Skyrocketing property tax bills are forcing Illinoisans from their homes. Since 1990, residential property taxes have grown more than three times faster than median household incomes in the state. Illinoisans now pay some of the highest property taxes in the nation.

One contributing factor to those higher taxes: government unions’ power to strike.

Illinois has some of the most restrictive laws in the region when it comes to negotiating with government worker unions. That, in turn, drives up the cost of operating government. And that cost is passed on to taxpayers.

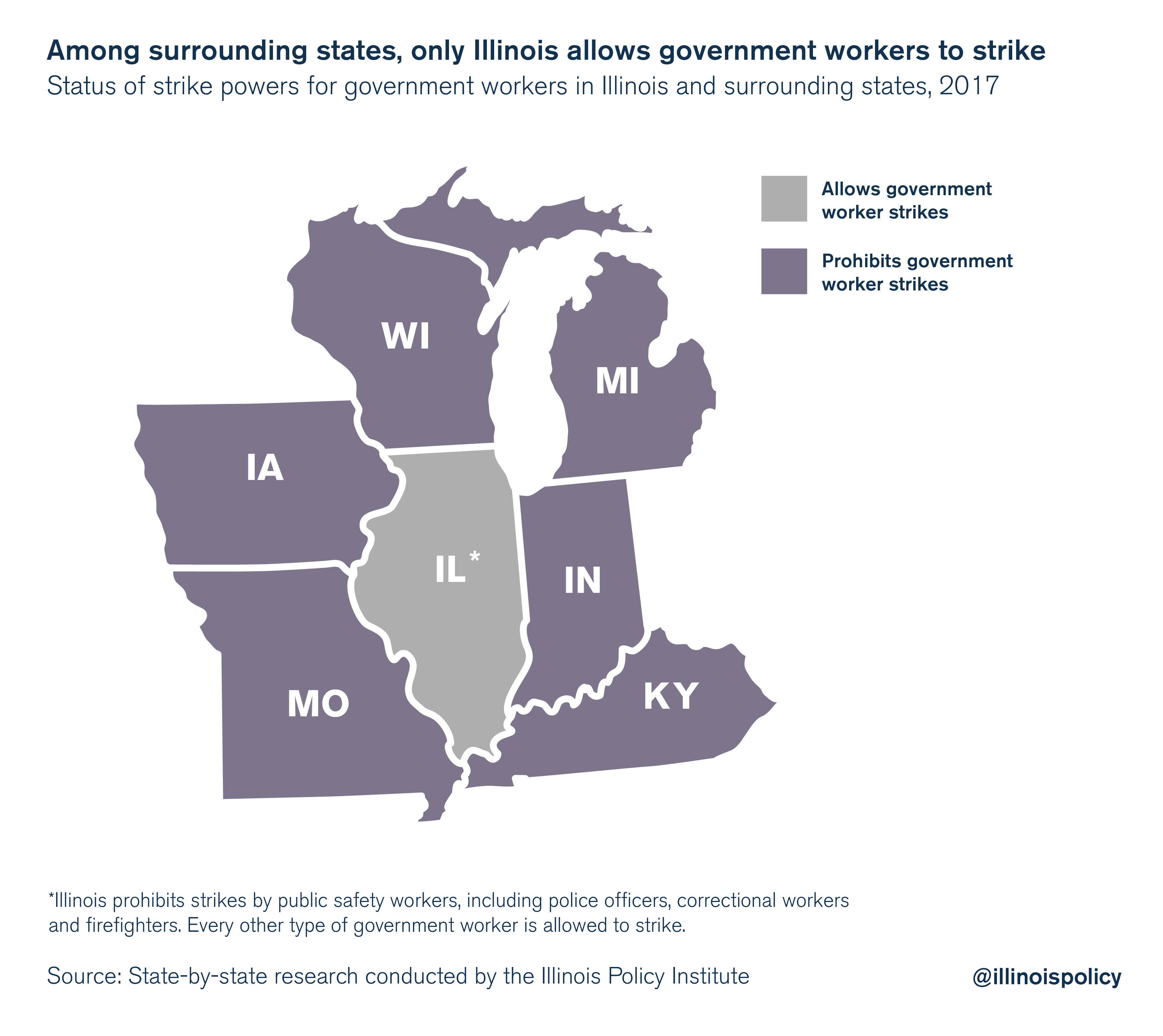

One of the most glaring differences between Illinois and its neighbors is Illinois alone gives government worker unions the power to strike. That grants those unions the ability to shut down government services and schools.

It’s a power unions use to get what they want – and it drives up costs.

The right to strike stacks the deck against taxpayers

Ignoring the advice of early union leaders not to allow the unionization of government workers, Illinois enacted the Illinois Public Labor Relations Act and the Illinois Educational Labor Relations Act in 1983. Together, those laws grant state and local government employees and teachers the power to go on strike.

In Illinois, public safety workers cannot strike. But every other type of government worker can.

But that’s not the case with Illinois’ neighboring states. All public sector workers and their unions are prohibited from going on strike in every one of Illinois’ surrounding states. That includes everyone from clerical workers at a local town hall, to teachers, to state workers and police.

Those prohibitions restore the balance of power between those who work for government and those who do not.

The ability to strike is a powerful tool. When a government worker union in Illinois doesn’t get its way in negotiations, it can threaten to shut down state and local governments or schools – and the services residents need – in order to have its demands met.

The power to strike is not merely theoretical. It plays out across the state in multiple ways every year:

- In May 2017, faculty at the University of Illinois-Springfield walked out on students just one week before finals.

- In February 2017, Illinois’ largest government worker union – representing 35,000 state workers across the state – authorized a strike if Gov. Bruce Rauner attempted to implement a contract the union didn’t like.

- In September 2016, teachers in Champaign voted in favor of a strike after students were already in school for the year.

- Since 2012, the Chicago Teachers Union has gone on strike – or threatened to go on strike – at least four times.

For example, when CTU went on strike in 2012, Chicago Public Schools was already facing a $1 billion budget deficit and an $8 billion teacher pension shortfall. But CTU went on strike anyway, demanding higher wages even though CTU members already received high salaries and generous benefits. In fact, Chicago teachers are some of the highest-paid among the nation’s 50 largest school districts.

After the strike ended, CPS announced it had to close 50 schools and lay off thousands of teachers to help reduce costs. That eventually led to property tax hikes to fund schools.

And look at the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. In the midst of Illinois’ financial crisis, AFSCME is adamant that the state spend an additional $3 billion in increased wages and benefits – including payroll increases up to 29 percent over the course of the contract. It isn’t enough that state workers in Illinois are already the highest-paid state workers in the nation when adjusted for cost of living. Union leaders want more, and they are willing to go on strike – and risk the well-being of Illinoisans – to have those demands met.

In all, Illinois’ restrictive collective bargaining laws – including the right to strike – have inflated state and local government spending by $4 to $9 billion in 2014 alone.

Restoring fairness in negotiations

Government unions in Illinois’ neighboring states cannot make exorbitant demands – such as those Illinoisans have seen – while threatening to walk out if those demands are not met. In turn, those prohibitions help protect residents from the taxes that accompany outlandish union demands.

And Illinois’ neighbors don’t just prohibit strikes. They also dole out significant punishments for unions that break the law.

A government worker union in Iowa that fails to abide by the state’s strike provisions can be decertified – i.e., prevented from representing the workers – for at least 12 months.

In Indiana, a police or fire union that engages in a strike loses the right to represent employees for at least 10 years.

Examples of illegal strikes followed by such union decertification penalties are few and far between. Arguably, that’s because the states’ strike prohibitions keep government worker union actions in check. Those unions know they risk losing their foothold if they utilize an illegal strike.

These are provisions that place the well-being of residents who do not work in the public sector as a priority in the eyes of the government.

What might it look like if Illinois followed the lead of neighboring states? For one, unions such as CTU could not walk out on parents and students without facing repercussions.

And if unions did decide to strike – like CTU’s illegal one-day strike in April 2016 – it would result in the union being decertified.

Such a law would act as a check on aggressive union behavior that has driven up property taxes, resulted in teacher layoffs and school closings, and left students without a place to go during the school day.

With the strike threat as an ever-present “negotiating” tool, it’s no wonder government unions have driven up the cost of running the state. The deck is stacked against the vast majority of Illinois residents who don’t take a public sector paycheck.