For most Illinois homeowners, it’s become painfully obvious that they pay some of the highest property taxes in the country. But a couple of new studies could lead some to believe the burden might not be that bad, and might even be getting better.

Should Illinoisans take heart? Has the property tax pain subsided?

Unfortunately, no.

Government data show average property taxes paid in Illinois grew more than 6 times faster than household incomes from 2008-2015. And more recently, those property tax bills have risen as returns to investment in home equity have declined in Illinois – meaning property taxes are too often sucking away the savings of middle class families.

A January report by the Civic Federation makes the case that increasing property values caused effective property tax rates to decline in communities surrounding Chicago from 2014 to 2015. And the Cook County Assessor’s Office cited a 2017 study by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and the Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence in stating that Illinois’ property tax system lowers the relative tax burden of low-income families in Chicago. Further, the assessor’s office claimed Chicagoans face lower effective rates than homeowners in many other American cities.

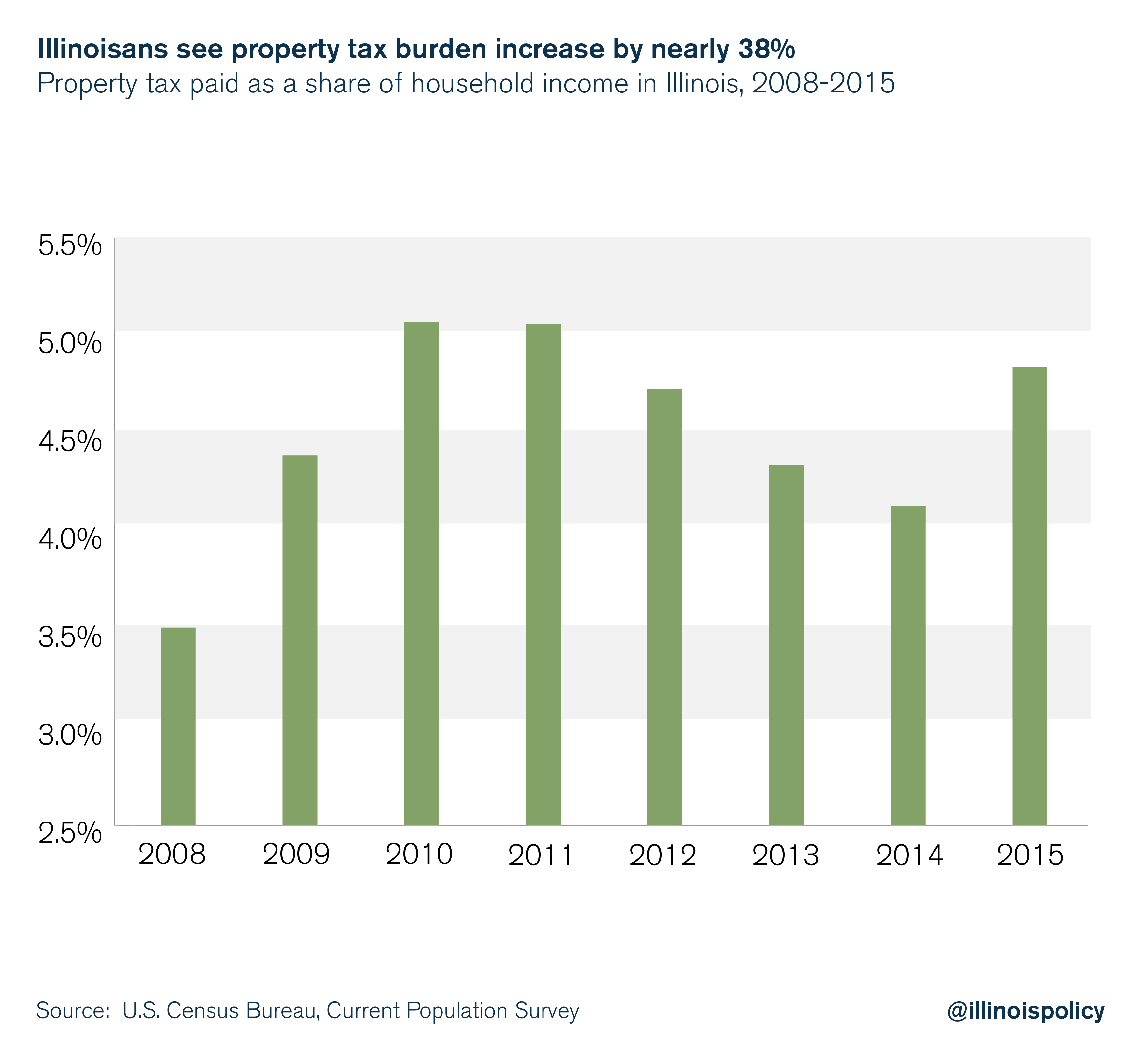

But effective property tax rates don’t reveal the true pain of property taxes for Illinois families. That’s because even if those rates go down, Illinoisans can still see a larger and larger share of their incomes eaten up by property taxes.

And that’s exactly what’s happening. Illinoisans’ real property tax burden – property taxes as a share of income – jumped nearly 38 percent from 2008-2015.

The facts are clear: Property taxes are stretching the budgets of Illinois families and diminishing their ability to prosper.

Illinoisans see higher property tax bills, burden

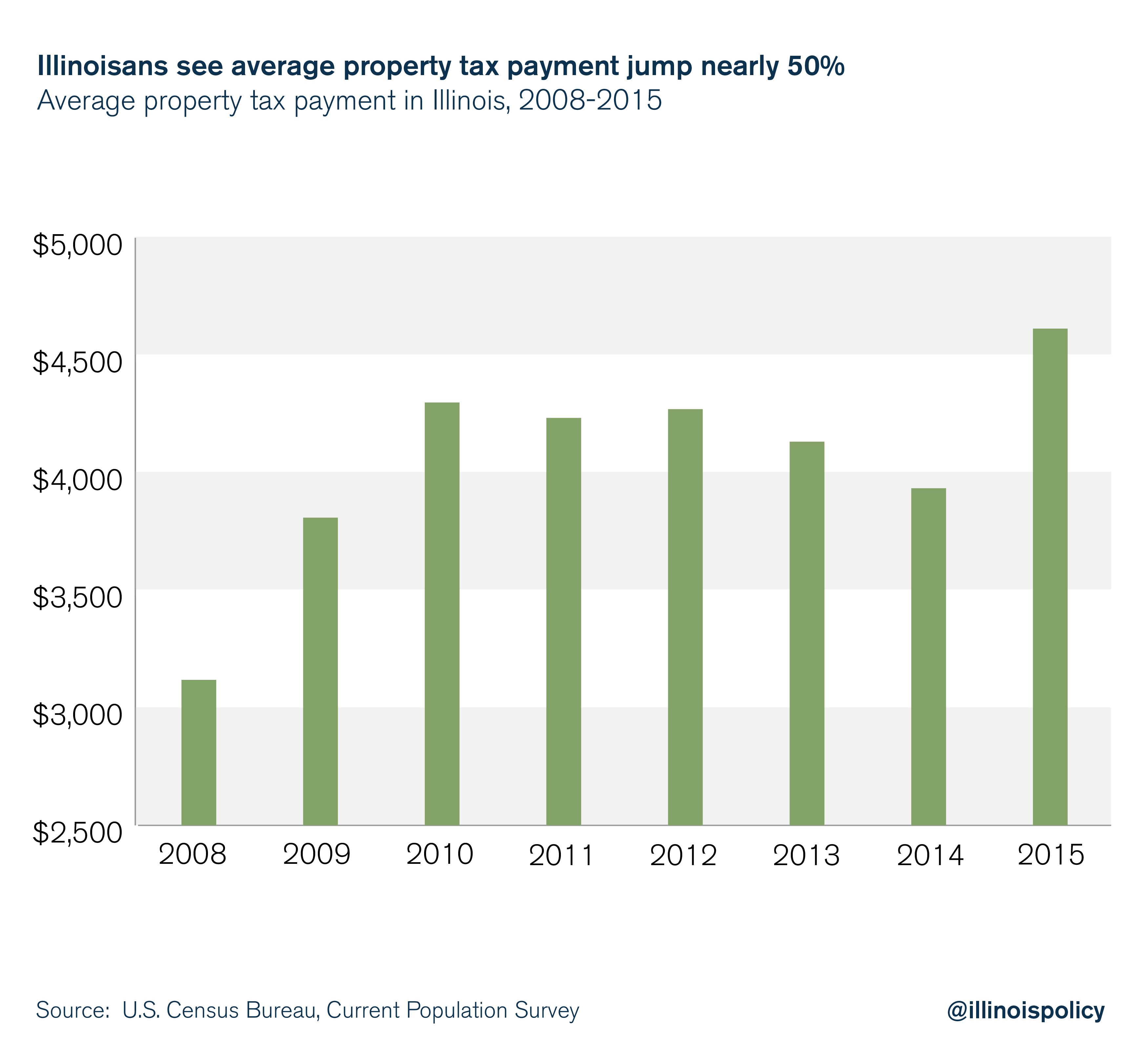

Over the recession era (2008-2015), average property taxes paid in Illinois grew by nearly 48 percent, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, or CPS. From 2014 to 2015 alone, average property taxes increased 17 percent.

But average household income increased by only 7 percent from 2008-2015, according to the CPS. In other words, property taxes grew more than six times faster than household incomes in Illinois.

This means property taxes are taking up a larger share of income, squeezing the household budgets of Illinois families.

The real property tax burden – the percentage of household income paid in property taxes – increased by nearly 38 percent from 2008-2015. Since Illinoisans’ average household income did not grow in 2015, the real tax burden increased by 17 percent from 2014 to 2015 alone.

Property taxes sapping savings

Home equity is one of the main vehicles by which middle class families save for retirement. But in Illinois, those savings are being sapped as property taxes keep marching upward.

The U.S. Census Bureau’s CPS also provides an estimate of the value of investing in home equity.1 For most people buying a home, they expect the value of that investment to increase over time. But if this “return to home equity” measure declines, it means families’ savings are vanishing before their eyes.

According to the CPS, the average return on investment in home equity increased 14 percent over the recession era in Illinois. But from 2014 to 2015, the return to home equity decreased by 2.4 percent.

A key reason for the decline in the return on investment in home equity that year is higher property taxes. This is concerning because it means that even in a time of increasing home equity, homeowners can still see the return on their investment in their homes diminish if property taxes rise high enough.

Why the effective tax rate doesn’t show the whole picture

Illinoisans should be careful not to read too much into studies showing a low or declining effective tax rate for property owners.

The effective property tax rate is the percentage of a property’s value – either its assessed value or in some cases its estimated market value – paid in property taxes during a given year.

Under an effective tax rate calculation, if the magnitude of a property tax increase is smaller than an increase in the property value, then the effective tax rate decreases.

But this calculation has some important limitations.

First, a calculation using properties’ assessed value uses information on the median level of assessment within a given geographical area. However, this property value assessment is highly subjective and prone to mistakes. A recent study by ProPublica Illinois and the Chicago Tribune accused Cook County Assessor Joseph Berrios of failing taxpayers by producing valuations for thousands of commercial and industrial properties in Chicago that did not change at all from one reassessment to the next.

Even aside from the egregious example of the Cook County Assessor’s Office, problems inherent generally in property value assessments mean Illinoisans have reason to be skeptical of assessed value as a reliable way to measure changes in the property tax burden.

Second, a good measure of a given tax burden should reflect how much a tax constrains a household’s budget and distorts economic decisions. The effective tax rate doesn’t completely capture that reality. This is why even studies that calculate the effective tax rate based on a property’s market value – not its assessed value – still can’t fully describe the burden shouldered by Illinois families.

The real property tax burden should account for the effect of property taxes on monthly housing costs, directly affecting a household’s ability to prosper.

For those reasons, researchers can use data from the Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey to investigate: How much of a household’s income is used to pay property taxes in Illinois?

The CPS is one of the oldest, largest and most well-recognized surveys produced by the U.S. Census Bureau, covering 1962 to the present. Data include individuals’ responses about demographic information, employment, program participation and supplemental data on topics such as taxes paid, voter registration, food security and more.

Property tax payments are only available up to the year 2015. Over the recession era (2008-2015), average property taxes paid grew 6.6 times faster than household income in Illinois.

Illinoisans need solutions, security

Surging property tax burdens as Illinois loses people to other states in record numbers is a toxic mix. Indeed, local governments across the state continue to hike property taxes while the state is shrinking.

The General Assembly should take immediate action to address rising property tax burdens for Illinois families.

Passing a property tax freeze on homeowners’ actual bills (not just the levies of local governments) and requiring voter approval for property tax hikes are two powerful reforms that would go a long way for Illinois families dealing with stagnant incomes.

To be clear: A property tax freeze should only be a first step – freezing taxes at their current unaffordable rate is not a permanent solution. The permanent solution is to reduce property taxes and return financial security to Illinois families.

After giving families greater security in their homes through a property tax freeze, lawmakers must act to rein in the cost drivers that push those bills higher and higher, thus reducing property tax burdens.

First, leaders must move to consolidate scores of Illinois governments. The Land of Lincoln is home to more units of local government than any other state, by far. That drives up property taxes. A great place to start is in Illinois’ duplicative school district administrations.

Furthermore, addressing the stacked deck of government union negotiations is a crucial step in providing long-term stability for homeowners. Unlike in every neighboring state, government worker unions in Illinois currently have the power to hold taxpayers over a barrel, which results in unaffordable contracts. It’s no wonder residents are stuck paying some of the nation’s highest property taxes.

Illinoisans deserve security in their homes when planting roots in the state. But growing property tax burdens are robbing them of that security.

Endnotes

- The CPS home equity calculation is constructed as follows: First, only dwellings in the CPS where the householder is the owner are included. Second, using the common variables of householder’s age, number of people in the household, total household income and location variables (i.e., statistical area, state, central city indicator or region), a survey respondent record from the American Housing Survey is matched with each CPS homeowner. Once the match is made, the CPS dwelling is appended to include home values, land values, property taxes and housing debt from the survey respondent record. The home equity is calculated by taking the reported value of the property and subtracting the remaining home debt. The final value of “return to home equity” is then calculated by multiplying home equity by the annual Standard & Poor’s high-grade municipal bond yield and subtracting property taxes.