The Illinois House of Representatives voted March 7 to divert up to an additional $314 million in state tax dollars each year to local governments.

This proposal, House Bill 278, would increase state spending despite Illinois’ billions of dollars in deficit spending, billions more in unpaid bills, over $130 billion in pension debt, and dismal credit rating. The bill also props up a system that encourages local government overspending and a lack of accountability.

After passing 67-47 in the Illinois House of Representatives, HB 278 heads to the Illinois Senate for consideration.

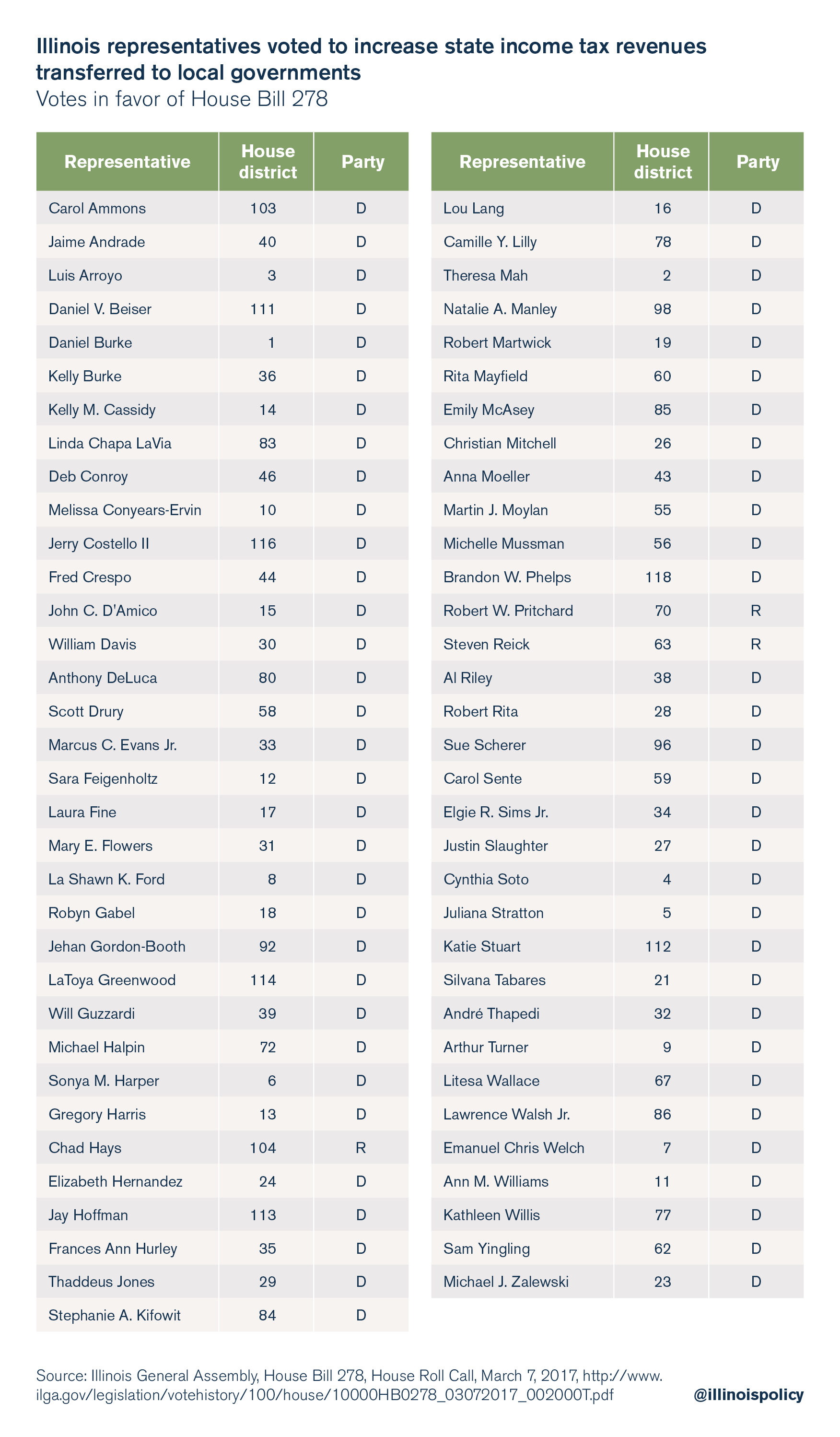

Sixty-four Democrats and three Republicans voted in favor of HB 278:

Carol Ammons, Jaime Andrade, Luis Arroyo, Daniel V. Beiser, Daniel Burke, Kelly Burke, Kelly M. Cassidy, Linda Chapa LaVia, Deb Conroy, Melissa Conyears-Ervin, Jerry Costello II, Fred Crespo, John C. D’Amico, William Davis, Anthony DeLuca, Scott Drury, Marcus C. Evans Jr., Sara Feigenholtz, Laura Fine, Mary E. Flowers, La Shawn K. Ford, Robyn Gabel, Jehan Gordon-Booth, LaToya Greenwood, Will Guzzardi, Michael Halpin, Sonya M. Harper, Gregory Harris, Chad Hays, Elizabeth Hernandez, Jay Hoffman, Frances Ann Hurley, Thaddeus Jones, Stephanie A. Kifowit, Lou Lang, Camille Y. Lilly, Theresa Mah, Natalie A. Manley, Robert Martwick, Rita Mayfield, Emily McAsey, Christian Mitchell, Anna Moeller, Martin J. Moylan, Michelle Mussman, Brandon W. Phelps, Robert W. Pritchard, Steven Reick, Al Riley, Robert Rita, Sue Scherer, Carol Sente, Elgie R. Sims Jr., Justin Slaughter, Cynthia Soto, Juliana Stratton, Katie Stuart, Silvana Tabares, André Thapedi, Arthur Turner, Litesa Wallace, Lawrence Walsh Jr., Emanuel Chris Welch, Ann M. Williams, Kathleen Willis, Sam Yingling, Michael J. Zalewski

HB 278 hikes state spending, increasing the burden on Illinois taxpayers

Illinois already spends $8 billion more than it takes in and has a $12 billion unpaid bill backlog and a $130 billion pension crisis. HB 278 will divert up to $314 million more each year in state tax dollars to localities, which will create an even larger hole in the state budget that politicians will look to taxpayers to fill.

Illinois taxpayers just avoided a tax hike worth nearly $7 billion when the Illinois Senate’s so-called “grand bargain” budget deal failed to pass in early March. The Senate’s “grand bargain” tax proposals included: raising individual and corporate income taxes 33 percent, hiking taxes on food, drugs and medical supplies, expanding sales taxes to cover services, and imposing a tax on sugary drinks. Diverting more state tax revenues to localities, however, could tempt politicians to take another swing at a tax hike.

HB 278 props up local government overspending and other bad habits that lead to high property taxes

HB 278 moves state tax dollars around in a shell game that enables fiscal irresponsibility and overspending by local governments.

The bill would raise the percentages of individual and corporate income tax revenues that the state will send to Illinois’ local governments by way of the Local Government Distributive Fund, or LGDF. Through the LGDF, the state funnels income tax dollars to local governments based not on need, but on their pro rata share of the state’s population. The LGDF has $1.3 billion in state income tax collections that it will pay to cities and counties.

HB 278 provides that starting in 2020, 10 percent of net state individual and corporate income tax revenue will go to the LGDF, up from the 8 percent of net individual income taxes and 9.14 percent of net corporate income taxes the LGDF currently takes in. The measure phases in the increase, raising the LGDF’s cut of net individual income taxes to 8.5 percent and its take of net corporate income taxes to 9.355 percent in 2017, and by additional increments each year from 2018 to 2020.

State funding of localities fuels reckless spending on perks and expenses that would otherwise be unaffordable for local governments. And the spending enabled by LGDF dollars is often far costlier than it may first appear. For example, local governments may use LGDF money to hire extra municipal government personnel, or to avoid conflict with government-worker unions by handing out overgenerous salaries and benefits to public employees. If the money comes from the LGDF, local residents may not immediately feel the effects of this spending, and politicians can dole out funds without having to justify it to local taxpayers. But eventually pension costs for those employees end up growing at extraordinary rates. This forces local residents – who already pay some of the highest property taxes in the nation – to pick up the hefty tab and crowds out funding for municipal services such as libraries and road repair.

All Illinoisans lose under HB 278

HB 278 creates an additional $314 million annual burden that Illinois cannot afford.

And just as concerning, it takes the state even farther away from ending the state-local funding shell game that occurs through the LGDF. Rather than increasing funding to the LGDF, lawmakers should put an end to all LGDF distributions to counties and municipalities with populations above 5,000. Requiring local governments to spend within their means, rather than encouraging bloated bureaucracies and expensive perks through state funding, is an important step toward reining in property taxes.

But lawmakers should not stop there. In addition to curbing state subsidies such as the LGDF, lawmakers should take further steps to hold down property taxes by instituting a property tax freeze and ending costly state mandates that drive up local governments’ costs.

And instead of resorting to harmful tax hikes, lawmakers should bring Illinois’ costs under control by: reforming pensions, aligning the cost of state worker compensation with what taxpayers can afford, streamlining Medicaid spending, and reducing excessive bureaucracy and administrative costs in higher education.