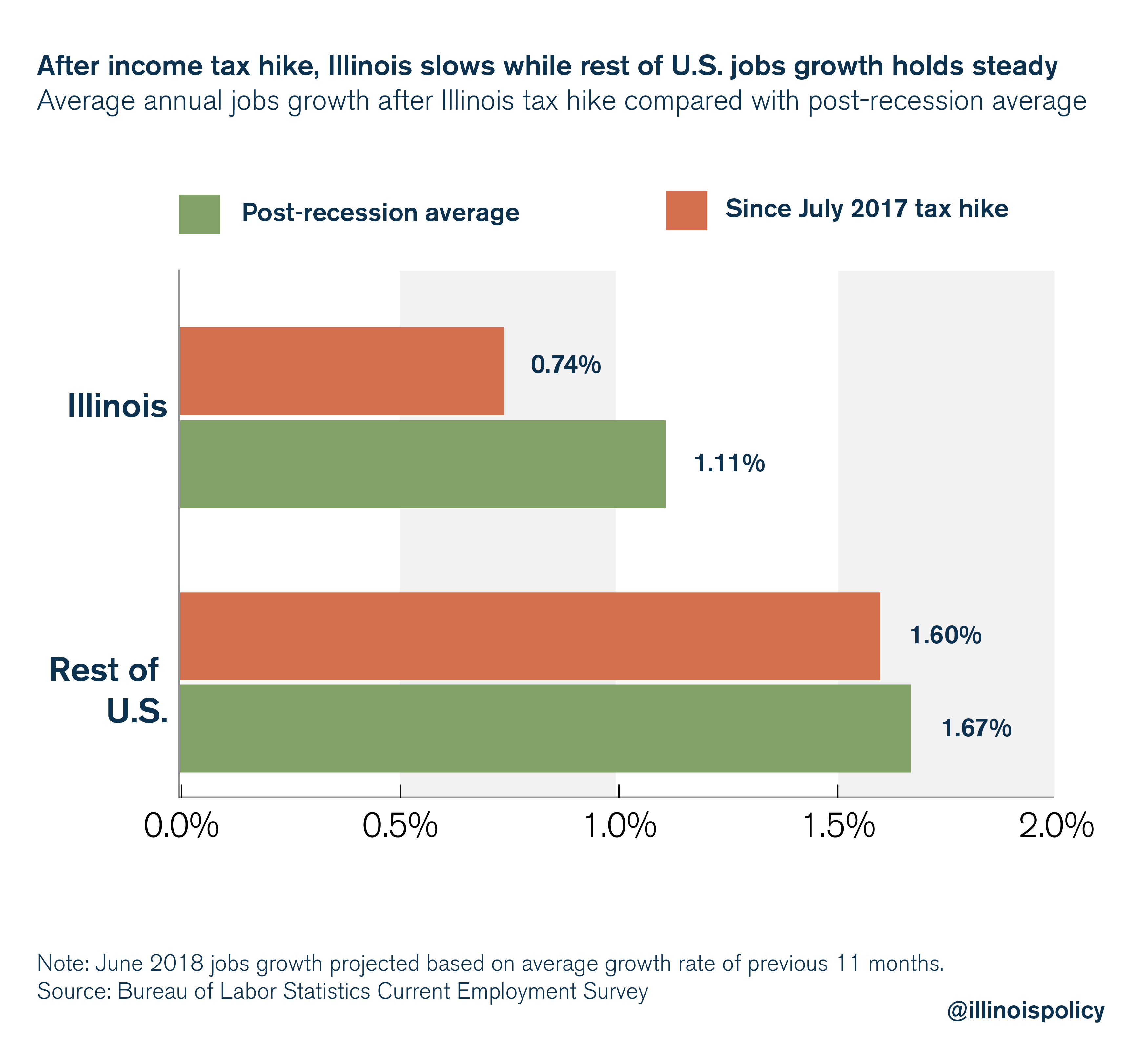

Since the end of the Great Recession, Illinois has seen average annual jobs growth of 1.11 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But in the year since the income tax hike, Illinois’ employment growth was just 0.74 percent, a 34 percent decline.

Meanwhile, jobs growth in the rest of the U.S. remained virtually unchanged relative to its post-recession trend.

A weak jobs market means wages in Illinois will continue to grow slower in Illinois than in the rest of the country.

Beyond jobs growth, Illinoisans saw a concerning change in unemployment trends as well. For the remainder of 2017 after the income tax hike, Illinoisans found themselves unemployed 20 percent longer – 12 weeks from July to December compared with 10 weeks from January to June, according data from the U.S. Census Bureau. For the rest of the U.S., unemployment duration remained unchanged at 9 weeks throughout the year.

Expert literature: Tax hikes harm economic growth

Illinois lawmakers need to learn that hiking taxes on families and businesses is not simply a political action, it’s an economic policy decision that has serious negative consequences for job creation and living standards. There is a large body of expert literature that addresses the effects of tax hikes on economic growth.

Romer and Romer (2010) find that tax increases have a negative impact on real gross domestic product. This is because tax increases have a large and sustained negative impact on investment. These results are consistent with the findings of Blanchard and Perotti (2002) and Mountford and Uhlig (2009).

The expert literature also demonstrates how taxation influences labor market outcomes. Pissarides (1998) finds that a 10 percent cut in taxes levied on employers can reduce unemployment by up to 1 percentage point, while also increasing wages by about 3 percent. Berger and Everaert (2010) also suggest that reducing labor taxes to fight high unemployment may be useful in countries with strong unions.

Divergence: Illinois vs. the rest of the nation

Although the rest of the nation has enjoyed faster economic growth since the end of the recession, Illinois’ underperformance means the gap between the Prairie State and the rest of the U.S. grew more than expected.

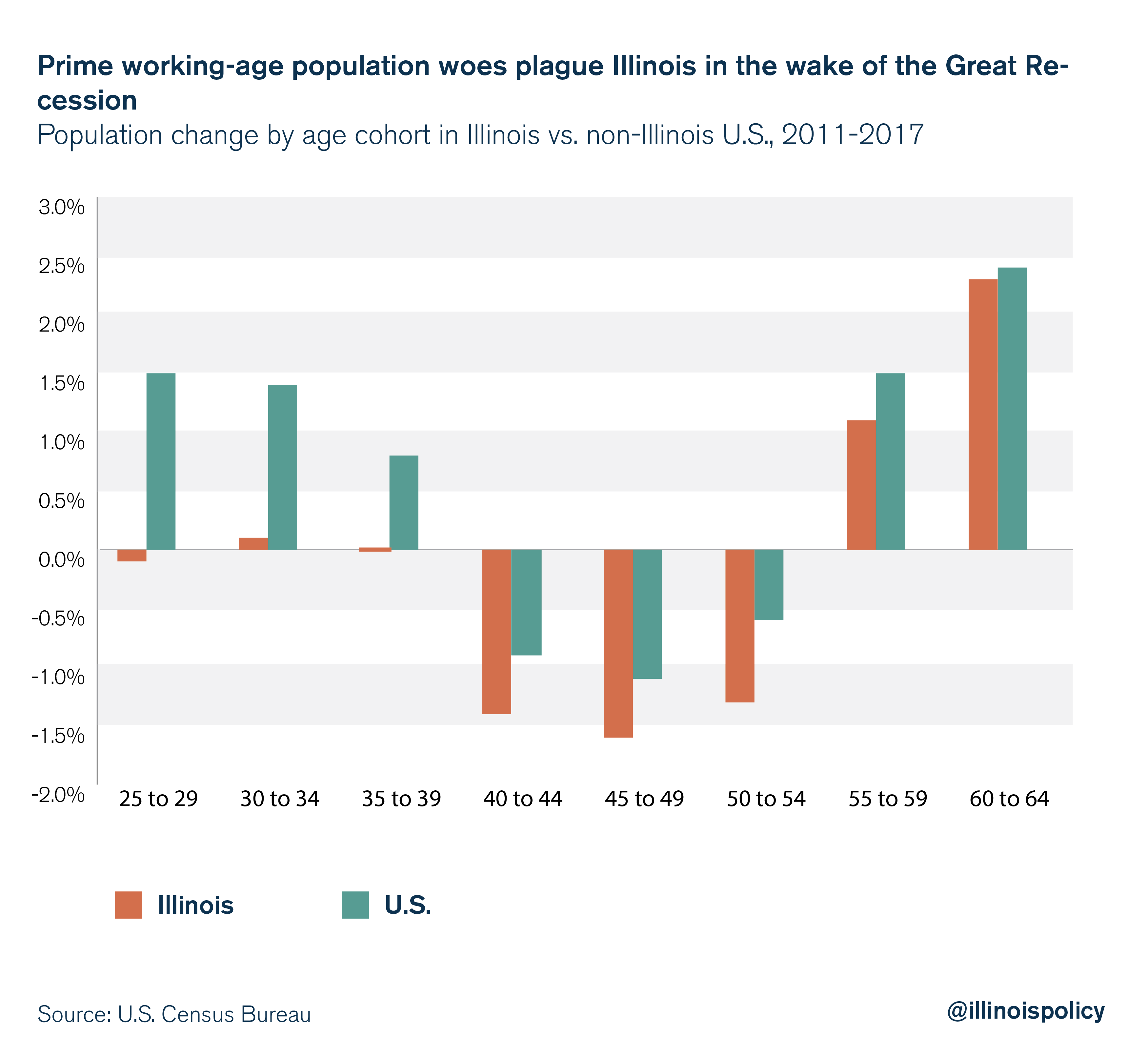

One reason why Illinois’ employment growth will be even further hindered in 2018 is that the prime working-age population is shrinking in Illinois.

Census data reveal that in the wake of the Great Recession, Illinois’ prime working-age population has declined 5 percent while the U.S. prime working-age population has grown 1.4 percent. Over this timeframe, Illinois saw weaker growth in every prime working-age population cohort. The most severe divergence was in ages 25 to 29, which grew 1.5 percent nationally but shrunk in Illinois.

Illinois has seen four consecutive years of population decline, driven by far more people moving out of the state than moving in. And the main culprit behind Illinois’ population decline is not retirees moving away, but rather working-age people seeking greener pastures. The tax hike can be expected to encourage even more working-age Illinoisans to flee the state.

Another reason Illinois could fall further behind is that federal tax reform is expected to allow most Americans – especially those who live in states with low state and local taxes – to keep more of their income. According to the most recently available data – fiscal year 2015, when Illinois’ income tax rate was almost identical to its current rate – Illinois has the eighth highest state and local tax burden in the nation. The fact that low tax states will begin to benefit from the sweeping federal tax changes means the gap between Illinois and the rest of the country will increase, further making Illinois less attractive relative to other states.

Despite additional revenue, Illinois’ fiscal condition remains dire

The 2017 income tax hike aimed to raise an additional $5 billion in revenue in order to fix the state’s budget woes. However, the 2018 budget ended the year with a $590 million deficit and the 2019 budget is up to $1.5 billion out of balance.

Furthermore, all major credit rating agencies have agreed that neither budget since the tax hike has done anything to address the largest drivers of the state’s poor credit rating: pensions and the bill backlog. Illinois’ credit rating remains the lowest in the nation.

Finally, despite having $5 billion in additional income tax revenues, the state took on more debt to pay some of its backlog of bills, kicking the can even further down the road on the $7 billion bill backlog that remains.

Turning things around

There were some positive signs for taxpayers in the year following the income tax hike. Chief among them was that the 100th General Assembly showed bipartisan support for a constitutional spending cap.

Although the spending cap never made it to a vote, members of the House and Senate have pledged to reintroduce the legislation next year. The spending cap would have tied the growth in state spending to the long-run average growth in the economy, avoiding the need for future tax hikes.

In another positive sign for taxpayers, a progressive tax constitutional amendment was thwarted by bipartisan opposition in the House.

However, 61 House members later went on to pass a nonbinding resolution, filed by House Speaker Michael Madigan, endorsing a progressive income tax.

With a potential budget shortfall looming, taxpayers will need to be even more vigilant in assuring the constitutionally protected flat income tax is not overturned. One way to do this is to keep pushing lawmakers to do what Illinois families do every day: spend within their means.